Linkage Fees Will Impede Housing Production

At the heart of the debate over Seattle’s proposed linkage fee is the question of whether it undermines its own intent to provide affordable housing by either raising rents or impeding the production of housing. A recent post by Owen Pickford at The Urbanist argues that a linkage fee would have no negative impact on the housing market, and therefore “urbanists must support it.” This post will explain why that position has no merit.

Other than cases of unique developments that have limited substitutes, a linkage fee will result in a reduction in land values rather than increased rents. So what we need to examine is the effect of depressed land values on the production of housing.

The most widely used metric for predicting whether a piece of property can be redeveloped is the ratio of the value of the improvements on the land, to the value of the land itself. The larger the ratio, the less likely a property will redevelop. Right away we can see that because a linkage fee reduces land value but not improvement value, it skews that ratio towards predicting no redevelopment.

To put a finer point on it:Â Pickford’s position contradicts the standard methodology used by the City of Seattle, King County and countless other municipalities to estimate “buildable land,” that is, land that can be redeveloped. This alone should be enough to cast serious doubt.

Overall, on my assessment Pickford’s argument that a linkage fee would not impede housing production is flawed for two primary reasons: It neglects the role of the property seller and existing uses; and it relies on supporting evidence that is highly tenuous, if not irrelevant.

The Role of the Seller and Existing Uses

Housing production in Seattle almost always involves redevelopment of property that has income-generating existing uses on it. The typical owner of a property that is being considered for redevelopment will evaluate an offer from a buyer based on the net present value of the property (i.e. including income from existing uses), compared to what the cash from the sale could earn if it was put into other investments. Add a linkage fee to this equation and the buyer’s cash offer will be lower, tipping the scales towards holding on to the existing income-generating use—that is, not selling. And not selling means no new housing.

A linkage fee’s level of impact on these hold/sell decisions will depend on the value of the existing uses relative to the land. And where it will have the greatest tendency to hinder sales for redevelopment is in areas with lower land values where feasibility is currently marginal, such as the Rainier Valley, Northgate, and the International District—in other words, the very locations where the City most needs new housing to meet its goals for sustainable development.

Furthermore, most larger-scale housing developments require the assembly of parcels with multiple owners. The reduced likelihood of a sale caused by a linkage fee will be compounded by every individual sale that’s necessary—and it only takes one refusal to kill the whole deal. Anyone with experience in development knows that land acquisition and assembly is one of the most challenging steps in the process.

Sellers can be motivated by numerous reasons, but one scenario that’s easy to understand is the owner who wants to sell out and retire: the higher the price, the sooner they can retire. Slap on a million dollar linkage fee, and maybe they’ll wait it out through the next development cycle—perhaps 7 years or more—until market rents rise enough to offset that million dollar hit to their nest egg caused by the linkage fee.

The relationship between land values and redevelopment can be readily observed in neighborhoods all over Seattle where the market has become hot. As localized demand for housing increases and market rents rise, developers can pay more for land. And that’s when you start to see an uptick in property transactions for redevelopment—it’s the reason there are too many cranes to count in Pike/Pine, but none in Rainier Beach.

Given that every development project is unique, and given how the market varies over both geography and time, it’s delusional to believe that the City could set a linkage fee rate in some kind of “sweet spot” that wouldn’t end up sabotaging land transactions for redevelopment. Pickford asserts that a linkage fee could actually increase housing supply by directing more funds to housing production, but the risk is that each typical midrise housing project made infeasible by a linkage fee will mean another couple hundred people competing for existing housing and pushing the poor out of Seattle. And for each project rendered infeasible, it would take roughly 25 feasible projects to create the number of affordable units equivalent to the market units not built due to the linkage fee.

Lastly, for cases in which the developer already owns the land, it is even more clear why a linkage fee would impede redevelopment. The decision to invest in redevelopment will be based on the risk versus the return, and the linkage fee will reduce the return. It’s really that simple. Even property owners with deep pockets can opt to do other things with their money if redevelopment becomes a less attractive investment. They can just wait it out until rents rise enough to offset the loss of returns caused by the linkage fee.

Debunking the Evidence

The first piece of evidence Pickford presents to make the case that the factors I describe above would not impede housing development is historical data showing that the number of homes and condos for sale in Seattle is not influenced by average sales price—that is, people aren’t more inclined to sell their homes when prices are high, and vice-versa. However, most people who are selling homes live in them, and therefore most will be purchasing (or renting) another home in the same housing market with the same price trends. Therefore it makes all the sense in the world that sales price wouldn’t effect sales volume—for homes.

In contrast, sales that lead to high-density housing development are most often commercial properties, and the owners are typically investors who have the option to put proceeds from a property sale into other investments that don’t follow the price trends of the housing market. For example, the hit in property value caused by a linkage fee might mean the seller could only buy 800 shares of stock instead of 1000 with the cash from the sale, such that keeping the property makes more financial sense. The upshot is that data on home sales tell us very little about the property transactions that matter most for housing production, and thus are not credible evidence to support Pickford’s argument.

The second type of supporting evidence provided by Pickford is national studies showing that Inclusionary Zoning (IZ) has had no effect on the production of housing. Most of these studies look at cities in California where IZ is common. But a critical difference between a linkage fee and the IZ programs in California is actually emphasized in one of the papers cited by Pickford:

“It is worth reiterating that the programs we analyzed offer housing developers numerous cost-offsets, in accordance with California’s Density Bonus Law, to help make the inclusionary requirement revenue-neutral.”

If an IZ program is “revenue neutral†it means that it would not cause any reduction of land value, and therefore no impacts on housing production would be expected! In contrast, Seattle’s proposed linkage fee offers zero in the way of cost-offsets. Thus the results of all of the California IZ studies should be presumed to have no relevance to linkage fees.

Another shortcoming of the IZ studies cited by Pickford is their focus on single-family houses. For one thing, Seattle’s proposed linkage fee wouldn’t even apply to single-family, but more importantly, suburban single-family home development tends to involve land transactions that differ significantly from those involved in high density urban infill. In any case, perhaps not surprisingly, the one cited analysis for single-family homes outside of California (suburban Boston, where minor cost-offsets are typical) found “some evidence that IZ has constrained production and increased the prices of single-family houses.â€

Pickford also highlights a result in one of the studies that multifamily production increased after IZ was imposed, yet neglects to mention that the reason this happened was that production shifted from single-family to multifamily—a process that could not possibly happen in the case of Seattle. This same study found that single family house prices increased under IZ, which, of course, is the expected effect of a linkage fee if it doesn’t push land values down.

Ironically, evidence that a linkage fee would impede housing production is inadvertently provided by one of the papers cited by Pickford:

“The passage of the 1986 Tax Reform Act is associated with a sharp drop in new housing production. The act ended favorable tax treatment of market-rate rental housing, which effectively subsidized that housing. In almost all jurisdictions surveyed, housing production figures dropped significantly after 1986.”

In terms of the impact on land values, eliminating a tax subsidy for multifamily is effectively the same thing as imposing a linkage fee. So it’s completely reasonable to expect the result of a linkage fee to be the same: significantly less housing produced.

Lastly, Pickford’s citation of two impact fee studies as evidence is even more tenuous than the IZ studies, because the effects are attributed to other factors, as the authors explain:

“The finding that land values fall, despite the fact that the increase in new home prices exceeds the total value of the fees, can be attributed to developer uncertainty regarding future increases in fees.”

“Our theoretical model shows that impact fees may expand housing construction within suburban areas by reducing exclusionary regulations and increasing the percentage of proposed projects receiving local government approval.”

Housing Supply and the Precautionary Principle

In assessing the potential impact of a linkage fee, it is important to remember that the root cause of Seattle’s housing affordability crunch is that housing production has not kept up with demand. Therefore, any proposed policy such as a linkage fee ought to be highly scrutinized to ensure that it won’t hinder the development of new housing.

