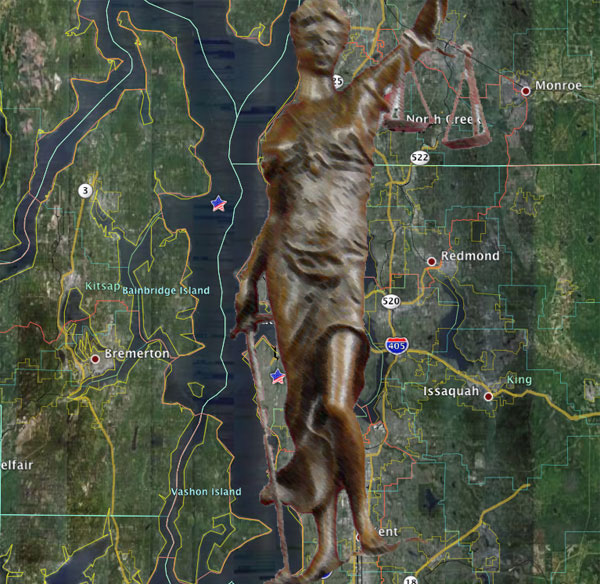

The Just Metropolis

< Image by the author >

Metropolitan areas with strong systems of regional governance are more equitable than those without. The basic premise is that in fragmented regions, where little or no sharing of tax revenue occurs, municipal corporations compete with each other to avoid negative spillover effects, and to reap the benefits of positive ones. The classic example is a newly incorporated suburb next to an established urban center with plentiful amenities and employment. The residents of the new suburb don’t have to pay the cost for maintaining infrastructure and urban amenities that make city vibrant, attractive and successful, yet they can still access them. It’s a bit like living next to a golf course and slipping on to play the back nine without paying greens fees. The tax base of the city shrinks as people with means relocate to the suburb with lower property taxes. The core city enters a spiral of decline, and citizens experience savage inequalities in education, opportunity, and health.

Reality is more complicated than my example, but the lesson rings true: systemic injustices result when legislative and taxation boundaries don’t match functional boundaries. Those who can’t afford to move to take advantage of the positive external benefits, end up on the losing side. If fairness is something we value as a society, then we should embrace a regional approach to funding and managing the amenities that we all enjoy and the vital infrastructure our success depends on.

>>>

Japhet koteen is a planning and development consultant in Seattle. He specializes in regionalism, energy systems, placemaking and cheese.

< Daniel Friedman FAIA, Dean of the University of Washington’s College of Built Environments, Provost Lecture: City in Five Acts: Interpreting Urban Experience, April 21, 2010 >

Despite Seattle’s vital role in driving our economy, it continues to lose funding and support, thereby threatening our region’s prosperity.  This is due to the most pressing problem facing the Puget Sound region today:  Seattle’s own political weakness as a regional and statewide player.

According to CEOs for Cities, “cities constitute 30-40% of the assets and productivity in major metropolitan areas†and Seattle is no different.  That means when the UW loses funding, when our transit system is crippled, when our public schools fail, when our arts community is marginalized, our entire region loses.  We lose talent, we lose growth, and we lose one of most competitive advantages: innovation.  These investments in Seattle do not stop at Seattle’s borders.

Instead of apologizing for our funding needs, we should be boosters for them. (Can we have dedicated, rapid transit through a watery, hill terrain?  Yes we can and not only that, we have to.) We can take our entrepreneurial spirit— after all we are the land of the Gold Rush, the start-up, the new band, the large company that came up from scratch—and use it to create the kind of region we all aspire to.

This isn’t the old City versus the suburbs saw; this is Seattle recognizing its leadership position and utilizing it effectively:  Actively listening, inspiring a shared vision, and modeling the way.  We must be persuasive and compelling, not just large.  Then Seattle can truly affect change for a more sustainable future for all.

>>>

Stephanie Pure is the External Relations Director at AIA Seattle, a Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, and the above are her personal views.

C200: Regions — To Live In

The hope of the city lies outside itself. Focus your attention on the cities—in which more than half of us live—and the future is dismal. But lay aside the magnifying glass which reveals, for example, the hopelessness of Broadway and Forty-second Street, take up a reducing glass and look at the entire region in which New York lies. The city falls into focus. Forests in the hill-counties, water-power in the mid-state valleys, farmland in Connecticut, cranberry bogs in New Jersey, enter the picture. To think of all these acres as merely tributary to New York, to trace and strengthen the lines of the web in which the spider-city sits unchallenged, is again to miss the clue. But to think of the region as a whole and the city merely as one of its parts—that may hold promise.

>>>

Lewis Mumford is dead. He wrote the above 86 years ago. It is the opening paragraph of “Regions — To Live In,” published in Survey Graphic, LIV ( May 1, 1925). That issue featured contributions from several of the visionaries behind the Regional Plan Association, established in 1922. Alas, we didn’t pay much attention to those ideas during the most of the 20th Century, though in recent decades regionalism has seen a resurgence.

