New Housing Is Not The Enemy

When change occurs as rapidly as it has been in Seattle, misplaced blame runs rampant. And one of the most egregious examples is the contention that the construction of new housing is the cause of declining affordability—case in point, a coalition of Seattle neighborhood groups is currently advocating for a moratorium on new housing construction. But the reality in Seattle couldn’t be any more diametrically opposed: building housing at higher densities is actually a means to reduce the loss of existing low-cost housing.

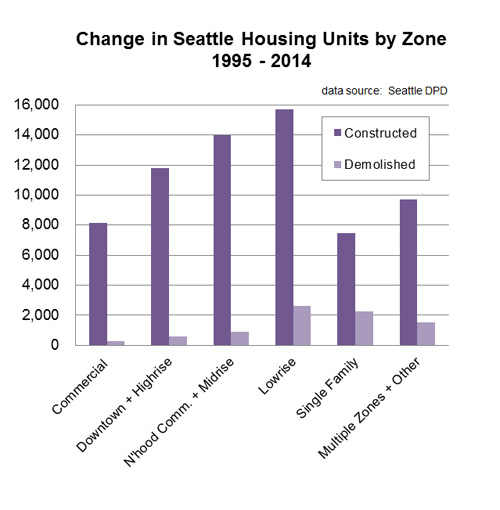

To understand why, start with the data. According to the Seattle Department of Planning and Development, from 1995 to 2014, 68,433 new housing units were built and 8,724 units were demolished. That corresponds to a ratio of eight, meaning development is staying way ahead of the game in terms of net increase in housing, which helps affordability across the board by absorbing demand.

Furthermore, a nontrivial chunk of the demolishing likely had nothing to to do with housing redevelopment—the 8,724 includes units demolished for any reason, not just to make way for new housing. During 1996 to 2005 (newer data unavailable), over 25 million square feet of non-residential floorspace was developed in Seattle, and it’s reasonable to assume that some of that resulted in demolished housing. It is also reasonable to assume that some housing was demolished simply because the buildings had aged beyond their lifespan.*

While there is no question that housing development results in a lot more housing units gained than lost, it is also true that new housing is typically more expensive to rent or buy than old housing. And if new housing actually does take out existing housing, then the new units will likely be more expensive than the units that were lost. First, as alluded to above, to some extent this process is normal and cannot be avoided, because housing ages and eventually has to be replaced.

But second, and more importantly, it is a logical fallacy to conclude from this that housing development is inherently bad for affordability. Accurately assessing the impact requires a comparison to what would have happened absent the new housing. And in a high demand market like Seattle, the result would be greater competition for a limited supply of existing housing, which would drive up the rents, likely leading to renovation to meet demand for higher quality units. In other words, saving the existing units would not preserve their affordability for very long, and in fact, the system-wide effect would be a net loss in affordability caused by suppressed supply.

Looking at the housing data by zone in the above chart, it is clear that, on average, higher density development results in fewer units lost for every unit built. Given the basic math involved, that shouldn’t come as a surprise. The more housing units that get put on a given amount of land, the less likely it will be that existing housing will need to be demolished to make space for it. As can be observed through0ut Seattle,** most high density housing projects replace parking lots or spent commercial buildings, and not much, if any, housing.

Given the objective reality, it is remarkable how high density development is still so often a prime target of ire from people concerned about the preservation of affordable housing. Instead of pushing for further restrictions and fees that impede high density development and make it more expensive, these folks ought to be advocating for policies that promote building to the highest densities wherever possible. The same goes if the concern is about preservation of open space, tree canopy, or streams. Put simply, when we build up, there’s more room left over in the City (and the region) for other things we value.

In an analogous policy disconnect, high density projects are also the City’s biggest target for the extraction of development fees to offset their supposed “impacts.” But as the City’s own data show, the higher the density, the lower the impact on existing housing. A more sensible policy approach would place the tax burden of subsidizing affordable housing on low density properties, because inefficient land use is one of the root causes of Seattle’s affordability challenges.

The City’s ultimate example of misplaced blame is South Lake Union (SLU), which has long been a lightning rod for denunciation regarding affordable housing and gentrification. And last year SLU became the first neighborhood to be subjected to the City’s increased Incentive Zoning fees that are used to fund affordable housing. But guess what: From 2005 to 2014 (1995-2004 data were not parsed) there were 2,132 housing units built or permitted in the SLU zones, and only six housing units demolished. Not to mention the numerous subsidized affordable housing projects recently built in the neighborhood. It’s as if the City is intent on punishing the very places where things are being done right.

Lastly, none of this is saying that preserving existing buildings for affordable housing isn’t one of many potential strategies that the City policymakers should be exploring. However, we should not expect that the significant cost for the necessary subsidies can or should or be borne by a property owner who happens to own an old building. If the City wants buildings preserved to help meet affordable housing goals, then the City as a whole should step up and pay for it, and stop misplacing blame on housing development, which is actually part of the solution.

>>>

*For a quick thought experiment, assume that housing has a 100-year lifespan, and that Seattle built 300,000 housing units over 100 years and then stopped. At that point, the City would start to lose 3,000 units per year simply due to the lifespan of the buildings. For comparison, between 1995 and 2014, Seattle lost an average of 459 housing units per year to demolition.

**In this King5 news video, “monster” housing developments are vilified for causing loss of affordable housing, but the four projects shown that I could identify appear to have displaced a grand total of one housing unit!

Â