Given the well-founded reasons a linkage fee can be expected to impede housing production (see above), the burden of proof falls on those who support the fee to prove that it would do no harm—a.k.a. the precautionary principle. By this measure, Owen Pickford’s attempt is clearly a failure, and reads more like a predetermined answer grasping for straws of evidence. And not only does Pickford’s argument lack evidence, it ignores fundamental human nature: In what universe does the option of getting more cash sooner for an asset not incent an investor to sell, and vice-versa?

It would be great if the linkage fee was a “free lunch” solution to fund affordable housing, but as is always the case in the real world, there is no free lunch. And what’s even worse with a linkage fee is that it’s greatest negative impact on housing production will occur precisely in the locations where redevelopment economics are already marginal—the very places where Seattle needs new housing most. There are better solutions to address affordable housing in Seattle, and that is where urbanists should be focusing their effort.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban planner with VIA Architecture, a firm that consults to clients who could be impacted by a linkage fee. This post was originally published at Smart Growth Seattle, and has been edited for clarity and emphasis.

Why New Market Housing Reduces Displacement

Most Seattleites understand that the public has an obligation to subsidize housing for the city’s most needy, and residents have voted twice to tax themselves to that end through the housing levy. What’s far less appreciated is the essential role of the private sector in sustaining affordable housing.

It’s probably safe to say that the average Seattleite-on-the-street believes that expensive new housing is a major cause of declining affordability. And that is a regrettable thing. Because under current conditions of high demand for housing in Seattle, the reality is that new housing—regardless of price—actually abates displacement of those on the lower end of the income spectrum.

How can this be?

Consider the simplified case of a city with a total of five rentals ranging from cheap to expensive, and five people living in them with corresponding incomes. Along comes a wealthy newcomer who offers more for the most expensive unit, so the landlord raises the rent and the newcomer gets the unit because the current tenant can’t afford to pay that much.

The person who was displaced then offers more for the next cheapest rental, and so that landlord raises the rent, displacing the current tenant, who then bids up the next cheapest rental, and so on. In the end the person left without a place to live is the one with the lowest income of the five original renters.

Now consider how that scenario changes dramatically when there is one simple difference: a newly built expensive rental is available. The wealthy newcomer rents that unit, and that’s it—nothing changes for any of the existing five renters. No rents are raised, and no one is displaced. As counterintuitive as it may seem, the creation of a new expensive rental prevented displacement of the poorest renter.

Today in Seattle, the scenario of the lacking new unit is the fundamental process behind declining affordability and increasing displacement. And that’s why the ever popular sport of bashing “greedy developers” for building “luxury” housing is actually doing more harm than good.

Yes, of course Seattle’s housing system is far more complex than the above thought experiment. But none of those complexities negates the fact that the root problem is we’re not making enough room for newcomers. Still, this idea tends to encounter remarkably spirited resistance in progressive circles. Here are five common objections and why they are misguided:

- New housing causes displacement because older, cheaper housing is demolished to make way for it.

In recent years the ratio of new to demolished housing in Seattle has been about eight to one, which means that displacement prevented by new housing far outweighs any displacement caused. For high density housing the ratio is more likely in the range of 50 or 100 to one. That’s because a lot of new high density housing is built on parking lots or spent commercial buildings, as is readily observed in the city’s growing neighborhoods such Capitol Hill, Ballard, or downtown.

- New expensive housing drives up rents of surrounding housing; owners of new housing keep their units vacant to drive up rents; outside investors are buying up housing in Seattle and jacking rents to cover the inflated prices they pay.

The simple reason all of these related claims have no merit is because the primary determinant of rents is demand. And neither the existence of expensive housing, nor vacant units, nor inflated rents can create demand. These factors may introduce short-term marginal upticks, but over the long-term, rents always fall back in line with demand. This is simply indisputable reality, as verified by decades real estate market data.

- Housing consists of multiple bifurcated markets, so new expensive apartments do not affect prices of any other type of housing.

Regarding price, the thought experiment discussed above illustrates that in a large housing market there is a continuum of prices that allows renters to easily move up and down the market as needed—in other words, there is no financial bifurcation. Regarding housing type, bifurcation can be a factor, but the fact is, every new apartment added to the stock absorbs demand from a household that otherwise may have been forced to compete for other options. For example, a person who can’t find a cheap enough apartment may end up renting a room in a shared single-family house. Ultimately, every unit built relieves the entire market.

- The market cannot provide affordable housing.

It is no secret that the raw costs of production are simply too high for new housing to be affordable to a significant swath of the lower end of the income spectrum. But to claim that the market doesn’t provide affordable housing is highly disingenuous. Past census data and market surveys show that about three quarters of Seattle’s rentals were affordable to households earning 80 percent of the area median income. Today’s new housing becomes tomorrow’s affordable housing as it ages. Furthermore, because new housing absorbs demand, it reduces market pressure to renovate older, cheaper housing, thereby helping to preserve these low-rent options and reducing displacement.

- It’s a lost cause because we can’t build fast enough to get ahead of demand.

Even if production isn’t keeping up with demand, each new unit still has the potential to prevent one poor household from being displaced. It’s far from a lost cause to the person who can afford to stay in his or her home because just one additional unit of housing was built. This is not to say that building new housing will solve the whole problem. Subsidies will always be necessary to provide decent housing for the poorest households, as has been true in cities for centuries. But when so many people want to live here, the less new housing we build, the bigger the subsidy problem becomes.

>>>

If Seattle hopes to successfully tackle affordability, the critical role of market housing must be given more weight in policymaking. Take for example Capitol Hill, one of the city’s most in-demand neighborhoods, for which a policy choice has been made to not allow high-rise buildings, a policy that will curtail the creation of new housing by hundreds, if not thousands of units. And that translates to hundreds if not thousands more lower-income residents displaced from the neighborhood. Limiting height or density in places where there is strong demand is putting aesthetics before social equity.

In the public conversation about housing affordability in Seattle, rigid progressive ideology all too often leads to the demonization of private developers. But this can only lead to failure, because it will encourage policies that attempt to solve the problem at the expense of market production, such as the City’s proposed linkage fee.

Again, to be clear, no one is saying that market production alone will solve Seattle’s affordability problem.

There will always be some level of subsidy necessary, but that level will be determined by the balance of supply and demand. If market production continues to fall behind demand, the need for subsidy will balloon to the point where it becomes essentially unsolvable, as it has in San Francisco. And even if some households are protected from displacement through subsidized housing, the displacement caused by housing scarcity will simply shift to the next poorest households not protected.

It’s really not that complicated. Seattle has a housing shortage. Every occupied new unit of higher cost housing translates to one less higher income household competing for a limited amount of existing housing. And whenever there are more people who want housing than there are housing units, it will be the poorest who lose.

>>>

This post originally appeared on PubliCola.

We Already Have The Tools To Meet Seattle’s Need For Affordable Housing

Concerns over rising housing prices in Seattle have once again provoked heated public debate over what to do about it. In response, City Council’s proposed solution for funding subsidized affordable housing is a so-called linkage fee—a extra tax on all new development based on the amount that’s built. As I have argued previously, the linkage fee has serious shortcomings and is likely to exacerbate the very problem it is intended to address by either increasing the cost of new housing, or slowing its production.

What most Seattle policymakers appear to be overlooking is that Seattle’s projected affordable housing needs could be met by simply strengthening existing, proven programs, without resorting to an untried, complicated linkage fee that is both unfair and counterproductive. The true solutions staring us all in the face are the Housing Levy and the Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE), combined with robust production of market housing that will help keep prices in check by absorbing demand.

What is Seattle’s need for affordable housing?

