Don’t Tax What You Want More Of

Last summer Sarasota County Director of Smart Growth Peter Katz created a buzz with a study showing that on a per-acre basis, downtown mixed-use development typically generates more than 30 times the tax revenue of shopping malls, busting the myth that cash-strapped municipalities ought to bend over backwards to attract mall development.

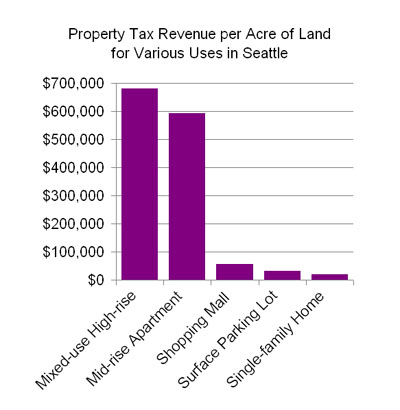

Recently the Downtown Seattle Association did some analogous number crunching on total property tax (including state, county, city, school district, etc) for a range of uses in Seattle, and the results are similarly dramatic, as shown in the chart below.

Per acre of land used, the property tax revenue generated by the mixed-use high-rise (Harbor Steps) is more than ten times that of the shopping mall (University Village), and about 20 times that of a surface parking lot (4th and Washington). The mid-rise apartment (Pickering Place) generates about 10 percent less than the high-rise, while the the single family home (Northeast Seattle) generates the least of all.

There’s a “well, duh!” side to these results, given that property tax is generally based on assessed value. But these gaping differences need to be understood in terms of how they impact choices we make regarding how the city is developed.

First, the data should help dispel the impression some seem to have that high-density mixed-use projects are freeloaders. But more importantly, given the well documented environmental benefits of high-density urban infill development in cities like Seattle, the existing property tax structure is tipping the economic scales in a way that thwarts the kind of development we want. The case of a downtown surface parking lot is a particularly egregious example, because the relatively low tax rate encourages owners to sit on underutilized land, impeding its conversion to more beneficial uses. You tax what you want less of.

There is a relatively straitghtforward fix for this deconstructive market distortion: land value tax (LVT). Just like it sounds, an LVT is a levy on the value of the land alone, and not on the improvements on that land. In practice, such a tax would translate to big rate hikes on underutilized land, and rate cuts on land with high-value improvements. Proponents of LVT argue that, in the words of Wikipedia, “because LVT deters speculative land holding, dilapidated inner city areas are returned to productive use, reducing the pressure to build on undeveloped sites and so reducing urban sprawl.”

In effect, an LVT would work a lot like a tax on low-density development, justifiable as compensation for the externalized environmental costs associated with typical low-density lifestyles. Based on that rationale, former Vancouver, BCÂ mayor Sam Sullivan has recently been advocating for a tax system that would shift the property tax burden from high- to low-density neighbhorhoods.

Of course, no matter how smart and sensible such a tax shift may be, because of the massive shake up to the status quo it would cause, it is not likely to be taken very seriously in most political circles. Because, you know, everything’s just fine and dandy as it is, no need to rock the boat, I mean, it’s not like we’re facing the most dire environmental and resource crises in the history of humanity or anything like that… ahem.