C200: Our Fractured Metropolis

“Puget Sound is one of the most beautiful places in the world. Its contribution to Washington’s economy, environment, and special quality of life cannot begin to be calculated.†(Warren G. Magnuson, May 7, 1989).

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the problem of cleaning up Puget Sound—the second largest marine estuary in the United States. From the land, the sea still holds much beauty. Yet it is the single biggest, most intractable environment challenge facing Washington State. The iconic Chinook Salmon, along with 20 other marine animals are endangered, dwindling pods of Orca whales are among the most PCB contaminated mammals on Earth, and entire marine ecosystems are dying off. Millions of pounds of toxic pollution flow into Puget Sound every year—mostly from storm water run-off and combined sewer overflows, carrying deadly poisonous chemicals from urban areas to the sea.

In one of the “greenest†states in the country, why can’t we stop this ongoing pollution? Puget Sound basin, home to 4.4 million people, is bordered by 90 cities and towns and an unfathomable maze of overlapping jurisdictions and regulatory agencies. No one agency controls, and as Kathy Fletcher, founder and retiring director of People for Puget Sound says, “our biggest challenge now, is the fragmentation of decision-making and lack of enforcement of existing regulations.â€

It’s been over three decades since Senator Warren G. Magnuson warned of a

looming “environmental catastrophe†facing Puget Sound. Today, it’s not oil tankers but urbanization that is the biggest threat to the health of the Sound. If we allow Puget Sound to atrophy, so too, will our economy, and our way of life in the Northwest. By 2040, the region is expected to grow nearly two million more people. Puget’s sound’s persistent ill health is symptomatic of our fractured metropolis.

>>>

Peter Steinbrueck, FAIA, is principal of Steinbrueck Urban Strategies and former Seattle City Councilmember.

C200: Not Your Grandmother’s Cleveland

Those of us on the side of civilization—which does not include everybody—understand the value and function of cities. But it’s important to recognize that the character, scale, and disposition of urban life is entering a new phase: contraction. Contrary to the fantasies of many, I believe our cities will have to get smaller, denser, and better organized around their historic centers and waterfronts in order to thrive in an energy-scarce future.

Contrary also to figures like Ed Glaeser at Harvard (author of the new tome “Triumph of the City”), we’re done with skyscrapers and megastructures, and not just for energy reasons, but because they will never be renovated. Our energy scarcity will be matched by a capital scarcity and, very probably, a scarcity of the very high-tech fabricated modular materials we had gotten used to building in. Cities cannot be made out of structures with no hope of adaptive re-use – so we’re going to have to come up with a better plan than the mistaken “green” proposal to stack everybody up in towers.

That better plan consists of traditional urbanism, based on the walkable neighborhood (or district), and buildings scaled appropriately to the resource realities of the years to come.

Personally, I believe the contraction process will be agonizing for our giant metroplex cities, and that the “action” will shift back to our smaller cities and small towns – especially to places that exist in relation to local food production, navigable waterways, and water power.

>>>

James Howard Kunstler is the author of The Long Emergency, The Geography of Nowhere, and 12 other books, including nine novels.

C200: 1. Art=Sustainability; 2. Art=Money

1. Art = Sustainability

Art is core to sustainability. When people sing, dance or act, they draw upon resources within themselves to tell their own stories. Humans are first and foremost storytellers, and this is why advertising is so effective at urging us to consume material goods. Yet artists’ remain immune to the hawking – eschewing lives of perceived security in order to pursue lives of creativity. In the process, as the myth of the “starving artist†reflects, artists learn to be self-sustaining.

If Seattle is to create a sustainable society, we need to shift away from the consumption of material resources and towards the creation of cultural resources. Artists can show us how.

Rarely does a city of Seattle’s size have so many major arts institutions, and likewise, such a thriving independent scene. Seattle’s theatre, dance, music, film, literary art and heritage communities are all nationally renowned. How this came to be is a complex story, but one thread is tied to the creation of the field of Public Art.

In the late 1970’s, King County and Seattle launched Public Art programs that allowed artists to contribute not just objects, but ideas. In doing so, Seattle became a place where artists could receive public funding to create meaningful work, and over time, more and more artists moved to our region creating a critical mass of thinkers. Today, Seattle’s artists are encouraged to take a seat at the table to discuss public policy, and many of our region’s Public Art projects interact with infrastructure, wetlands and other systems.

Art resists interpretation, but if I had to define the concerns of contemporary artists, I would emphasize experiences, meaning, relationships and uncertainty. Without coincidence, these are also the hallmarks of sustainability.