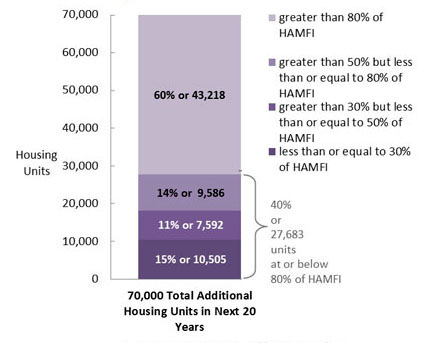

According to the Seattle Office of Housing, over the next 20 years there will be a demand for 28,000 new units of housing affordable to households with incomes at or below 80% of area median income (AMI). That’s equivalent to an annual average of 1400 units, or, to put it in perspective, about $350 million worth of new rentals per year. Separated by household income range, the Office of Housing’s projected average annual need is as follows:

- 0 – 30% AMI: 525 units/year

- 30 – 50% AMI: 380 units/year

- 50 – 80% AMI:Â 479 units/year

What do Seattle’s affordable housing programs produce?

Seattle’s current Housing Levy generates about $20 million per year from property taxes to fund affordable housing. During 2010 – 2013, Levy funds were applied to projects that have created an average of 417 units per year for households with incomes of 60% AMI and below. The Levy costs the owner of a median-value Seattle home $60 per year.

The MFTE offers a 12-year property tax exemption on multifamily buildings if they set aside at least 20 percent of the units for incomes in the range of 60-90% AMI. As of 2013 there were just over 3,000 MFTE units in active operation and another 1300 units approved. That corresponds to an average of 291 units created per year, though over the past two years the rate has been higher at about 700 – 800 per year. The tax exemption that enables the production of these affordable units corresponds to an additional annual tax impact of a mere $10 per median home.

Additional income-restricted units are produced by the Seattle Housing Authority using primarily federal funds, and by other non-profit affordable housing developers not relying on Housing Levy funding. The City of Seattle does not keep an inventory of these units, but they can be expected to make a significant contribution. For example, at Yesler Terrace the Seattle Housing Authority has plans to build 390 new units of housing for <60% AMI.

How affordable are Seattle’s market rentals?

The most current analysis available from the Office of Housing (2006-2010 data) shows that about three quarters of Seattle’s total rental units are affordable to a household with income of 80% AMI. Broken out by income range, the percentage of units affordable are as follows:

- 0 – 30% AMI:Â 11%

- 30 – 50% AMI:Â 22%

- 50 – 80% AMI:Â 42%

Because some households choose to rent units cheaper than what they can “afford” based on the standard formula, market housing that’s affordable still may not be available to lower income households. The Office of Housing data show that there is a surplus of over 7000 units affordable and available in the 50-80% income range, while there are deficits in the lower income ranges.

The Solution: Build on Success

The information presented above reveals that the combination of the Housing Levy, the MFTE, and existing affordable market rentals is already meeting a large portion of Seattle’s projected future need for affordable housing. For simplicity, let’s assume that over the next 20 years the City will need about 1000 units per year in the “low-income” range of 0 – 60 % AMI, and about 400 units per year in the “workforce” range of 60 – 80% AMI.

In recent years, Levy-funded projects have been producing two fifths of Seattle’s future low-income housing need. If the Levy was increased by 2.5 times, it could be expected to meet the entire need for 1000 units per year (assuming similar leveraging of other funding sources). That would translate to a tax of $150 per year for the median homeowner, or $13 per month. Factoring in the anticipated rate of low-income units produced without Levy funds, and the potential for affordable housing development on City-owned land, the necessary increase in the Levy would probably be closer to 2X than 2.5X.

That leaves the workforce housing need, which can can be readily met by a combination of the MFTE and existing market rentals. On average, the MFTE has been producing nearly three quarters of Seattle’s projected workforce housing need. Note also that these units are inclusive—that is, they are in the same building and neighborhood as the market units—and they come at a tiny cost to the average taxpayer. In short, the MFTE is a highly successful program. Two refinements that could improve it are an extension of the 12 year expiration, and easing requirements for applying it to existing housing and renovations.

The fact that over two fifths of Seattle’s total inventory of market rentals are affordable to 50 – 80% AMI clearly demonstrates that the private market can play a major role in meeting Seattle’s workforce housing need. And the way to keep the prices of older market rentals down is to maximize the production of new market housing, which absorbs demand from higher income people moving to Seattle. In contrast, a linkage fee is likely to slow market rate production and drive up prices of Seattle’s existing stock. Seattle’s workforce housing need could also be better supplied by the market if the City would remove overly restrictive regulations on accessory dwelling units and backyard cottages in single-family zones.

Share the Burden

A key advantage of the property tax-based approach described above is that it spreads the burden across all property owners, as opposed to a linkage fee that extracts only from the relatively small fraction of properties that redevelop. Owners of high value properties that won’t be redeveloped for decades—the half a billion dollar 76-story Columbia Center, for example—would contribute nothing to affordable housing through a linkage fee. With a property tax, owners of the most valuable properties pay the most.

In addition, when the burden is shared through a uniform property tax, the impact becomes relatively small on individual property owners—and the additional expense is a tiny fraction of what owners have been gaining in appreciation in recent years. On the market housing side, the cost to the City for encouraging private development is essentially zero, and new development enlarges the tax base.

In retrospect, Seattle has done a good job addressing affordable housing, and has effective subsidy programs already in place. San Francisco’s housing prices are still about 50% higher than Seattle’s, which has everything to do with the fact that Seattle has had a lot more private market housing development over recent decades.

Seattle has work to do to address affordable housing, but it’s not a crisis—yet. If we can keep cool heads and avoid politically driven, counterproductive quick fixes such as the linkage fee, we can succeed by sharing the burden and building on success.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban planner with VIA Architecture, a firm that consults to clients who may be impacted by a linkage fee.

Seattle is a compassionate city faced, like all growing cities, with an affordable housing challenge. Most Seattleites hope to see their City successfully tackle that challenge with effective programs that help those most in need. But unfortunately, translating such good intentions into action is all too often distorted by politics. And the latest case in point is City Council’s rush to enact a “linkage fee.”

The proposed linkage fee would generate revenue for subsidized affordable housing by taxing all new development $5 to $22 per square foot of floor space in the project, or about 3 to 10 percent of typical multifamily development costs. The City estimates that the tax would raise five to ten times more revenue than the Incentive Zoning program currently in place. Proponents claim the tax would neither raise the rents of new housing, nor slow its production—in other words, an economic “free lunch” for affordable housing. If that sounds too good to be true, it’s because it is. Here are seven reasons why:

1. The “nexus” rationale for the housing tax is that creating jobs is a negative impact. The legal justification goes like this: People who live in new housing create demand for service jobs; the low-paid workers in these jobs can’t afford market-rate housing; therefore the builder of the housing is responsible to pay for subsidized housing.

By that logic, any activity that creates any economic output whatsoever externalizes the need for affordable housing and therefore should be taxed to pay for housing subsidies. Singling out housing development to pay the tax may appease the anti-developer sentiment common in many constituencies, but it is bad policy, especially given the fact that building new housing helps meet demand, thus keeping prices under control throughout the City.

2. The housing tax is unfair because it only applies to new development and not to existing property. If you are willing suspend disbelief and accept the above nexus argument, then it follows that all housing, whether existing or new, creates the same need for affordable housing. Why shouldn’t existing property owners contribute their fair share, especially when they have been benefiting from large increases in their property values as a result of Seattle’s success?

3. The housing tax is unfair because it doesn’t apply to single-family property. Again, if you accept the nexus argument, then single-family houses create a need for affordable housing just like any other type of housing. Why shouldn’t single-family home owners pitch in too? Not only are they enjoying windfall gains in their home values, but the fact that nearly 2/3 of Seattle’s zoned land is reserved for single family severely limits housing supply, which, in a high-demand market like Seattle, is the primary reason for rising prices.

