Grading the Green City: Applying LEED-ND to the Existing Built Environment

When NRDC, the Congress for the New Urbanism, and the US Green Building Council created the LEED for Neighborhood Development rating system, their aim was to rethink how development could address climate change, sprawl, and threats to human health. The overarching LEED platform had mainstreamed green building, and LEED-ND was an effort to expand its scope beyond the building shell for a more comprehensive standard of neighborhood sustainability.

Shaping the direction of future development is crucial to promoting livable communities in an expanding world. But what if, instead of looking ahead to future development, we used the LEED-ND criteria to evaluate the sustainability of the existing built environment?

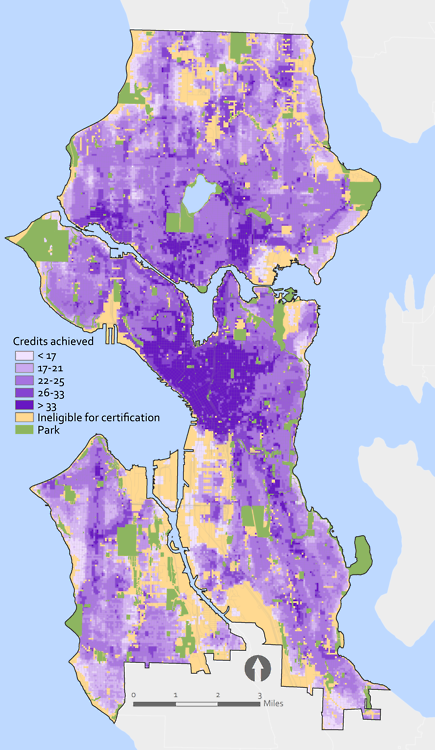

I developed a GIS methodology for applying the LEED-ND criteria to an entire city and scored Seattle as a case study. It’s purely theoretical, since certification is an option only for sites that have new construction. But there are important lessons in what we’ve already built. If an entire city or region is evaluated on the LEED-ND scorecard, we can better understand what places—that we already intimately know—best match the type of development that the USGBC wants to encourage (assuming that LEED-ND is a good proxy for a sustainable neighborhood).

From a GIS perspective, the specificity of the LEED-ND credits made things interesting. Some credits were simply not feasible to evaluate, either because the data were not available (like building façade details or energy and water use) or the credit can’t apply to an existing site (habitat restoration, for example). Sometimes I adapted the nuances of the credit to the data available. In short, my method used GIS data to evaluate whether any given point in the city meets or fails the specific requirements of each credit and then summed these data layers to determine the final score. I divided the city into a grid of one-acre sites—a fine enough resolution to produce a meaningful surface raster, but large enough that it resembles the scale of real-world projects. (For those interested, there’s more about my methodology here.)

Enough about the nitty gritty. Let’s get to the results. (Download a full summary poster pdf here, or view the poster image here.)

The suite of credits I evaluated account for about half of the total points available and emphasize walkability, transit access, parks and open space, income diversity, and residential density. Neighborhood qualities like mixed uses, a variety of housing typologies, and frequent bus service factor heavily in the final map. With this in mind, it’s no surprise that some of the areas scoring highest in my analysis were neighborhoods like University District, Ballard, Pike/Pine on Capitol Hill, Mount Baker, and the Downtown Central Business District. These are places where a mix of housing, businesses, shops, and public spaces encourages you to go by foot or bus instead of car—a pattern of development that can reduce per capita carbon emissions and sprawl while increasing physical activity and health.

Most of us are probably familiar with this narrative, as urban sustainability has become pretty mainstream in the past few years (thanks in part to LEED-ND). But using tools like GIS to visualize where that kind of development already exists, and what places might be well suited for a rating system like LEED-ND, has a lot of untapped potential. A developer interested in building a LEED-ND project could select a site that already fulfills many of the program’s spatial requirements. A planner can look at high-scoring neighborhoods and ask: Do we like these places? Is it fitting that this is what the USGBC is rewarding, or should we be encouraging something else? Most of all, this cursory survey of Seattle shows how valuable GIS can be in each step of the LEED-ND process. The more we can grease the wheels of this kind of development, the more we can produce neighborhoods that are equitable, encourage physical activity, and address the challenges of climate change and resource scarcity.

For more maps and information, check out gradingthegreencity.com.

>>>

Nick Welch is pursuing a Master’s in Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University in Medford, MA. His focus is on sustainability planning, neighborhood development, and geospatial analysis. Examples of his work can be found at nicolaswelch.com.