We Already Have The Tools To Meet Seattle’s Need For Affordable Housing

Concerns over rising housing prices in Seattle have once again provoked heated public debate over what to do about it. In response, City Council’s proposed solution for funding subsidized affordable housing is a so-called linkage fee—a extra tax on all new development based on the amount that’s built. As I have argued previously, the linkage fee has serious shortcomings and is likely to exacerbate the very problem it is intended to address by either increasing the cost of new housing, or slowing its production.

What most Seattle policymakers appear to be overlooking is that Seattle’s projected affordable housing needs could be met by simply strengthening existing, proven programs, without resorting to an untried, complicated linkage fee that is both unfair and counterproductive. The true solutions staring us all in the face are the Housing Levy and the Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE), combined with robust production of market housing that will help keep prices in check by absorbing demand.

What is Seattle’s need for affordable housing?

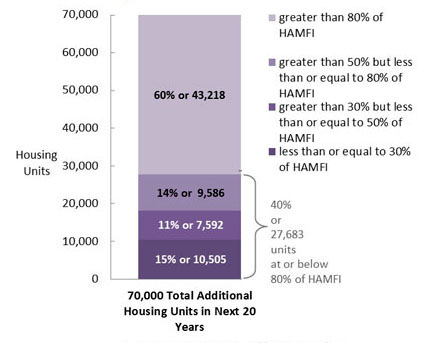

According to the Seattle Office of Housing, over the next 20 years there will be a demand for 28,000 new units of housing affordable to households with incomes at or below 80% of area median income (AMI). That’s equivalent to an annual average of 1400 units, or, to put it in perspective, about $350 million worth of new rentals per year. Separated by household income range, the Office of Housing’s projected average annual need is as follows:

- 0 – 30% AMI: 525 units/year

- 30 – 50% AMI: 380 units/year

- 50 – 80% AMI:Â 479 units/year

What do Seattle’s affordable housing programs produce?

Seattle’s current Housing Levy generates about $20 million per year from property taxes to fund affordable housing. During 2010 – 2013, Levy funds were applied to projects that have created an average of 417 units per year for households with incomes of 60% AMI and below. The Levy costs the owner of a median-value Seattle home $60 per year.

The MFTE offers a 12-year property tax exemption on multifamily buildings if they set aside at least 20 percent of the units for incomes in the range of 60-90% AMI. As of 2013 there were just over 3,000 MFTE units in active operation and another 1300 units approved. That corresponds to an average of 291 units created per year, though over the past two years the rate has been higher at about 700 – 800 per year. The tax exemption that enables the production of these affordable units corresponds to an additional annual tax impact of a mere $10 per median home.

Additional income-restricted units are produced by the Seattle Housing Authority using primarily federal funds, and by other non-profit affordable housing developers not relying on Housing Levy funding. The City of Seattle does not keep an inventory of these units, but they can be expected to make a significant contribution. For example, at Yesler Terrace the Seattle Housing Authority has plans to build 390 new units of housing for <60% AMI.

How affordable are Seattle’s market rentals?

The most current analysis available from the Office of Housing (2006-2010 data) shows that about three quarters of Seattle’s total rental units are affordable to a household with income of 80% AMI. Broken out by income range, the percentage of units affordable are as follows:

- 0 – 30% AMI:Â 11%

- 30 – 50% AMI:Â 22%

- 50 – 80% AMI:Â 42%

Because some households choose to rent units cheaper than what they can “afford” based on the standard formula, market housing that’s affordable still may not be available to lower income households. The Office of Housing data show that there is a surplus of over 7000 units affordable and available in the 50-80% income range, while there are deficits in the lower income ranges.

The Solution: Build on Success

The information presented above reveals that the combination of the Housing Levy, the MFTE, and existing affordable market rentals is already meeting a large portion of Seattle’s projected future need for affordable housing. For simplicity, let’s assume that over the next 20 years the City will need about 1000 units per year in the “low-income” range of 0 – 60 % AMI, and about 400 units per year in the “workforce” range of 60 – 80% AMI.

In recent years, Levy-funded projects have been producing two fifths of Seattle’s future low-income housing need. If the Levy was increased by 2.5 times, it could be expected to meet the entire need for 1000 units per year (assuming similar leveraging of other funding sources). That would translate to a tax of $150 per year for the median homeowner, or $13 per month. Factoring in the anticipated rate of low-income units produced without Levy funds, and the potential for affordable housing development on City-owned land, the necessary increase in the Levy would probably be closer to 2X than 2.5X.

That leaves the workforce housing need, which can can be readily met by a combination of the MFTE and existing market rentals. On average, the MFTE has been producing nearly three quarters of Seattle’s projected workforce housing need. Note also that these units are inclusive—that is, they are in the same building and neighborhood as the market units—and they come at a tiny cost to the average taxpayer. In short, the MFTE is a highly successful program. Two refinements that could improve it are an extension of the 12 year expiration, and easing requirements for applying it to existing housing and renovations.

The fact that over two fifths of Seattle’s total inventory of market rentals are affordable to 50 – 80% AMI clearly demonstrates that the private market can play a major role in meeting Seattle’s workforce housing need. And the way to keep the prices of older market rentals down is to maximize the production of new market housing, which absorbs demand from higher income people moving to Seattle. In contrast, a linkage fee is likely to slow market rate production and drive up prices of Seattle’s existing stock. Seattle’s workforce housing need could also be better supplied by the market if the City would remove overly restrictive regulations on accessory dwelling units and backyard cottages in single-family zones.

Share the Burden

A key advantage of the property tax-based approach described above is that it spreads the burden across all property owners, as opposed to a linkage fee that extracts only from the relatively small fraction of properties that redevelop. Owners of high value properties that won’t be redeveloped for decades—the half a billion dollar 76-story Columbia Center, for example—would contribute nothing to affordable housing through a linkage fee. With a property tax, owners of the most valuable properties pay the most.

In addition, when the burden is shared through a uniform property tax, the impact becomes relatively small on individual property owners—and the additional expense is a tiny fraction of what owners have been gaining in appreciation in recent years. On the market housing side, the cost to the City for encouraging private development is essentially zero, and new development enlarges the tax base.

In retrospect, Seattle has done a good job addressing affordable housing, and has effective subsidy programs already in place. San Francisco’s housing prices are still about 50% higher than Seattle’s, which has everything to do with the fact that Seattle has had a lot more private market housing development over recent decades.

Seattle has work to do to address affordable housing, but it’s not a crisis—yet. If we can keep cool heads and avoid politically driven, counterproductive quick fixes such as the linkage fee, we can succeed by sharing the burden and building on success.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban planner with VIA Architecture, a firm that consults to clients who may be impacted by a linkage fee.