4. The housing tax will exacerbate the very problem it is intended to address. The proposed tax will either raise the costs of development, or lower the prices paid by developers for land — both of which would lead to escalated rents.

When development costs rise, housing projects are not feasible if the market cannot support high enough rents to offset those costs. The inevitable result will be higher rent — if not now, then later, once the rental market inflates sufficiently to make development feasible again.

Alternatively, if the tax causes land values to drop, then keeping property in an existing money-generating use — e.g. a surface parking lot — becomes more financially favorable than selling the land for redevelopment. And that means less housing created, and more rapidly rising rents throughout the City due to suppressed supply. Ongoing demand would eventually push rents high enough to motivate property sales for redevelopment, but that delay could set back housing production by perhaps five to ten years or more.

In either of the above scenarios, the resulting increased rents will shift housing demand toward lower priced options. And that shift will cascade all the way down to the bottom of the market, reducing the availability of the cheapest market rentals, and creating additional need for publicly subsidized housing to make up for a larger affordability gap.

5. It is not a progressive tax. Proponents want to believe that linkage fees redistribute wealth from developers or high-income renters to the have-nots, but when all the effects are factored in that’s wishful thinking. That’s because the rent increases a housing tax would cause — whether by pass-through to renters or by suppressed supply — will always hit the poor the hardest, offsetting the gains made through the subsidized housing paid for by the tax.

When rents for new housing are forced up, vacancy rates drop for existing cheaper housing, driving up those rents, and ultimately squeezing out renters with the lowest incomes. Similarly, if depressed land values result in less housing production, the poorest renters will always get outbid for what’s left of the limited inventory at the low end of the market.

6. The substantial benefits of infill housing development are ignored. It is well-established that concentrating housing growth in urban centers provides a wide range of social and environmental benefits, as reflected in countless policies at all levels of government. In addition, development generates substantial new tax revenue that supports a wide range of City services. If all the positive impacts were quantified there would be justification for subsidizing infill housing development, rather than taxing it.

7. And lastly, linkage fees are probably not legal. Last week 13 local land use attorneys sent a letter to City Council arguing that the proposed tax would be illegal under State law. Perhaps that question ought to be settled before the city expends significant resources moving ahead with linkage fees?

The City of Seattle deserves better. Taxing housing to address rising housing prices is every bit as illogical as it sounds — like a snake eating its own tail. Rather than targeting taxes on development — a sector that actually plays a critical in keeping housing more affordable — solutions should spread the burden fairly across the City as a collective.

And in fact, Seattle already has two programs that do just that, namely the Housing Levy and the Multifamily Tax Exemption. Other solutions include utilizing publicly owned land for affordable housing, and City purchase and preservation of distressed affordable market rentals.

The proposed linkage fee is an untested new tax that would potentially impact billions of dollars of investment over the coming decades, and would have a host of unintended consequences that contradict its intent. Council’s current urgent focus on the tax is misguided. The Mayor has convened a committee tasked with developing a comprehensive set of affordable housing solutions, which is the right approach.

Council needs to take a breath and let go of the ill-conceived linkage fee.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban planner with VIA Architecture, a firm that consults to clients who may be impacted by a linkage fee. This post originally appeared on Crosscut.

We need housing — and jobs — near transit stations

Full build-out of the Rainier Beach light-rail station area would create a balance of businesses and housing. (Image Credit: VIA Architecture)

It is widely established that concentrating growth near transit is a key strategy for sustainable urban development. Historically, planning for transit station areas has focused on housing rather than employment — when most people think of transit-oriented development, they picture dwellings above street-level retail.

In recent years, however, the value of planning for employment around transit has become increasingly recognized for several reasons. From a practical standpoint, jobs near transit boost ridership and help leverage transit investments. But more importantly, creating a healthy balance between employment and housing is essential for growing a complete community that maximizes opportunities for both residents and workers.

In some station areas the primary need is for new employment that builds upon the assets of the existing community and becomes a source of living-wage jobs for locals. In other cases, the main challenge is to avoid displacement of existing businesses. Industrial jobs are particularly challenging since they can conflict with residential uses, and often rely on the availability of cheap land.

Of course the catch is that there’s no easy formula for bringing high-quality jobs to desired locations. Do innovation districts just happen, or can the public sector help them along? My firm, VIA Architecture, recently engaged in two employment-based planning efforts that illustrate concepts and approaches, as described below.

Employment-based redevelopment near the Rainier Beach light-rail station would create an ideal location for a farmer’s market. (Image Credit: VIA Architecture)

Rainier Beach

Seattle’s southernmost Link light-rail station is in Rainier Beach, a highly diverse, relatively low-income neighborhood. Within a quarter-mile of Rainier Beach station are a handful of small businesses, and the housing is mostly single-family. There has been no significant redevelopment near the station since the trains started running in 2009.

The city recently completed a neighborhood plan that focused on opportunities in the station area. During this process, the community consistently expressed a high priority for redevelopment that creates high-quality employment that can improve economic mobility for residents, such as low-impact production, light-industrial, food-processing, education and incubator businesses.

To address this goal on the regulatory side, the city is developing new zoning that will incentivize educational, industrial and innovative commercial uses while promoting a vibrant, sustainable and walkable urban environment. Proposed zoning includes floor area or height bonuses for projects with the employment uses noted above, first-floor minimum height requirements for flexible accommodation of commercial uses and special allowances for loading.

With easy access to the industrial corridor that extends south from the Duwamish, Interstate 5, Sea-Tac Airport and downtown Seattle via light rail, as well as relatively low land costs, Rainier Beach is well situated for many types of innovative business pursuits. However, stakeholders also recognized the need to start with a specific sector that could leverage existing community assets for competitive advantage over surrounding areas, and the idea of a food innovation district rose to the top.

Rainier Beach is home to Seattle’s largest urban farm, and its diverse population provides a wealth of ethnic food knowledge. These assets provide a unique opportunity to leverage its light-industrial zone to become a hub of food and agricultural production, combining educational and training facilities with processing and distribution.

To catalyze the growth of a food innovation district, the planning team proposed an opportunity center for food education and entrepreneurship. This facility would combine commercial and training kitchen facilities, classroom space, office space, meeting areas, computer lab and community gathering space.

Conceptual sketch of the Opportunity Center for Food Education and Entrepreneurship. (Image Credit: VIA Architecture)

The city convened a workshop to gather input from potential partners and users of such a facility, including Seattle Tilth, the Emergency Feeding Program, Rainier Valley Food Bank, Project Feast and Fare Start, as well as the Seattle community colleges, Renton Technical College and Bainbridge Graduate Institute.

Input from the workshop led to a prototype building design. Unfortunately, the Rainier Beach station area lacks any existing building stock suitable to be adapted for the center, so new construction will be required. The next steps to implementing the center involve establishing partners, developing a business plan and space programming, securing a site and financing, construction, and lastly, operating the facility.

Portland ETOD

The Portland-Milwaukie light-rail extension, due to open in 2015, will have two stations in Southeast Portland’s Central Eastside, one of the city’s most important and dynamic industrial and employment centers. To address this unique environment, the city and its consultant team have been developing a new model for station area planning known as employment transit-oriented development, or ETOD.

The overall goal of the city’s ETOD approach is to strategically intensify and diversify the range of commercial uses on industrial lands, with the primary intent of increasing jobs, but also to leverage transit investments. At the same time, the city is intent on controlling land speculation, since high costs tend to push out many of the desired businesses. While there is already streetcar service in the Central Eastside, it is not another Pearl District, nor does the city want it to be.

A key strategy will be to reduce conflicts between the Central Eastside’s long-established businesses such as lumber and mill works, a dairy, and boat repair, while also welcoming an increasing number of new small, nimble technology and production companies that value a close-in location. These “makers†are seen as an important next generation of commercial enterprise whose employees are likely to bike commute and patronize the small-scale restaurants, bars and lunch spots that have begun to populate the area.

Another important piece of the ETOD puzzle is an intensification of land use in buildings that blend industrial and production uses on the ground floor with flexible office spaces on multiple floors above. The goal is buildings that can provide a delicate balance between a diversity of new businesses, and an industrial core of users that rely on lower land values to stay in business.

The newly constructed Pitman Building in Portland’s Central Eastside combines commercial kitchens with office space above. (Image Credit: Deca Architecture)

This configuration is already beginning to emerge in the Central Eastside, and one of the best examples is the newly constructed Pitman Building, with 11,000 square feet of space for six production kitchens on the first floor and 3,000 square feet of office space on the second floor. The area’s supply of historic buildings is also an asset, as exemplified in the recently renovated Ford Building, a former Model T assembly plant that now houses office, retail, artist studios, and a variety of small, creative businesses.

The role of partnerships

Lastly, partnerships between large institutions and the private sector are an essential ingredient for catalyzing true innovation districts. With the goal of creating an environment suitable for 21st century industry and providing meaningful occupation, many cities are establishing collaborations with universities that have a technical research and innovation focus.

For example, New York City has established a collaboration called Cornell NYC Tech, with Cornell, Teknion (an Israeli technical university) and Google. In Portland, there is a huge opportunity to tap into the synergies between the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland State University, the burgeoning “makers†industry, and/or a corporate giant such as Nike.

The Oregon Museum of Science and Industry owns significant riverfront property adjacent to future light rail, and has great potential to leverage its location at a regional transit gateway and bring culture and complementary employment to the Central Eastside. In this case, the most advantageous outcome may be a new large tenant that would both benefit from and contribute to new synergies with existing business clusters.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban planner with Via Architecture and is the creator of Citytank.

Note: This post originally appeared in the Daily Journal of Commerce.

When change occurs as rapidly as it has been in Seattle, misplaced blame runs rampant. And one of the most egregious examples is the contention that the construction of new housing is the cause of declining affordability—case in point, a coalition of Seattle neighborhood groups is currently advocating for a moratorium on new housing construction. But the reality in Seattle couldn’t be any more diametrically opposed: building housing at higher densities is actually a means to reduce the loss of existing low-cost housing.

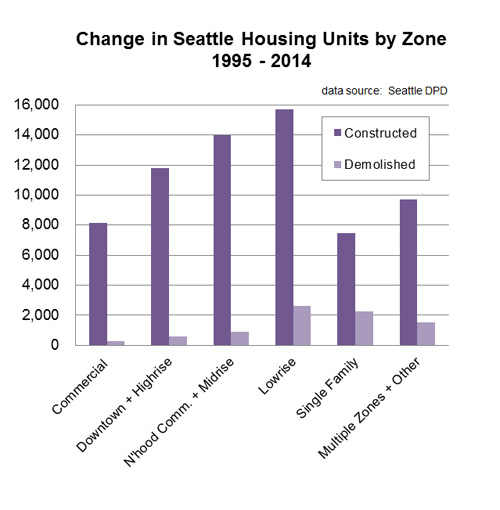

To understand why, start with the data. According to the Seattle Department of Planning and Development, from 1995 to 2014, 68,433 new housing units were built and 8,724 units were demolished. That corresponds to a ratio of eight, meaning development is staying way ahead of the game in terms of net increase in housing, which helps affordability across the board by absorbing demand.

Furthermore, a nontrivial chunk of the demolishing likely had nothing to to do with housing redevelopment—the 8,724 includes units demolished for any reason, not just to make way for new housing. During 1996 to 2005 (newer data unavailable), over 25 million square feet of non-residential floorspace was developed in Seattle, and it’s reasonable to assume that some of that resulted in demolished housing. It is also reasonable to assume that some housing was demolished simply because the buildings had aged beyond their lifespan.*

While there is no question that housing development results in a lot more housing units gained than lost, it is also true that new housing is typically more expensive to rent or buy than old housing. And if new housing actually does take out existing housing, then the new units will likely be more expensive than the units that were lost. First, as alluded to above, to some extent this process is normal and cannot be avoided, because housing ages and eventually has to be replaced.

But second, and more importantly, it is a logical fallacy to conclude from this that housing development is inherently bad for affordability. Accurately assessing the impact requires a comparison to what would have happened absent the new housing. And in a high demand market like Seattle, the result would be greater competition for a limited supply of existing housing, which would drive up the rents, likely leading to renovation to meet demand for higher quality units. In other words, saving the existing units would not preserve their affordability for very long, and in fact, the system-wide effect would be a net loss in affordability caused by suppressed supply.

Looking at the housing data by zone in the above chart, it is clear that, on average, higher density development results in fewer units lost for every unit built. Given the basic math involved, that shouldn’t come as a surprise. The more housing units that get put on a given amount of land, the less likely it will be that existing housing will need to be demolished to make space for it. As can be observed through0ut Seattle,** most high density housing projects replace parking lots or spent commercial buildings, and not much, if any, housing.

Given the objective reality, it is remarkable how high density development is still so often a prime target of ire from people concerned about the preservation of affordable housing. Instead of pushing for further restrictions and fees that impede high density development and make it more expensive, these folks ought to be advocating for policies that promote building to the highest densities wherever possible. The same goes if the concern is about preservation of open space, tree canopy, or streams. Put simply, when we build up, there’s more room left over in the City (and the region) for other things we value.

In an analogous policy disconnect, high density projects are also the City’s biggest target for the extraction of development fees to offset their supposed “impacts.” But as the City’s own data show, the higher the density, the lower the impact on existing housing. A more sensible policy approach would place the tax burden of subsidizing affordable housing on low density properties, because inefficient land use is one of the root causes of Seattle’s affordability challenges.

The City’s ultimate example of misplaced blame is South Lake Union (SLU), which has long been a lightning rod for denunciation regarding affordable housing and gentrification. And last year SLU became the first neighborhood to be subjected to the City’s increased Incentive Zoning fees that are used to fund affordable housing. But guess what: From 2005 to 2014 (1995-2004 data were not parsed) there were 2,132 housing units built or permitted in the SLU zones, and only six housing units demolished. Not to mention the numerous subsidized affordable housing projects recently built in the neighborhood. It’s as if the City is intent on punishing the very places where things are being done right.

Lastly, none of this is saying that preserving existing buildings for affordable housing isn’t one of many potential strategies that the City policymakers should be exploring. However, we should not expect that the significant cost for the necessary subsidies can or should or be borne by a property owner who happens to own an old building. If the City wants buildings preserved to help meet affordable housing goals, then the City as a whole should step up and pay for it, and stop misplacing blame on housing development, which is actually part of the solution.

>>>

*For a quick thought experiment, assume that housing has a 100-year lifespan, and that Seattle built 300,000 housing units over 100 years and then stopped. At that point, the City would start to lose 3,000 units per year simply due to the lifespan of the buildings. For comparison, between 1995 and 2014, Seattle lost an average of 459 housing units per year to demolition.

**In this King5 news video, “monster” housing developments are vilified for causing loss of affordable housing, but the four projects shown that I could identify appear to have displaced a grand total of one housing unit!

Â

Council Study Reveals The Inherent Futility Of Incentive Zoning

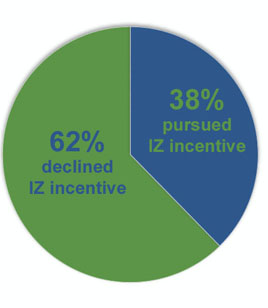

Seattle City Council asked for a reality check on Incentive Zoning (IZ) and now they have their smoking gun:Â Since the Program’s inception in 2001, 62% of eligible development projects declined to participate. That outcome demonstrates that the IZ Program is not only fundamentally broken, but also has resulted in the loss of significant public benefits, and hindered progress towards the City’s own sustainable development goals.

It’s pretty simple:Â Most developers said “no thanks” to IZ because the incentive offered by additional development capacity was not sufficient to offset the additional risk and cost. And one component of that additional cost is the requirement to include subsidized affordable housing in the project, or to pay for its construction elsewhere, a.k.a. an in-lieu fee.

It’s pretty simple:Â Most developers said “no thanks” to IZ because the incentive offered by additional development capacity was not sufficient to offset the additional risk and cost. And one component of that additional cost is the requirement to include subsidized affordable housing in the project, or to pay for its construction elsewhere, a.k.a. an in-lieu fee.

Given the historic low participation rate in IZ under its existing encumbrances, it would seem obvious that increasing the requirements for affordable housing will only tip the scales further toward non-participation, in which case zero affordable housing is produced. When the toll is raised, the gains made from the projects that still opt in to the Program will be offset by the increasing portion of projects that decline. And this inherent “diminishing returns” aspect of IZ is why it should never be expected to have a consequential impact on Seattle’s affordable housing needs.

I wrote “would seem obvious” above because apparently it is not obvious to Seattle City Council, and all indications are that some Councilmembers will be seriously considering either raising the IZ in-lieu fees (again), or more likely eliminating the in-lieu fee option altogether and thereby requiring developers to subsidize the full cost of including affordable units in their projects.

In the South Lake Union neighborhood, Council recently imposed in-lieu fees that are up to 43% higher than the historic fees in downtown, and what is the result so far? Of 20 eligible development projects in the pipeline, 14 are not participating—a no thanks rate of 70%. South Lake Union could be considered a best case scenario for IZ, since it is one of the hottest real estate markets in the country. But even under ideal market conditions, for most projects the incentive was insufficient to overcome the encumbrance.

Based on the estimates of Council’s affordable housing consultant, mandating inclusion of affordable units in projects would be equivalent to jacking the in-lieu fees by a factor between about two and four.* It’s hard to conceive how this would not lead to a precipitous drop in IZ program participation. And again, that would result in even less affordable housing produced, along with underdevelopment in urban centers that runs counter to Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan, as well as regional goals for sustainable growth. Same goes for tweaking IZ to require affordability levels deeper than 80%AMI (i.e. where the real need lies)—the opportunity cost to developers will rise significantly due to the greater requisite subsidy, and the IZ participation rate will drop.

Since 2001, IZ in Seattle has generated about $27 million from in-lieu fees, which resulted in the production of about 600 affordable rental units, if the effect of leveraging funds from other sources is included. Council’s consultant predicts that because funding sources that have been leveraged in the past are drying up, from here on out the City should anticipate about a doubling of their expenses to produce affordable housing*—in other words only about 300 units could be produced from that $27 million. For reference, $27 million would cover the turn-key production costs of only about 110 typical multifamily units. To put those numbers in perspective, during that same time period, some 46,000 multifamily units were built in Seattle.

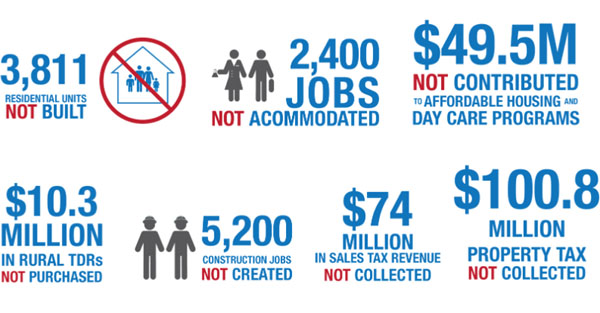

Some would argue that even though IZ produces a miniscule amount of affordable housing relative to the need, it’s still better than nothing. But this argument becomes indefensible when you consider the negative impacts of the underdevelopment that IZ can cause. The Downtown Seattle Association has published estimates of a wide range of public benefits that were forgone based on 25 projects in downtown and South Lake Union that opted to not participate in the IZ program, illustrated below:

City Council must be held accountable for putting this magnitude of public benefit at risk through the imposition of IZ. Granted, the added encumbrance of providing affordable housing is only one of many reasons developers might opt to forgo the maximum development capacity allowed through IZ. But those other factors will always be part of the development equation. And in any case, piling on affordable housing is guaranteed to tip the scale in the wrong direction, especially if the requirements are made more onerous, which is the direction the political winds are blowing.

The potential sacrifice of 3,811 new housing units is the most glaring illustration of how IZ is an intellectually bankrupt policy. The biggest driver of Seattle’s current housing affordability crunch is demand outstripping supply. When thousands of new housing units go unbuilt, that means thousands more households competing for existing housing, and at the end of the day, it will be the poorest households that get priced out. And it also means thousands more housing units likely to end up built in sprawling outlying areas.

To sum it up with bad cliches, Incentive Zoning is like trying to squeeze blood from a stone, and robbing Peter to pay Paul, and shooting yourself in the foot, all rolled into one. Given that in this case the stone is such a politically expedient scapegoat, there is no question that City Council’s life would be easier if the above cliches weren’t so apt. But the sooner Council accepts the inherent futility of IZ, the sooner they can get on with the hard work of developing better housing affordability strategies—that is, strategies that—unlike IZ—encourage market production of housing supply to help ease prices, have the potential to generate funds for subsidy commensurate with the need and cost, and place the tax burden on all property, not just new development.

>>>

*The Cornerstone Partnerhip’s estimates provided to City Council: Opportunity cost to developer of affordable units built in project = $100k – $200k/unit; In-lieu fee = $56k/unit; Historic cost to City = $44k/unit; Future cost to City = $95k/unit

>>>

This post originally appeared at Smart Growth Seattle.

Workforce Housing in Seattle: Myth vs. Reality

For the better part of the past decade, both advocates and policymakers have been decrying Seattle’s perceived lack of housing affordable to people with incomes in the lower-middle range—so-called “workforce housing.” As a result, Seattle has implemented and is continuing to expand a program known as Incentive Zoning intended to create subsidized workforce housing through fees imposed on new development.

But there’s one rather important thing wrong with this picture:Â Available data show that there is no shortage of workforce housing in Seattle.

For reference, workforce housing is typically defined as housing that is affordable to households with incomes between 60 and 100% of area median income (AMI). In Seattle, 80% AMI corresponds to $49,440/year ($24/hour) for a single-person household. Assuming the standard that 30% of income is spent on housing, that translates to an “affordable” rent of up to $1342 per month.

For all the attention workforce housing gets, there’s surprisingly little up-to-date, hard data available on how much housing is out there priced at workforce affordability levels, compared to how many households there are that need it. King County analysis based on a 2009 survey of market-rate rentals found that a whopping 83% of units in Seattle were affordable to a household earning 80% of AMI. For 50% AMI, 37% of Seattle’s rental units were affordable. Across King County and the greater region, data reveal a similar pattern of excess housing supply at workforce income levels, along with a sharp increase in need the further income drops below workforce levels.

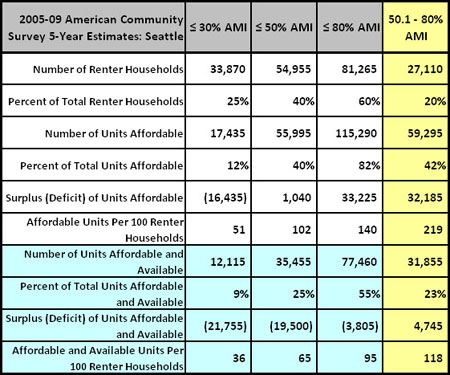

Based on the raw numbers there would seem to be plenty of existing workforce rental housing in Seattle, but one complicating factor is that some households may be renting housing that is cheaper than what they could afford according to the standard 30% formula. This “downrenting” has the effect of reducing the availability of housing that is affordable to lower incomes. The affordable housing advocacy group Housing Development Consortium has published some analysis by the Seattle Office of Housing on downrenting, and the results are summarized in the table below:

Looking specifically at households with incomes between 50 and 80% of AMI (yellow column)—which is the lower portion of the workforce range—there was a surplus of over 32,000 housing units with affordable rents. Put another way, for every 100 households in the 50-80% AMI range, there were 219 affordable rentals in Seattle.

After subtracting the number of units being rented by households earning more than 80% of AMI, there is still a surplus of 4,745 rental units affordable and available to 50-80% AMI households; for every 100 households in the 50-80% AMI range, there were 118 affordable and available rental units in Seattle. In other words, even when downrenting was accounted for, there was still no shortage of workforce housing.

Since 2009 housing costs have risen faster than incomes, so current data would likely show some reduction in affordability. And rents vary significantly between different neighborhoods. But even with those caveats, it’s hard to imagine how anyone could interpret the available data as proof of a dire need for programs to subsidize workforce housing in Seattle. Yet currently Seattle City Council’s affordable housing efforts are focused on an extensive examination of how to do exactly that using Incentive Zoning. Here’s how Council justifies it:

For example, a public school teacher’s starting salary of $42,000 suggests that he or she should not pay more than $1,050 per month (30%) for housing. Yet the average rent in Seattle for a 2 bedroom / 1 bath apartment is $1,466.

That’s right, we have a workforce housing crisis because a single person earning far less than the City’s average income can’t afford the City’s average rent for an apartment with an extra bedroom, never mind the half of the housing stock that rents below the average. And so apparently therefore we need to exact a toll on new development through Incentive Zoning so that someone making up to $49k can live in a subsidized apartment in a brand new downtown high rise. Seriously—if any of you reading this were in those shoes, would you feel entitled to that?

Meanwhile Council balks when it comes to solutions that would support meeting workforce housing needs through private development—no public expense necessary—such as microhousing, accessory dwelling units, meaningful upzones in lowrise zones, removing off-street parking requirements, and other strategies that could reduce the cost of producing housing.

In previous posts I have pointed out the numerous flaws in Incentive Zoning—how it defeats its own purpose by restricting supply and increasing the cost of housing production, how it’s based on an outdated paradigm that sees dense development as negative impact to be mitigated rather than a critical sustainability solution, and how its inherent limits preclude it from ever generating more than a drop in the bucket relative to the need.

Now we can add to that list of flaws the fact that Seattle’s Incentive Zoning Program was designed to subsidize workforce housing, even though the data indicate that the City already has enough. Available workforce housing may not be brand new housing. But even if new housing has rents higher than workforce affordability levels, it will still help preserve the availability of workforce housing by absorbing demand from a high-income renter who would otherwise be competing for, and driving up the prices of existing housing.

The City’s real housing need is at the deeper affordability levels, as the data clearly show an increasing deficit of affordable rentals as incomes drop below 50% AMI (see data table above). And yet another pitfall of Incentive Zoning is that even though it doesn’t address the real need, it creates the false impression that electeds are taking meaningful action to solve a housing problem. That is, Incentive Zoning is a politically expedient distraction.

To sum it up succinctly: Why are we applying an counterproductive tool to solve a problem we don’t have? We can and must find better solutions to address Seattle’s actual affordability needs.

>>>

P.S. For brand new info on the ineffectiveness of Seattle’s Incentive Zoning Program, check out this presentation by the City’s consultant, who found that 62% of of projects eligible for the incentive have opted not to develop the additional floor area. In other words, for most projects the Program is not an incentive because the fees are already too high.

>>>

This post originally appeared at Smart Growth Seattle.

Why Building Housing In Seattle Is Essential For Social Equity

One of the biggest threats to social equity in Seattle is a shortage of housing. Because when demand for housing overwhelms supply and drives up prices, it is the poor who lose. And the essential solution is this: build more housing.

Landlords and developers both do well in a seller’s market for housing. And the affluent are fine too, because they can always outbid those with less financial means for the limited housing that is available.

But the people who do not fare well are those in the lower end of the income spectrum, who are denied access to the all the opportunities and benefits of living in a a prosperous city like Seattle. When demand is not met by supply, inflated prices across the board put housing increasingly out of reach. And those with the lowest incomes are always priced out of the market the soonest and the furthest.

To be clear, government subsidy for housing is also necessary for the deeper levels of affordability. And due to high costs of production, new housing can often be too expensive for a significant portion of lower-income households. Nevertheless, in a high-demand housing market like Seattle’s, increasing the supply of market-rate housing is imperative for equitable access to housing. Here are ten reasons why:

- First of all, increased supply puts downward pressure on prices throughout the housing market, and that preserves affordability for more households.

- Because supply enable more households to find an affordable option, limited funds for housing subsidy can go further to provide more financial help for the lowest income households who need it most.

- More housing means more choices for people to find an affordable housing option that fits their unique needs, such as microhousing.

- Even expensive new housing helps, because every high-end unit that’s produced absorbs demand from a wealthy consumer who otherwise would be outcompeting those with lower incomes for existing housing.

- Likewise, even if new housing units are small they still absorb demand, which reduces competition for existing single family houses, and preserves more options for families with children to live in the city.

- When new housing is provided near good transit, more households have the option to go car free, which significantly reduces household expenses.

- When new housing is not available, demand will induce renovation of older housing, thereby removing it from the affordable stock.

- More housing expands the tax base and increases funds available to subsidize housing for the lowest income households through programs such as Seattle’s Housing Levy.

- The cost and financial risk of building housing falls on private developers and lenders, not on cash-strapped municipalities—social equity is improved with very little public expense.

- Lastly, in the bigger picture, increasing housing supply in Seattle supports widely adopted sustainable development goals to address sprawl, energy, and climate change, all of which disproportionately impact the less fortunate, whether at the local, regional, or global scales.

In comparison to the above list, the purported downsides of housing development are less tenable. One commonly cited concern is displacement of existing affordable housing. But most of the larger multifamily infill projects in Seattle are built on empty lots or spent commercial buildings, and do not cause any such displacement. In cases where new housing would take out existing low-rent units, preventing the development is likely to be a short-lived victory. Because if the location is desirable, the resultant pent-up demand will inevitably accelerate rent increases in any housing that was preserved.

In Seattle, most of the negative noise over new housing is about the impact on neighbors—views, shadows, aesthetics, undesirable tenants, parking, traffic. And what it boils down to is a choice between those who were lucky enough to get theirs first in Seattle, and those with limited financial means who want to find a place to live here now. If social equity is truly the goal, then the latter group must be given priority.

These battles over growth have played out countless times in Seattle, the current example being the debate over rolling back recent upzones in low-rise residential areas. If City Council decides in favor of those who wish to restrict housing development, we should all recognize that they will also be deciding against social equity.

The trends that are creating strong demand for housing in Seattle are not going away any time soon. Seattle has a massive, ongoing need for new housing to meet this demand and control prices. If supply continues to fall behind, not only will more lower-income households be priced out, but the subsidy required to make up for the widening affordability gap will increasingly eclipse available City funding resources.

If there was a shortage of shoes that drove prices so high that only the wealthy could afford good shoes and the poor were going barefoot, it would be obvious that increasing shoe production should be a priority to improve social equity. So too, with housing.

>>>

Photo of new housing at 13th and Pine on Capitol Hill by the author. This post originally appeared at Smart Growth Seattle.

Getting High In Residential Transit Station Areas

About 6 miles from downtown Vancouver just inside the eastern city limits is a residential neighborhood called Collingwood that looks like this from the SkyTrain:

And this:

And this:

And for perspective, a 2008 birdseye view of the whole area:

As I wrote back in 2008, this is what transit-oriented development (TOD) looks like:

Collingwood balances density with amenities: it has seven acres of park, an elementary school, a “neighborhood house,†a community gymnasium, and a daycare. It offers a variety of housing types at both affordable and market rates, with 20% of the units designed for families with children. There are towers ranging from 17 to 20 stories mixed in among 4- and 6-story mid-rise. Lower buildings and a park face the single-family zone to the south.

UPDATE:Â Collingwood has become the densest neighborhood in Vancouver.

What’s conspicuously lacking from the built environment, both in Collingwood and throughout Vancouver, is the Seattle “breadloaf”—the 6- to 7-story mixed-use residential building type that has become ubiquitous in Seattle’s growing urban villages. During my recent Vancouver tour I only spotted one, near the Commercial-Broadview SkyTrain station:

The difference between Collingwood and any TOD in Seattle outside of downtown—existing or planned—couldn’t be any more stark. The Collingwood SkyTrain station is about the same distance from downtown Vancouver as the Othello LINK light rail station is from downtown Seattle, but in contrast to a station flanked by ten high-rises, at the Othello station area the maximum building height is only 65 feet, and only one large-scale private development has been completed since the trains started running 4.5 years ago.

Two stops closer to downtown Seattle at the Mount Baker LINK light rail station area, the City began a planning process in 2009 that culminated in a recommendation for an upzone to heights up to 125 feet in a small portion of the station area. But in late 2013 a Council vote on it was derailed by 11th-hour neighborhood opposition. At the future LINK station due to open in 2021 in Northgate, about 7 miles north of downtown Seattle, heights up to 125 feet are allowed in some areas, though there have been no takers yet—only mid-rise breadloaves so far. At the future LINK light rail station on Capitol Hill, the City’s highest-density residential neighborhood outside of downtown, all that the community could agree on was a meager height increase from 65 to 85 feet.

Demand for housing in Seattle is not going away any time soon. And if we can’t build up, we will build out. Inside the city that means increased development pressure on underdeveloped or underutilized properties, including housing that is relatively affordable. Outside the city that means more sprawl and loss of farms and forests.

As with my previous posts on downtown Vancouver and Vancouver suburbs, I am not claiming that Vancouver’s urban form is perfect, nor that high-rise is a cure-all that belongs everywhere. My point is that if Seattle hopes to grow into the most sustainable city possible, high-rise will have to play a much larger role than it has. And Seattleites need look no further than the city across the border to see that it can work well. But if fear of heights continues to rule the day, ultimately both the City and the planet will suffer for it.

>>>

All photos except the birdseye taken by the author from the SkyTrain.

In The City in History (1961), Lewis Mumford describes the “regional city” as an alternative to formless, auto-oriented sprawl. The regional city consists of a central major city encirled by a network of smaller satellite cities, all connected by rapid transit. Apparently greater Vancouver, BC, was listening.

The photo above is in Burnaby, the first city east of Vancouver along the Skytrain line. It looks as if a section of downtown Vancouver was imported. No fear of heights here. In the photo below, a brand new 46-story residential tower rises from a sea of low-density housing adjacent to the Metrotown Skytrain station. Density near transit—pretty simple.

Continuing east by Skytrain, the next node is the City of New Westminster on the Fraser River:

It’s a city in transition, but again, they aren’t afraid to make big and bold—that is, tall and high-density—moves with their new buildings:

The 37-story triple tower project shown below, known as Plaza 88, is completely integrated with the New Westminster Skytrain station and bus terminal:

Imagine that instead of a huge surface parking lot and some scattered low-rise apartments and strip malls, there were half a dozen high-rise towers clustered around the Sound Transit LINK light rail station in Tukwila. That’s the difference between how the greater Vancouver region does things, and how the greater Seattle region does things.

And it’s why greater Vancouver will continue to be a more sustainable region for decades to come.

>>>

All photos by the author, taken on a dreary gray December day in 2013.

Will The New Mayor Inspire Seattle To Rise Above Fear Of Change?

Note: I was invited by Seattle Met magazine to contribute to a series of short essays offering advice to Seattle’s new mayor. It’s now on the stands in the January 2014 issue, and here’s the raw version of mine…

>>>

Seattle is on a roll. Great people want to be here. Great businesses want to be here. As human energy pours into Seattle, the one sure thing is change. And what the new mayor needs to do is lead Seattle in embracing that change, rather than fearing it.

Because buildings are so tangible, development is one of the most polarizing aspects of change in Seattle. And when people respond from the perspective of fear, all they can think about is how big new buildings are going to make things worse.

The alternative is to see Seattle’s prosperity and the development it induces as the phenomenal opportunity it actually is. With all the potential for growth in Seattle, the prospects have never been better for creating one of the most sustainable cities on the planet, while at the same time abating sprawl’s decimation of the greater region.

As with every human endeavor, development sometimes comes with warts. But if the fear-driven reaction is to attack developers, everyone will lose in the end. And those hit hardest will be the poor, because when demand for new housing outstrips supply prices skyrocket, and the result is a city accessible only to the wealthy—case in point, San Francisco.

The next major’s task is to inspire Seattleites to rise above fear of change, and channel their abundant passion and creativity into positive collaboration on development that will set a national example for how cities can grow in a way that benefits everyone.

>>>

Construction photo by Darick Chamberlin.

Why is the trend of decreasing auto use shown below happening in downtown Vancouver, BC, even as population and jobs have risen?

Because of this:

That is, lots of tall residential buildings. That is, density.

Vancouver BC is not afraid of height. They’ve been successfully weaving towers into their neighborhoods for decades, as on this quiet West End residential street:

Towers everywhere you turn:

Sleek towers:

Weird towers:

Shortish towers:

And they just keep building more:

And even with all that height, downtown Vancouver is an amazingly comfortable place to be a pedestrian, mainly because most of the towers are relatively slender, and there’s lot’s of space between them. All the urbanist Vancouver hype is well-deserved—the City’s urban form is truly unmatched.

Meanwhile, in the big city a couple hours south of the border, height is still a dirty word. And the result is not only squandered opportunities for density and all its sustainability benefits, but also a more oppressive urban form of chunky, squat buildings crammed in together.

Why is Seattle so afraid of height?

>>>

Source of Vancouver chart: Vancouver Transportation 2040. All photos by the author, taken in downtown Vancouver 12/11/13 — 12/13/13.

Getting Real About The Costs And Benefits Of Affordable Housing

One of the many complex facets of subsidized affordable housing is the question of where it should be located. Ideally, every neighborhood should maximize equitable access to opportunity by accommodating a complete and balanced spectrum of household incomes. But the conversation can’t end there, because getting real about that ideal means grappling with thorny cost versus benefit choices.

The first cost reality to consider is that the more expensive the neighborhood, the more subsidy it takes to provide an affordable housing unit—in many cases a lot more. As an example, according to the Seattle Office of Housing, the maximum rent for a 1-bedroom apartment affordable to a household earning 80 percent of area median income (AMI) is $1301 per month. In a typical Seattle neighborhood a new market-rate 1-bedroom might rent for let’s say $1400 per month, which means the required subsidy is about $100 per month. But in an expensive neighborhood such as South Lake Union (SLU) in Seattle, a 1-bedroom unit is more likely to rent for something like $1800, which translates to a subsidy of $500 per month. Assuming a 50-year commitment, for a $300,000 investment the City gets either five subsidized units in a typical neighborhood, or just one subsidized unit in SLU.