2. Art = Money

Shuffled beneath the “starving artist†myth is the reality that local government funding of the arts is core to our region’s success. In 1971 – when the unemployment rate was 17.5% and Boeing had laid off 65% of its workforce – the Seattle Arts Commission was founded. The “% for Public Art”  programs referenced above soon followed. Yet the “1% for Art†nomenclature indicates a much higher funding level than arts commissions actually receive. Even adding in performing arts, heritage and granting programs, funding levels for arts agencies fall well below 1% of total government expenditures.

“Orthodox micro-economists dismiss concern for artists’ relatively low earnings given their high educational attainment as simply a case of market over-supply,†explains economist Anne Markusen. “In contrast, scientists who are highly subsidized both in higher education and through government research funding . . . are simply more highly valued in our political system at present. . . But vis-à -vis stimulus, artists turn economic orthodoxy on its head. Compared to most other groups of workers, artists are more apt to spend what they make rapidly and on other goods and services in the local economy. . . [Artists’] creativity drives cultural industries—media, publishing, advertising, music, and tourism—that are among the most important US exporters.â€

Reviewing a recent Americans for the Arts study, the Urban Land Institute highlights the fact that the arts generate nearly “$30 billion in revenue for federal, state, and local governments every year. When one considers that these three levels of government spend less than $4 billion annually to support the arts, one cannot help but be impressed with the more than seven-to-one leverage.†Locally, a recent ArtsFund study reveals that culture in King County generates $1.75 billion dollars in economic activity; employs more than 29,000 people; and generates nearly $80 million dollars in local tax revenue.

Data filled arguments are required by our modern society to validate expenditures, making economic arguments the most readily available. Yet the 7:1 economic return cited above is indicative of a much more vibrant and complex social structure. Art contributes to environmental sustainability, education, social justice, public health, public safety and quality of life. This menu of benefits is so compelling that we sometimes forget to proclaim the obvious: when we invest in the arts, we receive art.

Art stimulates the economy. Art stimulates humanity.

>>>

Cheryl dos Remedios is an artist, activist and public art administrator. She currently serves on the Great City Board, the Arboretum Foundation Board, the Rainier Beach Neighborhood Advisory Committee and the Port of Seattle Art Oversight Committee. She is also organizing aLIVe: a Low Impact Vehicle exploration and Save Our Soul {SOS} Seattle.

>>>

Image Credits: The Herbert Bayer Earthwork was commissioned as part of King County’s groundbreaking Earthworks: Land Reclamation as Sculpture symposium in 1979. As staff to the Kent Arts Commission, the author organized the Earthworks 25th Anniversary Celebration in partnership with 4Culture. Brice Maryman’s Chromatic Levy (upper image) traversed Mill Creek, while choreographer/dancer Alex Martin’s site specific performance The Daylight (lower image) literally moved the audience in and out of the steep and curving contours of the park. Pictured (L to R): Sarah Parton, Liz Cortez, Sarah Shira and Monica Mata Gilliam.

C200: Growing Well

After more than 30 years in local government, 22 as an elected official, this past year has been one of discovery for me. Living in Boston and New York for extended periods helped me learn perspective—and to appreciate Seattle even more.

Teaching at Harvard University last “Spring†gave me a chance to sample Boston’s iconic “T†(and cannoli) and learn how climate, history and universities shape a city. I had never before seen a frozen river.

Representing the US at the UN General Assembly last Fall put me in the heart of Manhattan for almost four months. The scale was deeply unsettling at first but became more comfortable as I learned to enjoy the kinetic pace and remarkable diversity of offerings. (Ol’ Blue Eyes was right about those “little town bluesâ€, they melted away.)

Our City is now home to 608,660 souls (2010 Census). Seattle is growing, and growing up. We are a center for innovation and we are embracing our place as the vibrant heart of a prosperous region.

This is important for a host of reasons: social, economic and environmental (think climate protection); but the challenge is to grow in the right way.

Can we preserve the things that make Seattle special while embracing a diverse, dynamic and low-carbon future?

Yes we can!

>>>

Greg Nickels is the former Mayor of Seattle.

C200: Cities: The Cradle Of Degeneracy

Sub Pop was largely designed by Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman in the mid-eighties so that they could release music by Soundgarden. They also wanted to make records for Green River, Mudhoney and Nirvana. Bruce and Jon both lived in Seattle, then a beautiful but quiet city with a gritty edge. In order to make their dreams (of furthering degenerate activity and creating a frightfully unwieldy nightlife in the city) come true, they needed to be in a city that was big enough to create a small army of hellions (preferably consisting of drunks, drug addicts and/or mentally unstable individuals), but a city that was also small enough for that army to have an impact.  Seattle became the epicenter of “grungeâ€, a cultural venereal disease with no known cure that Sub Pop was proud to spread globally. This natural disaster couldn’t have happened anywhere else nor could it happen today. Seattle was the right place and the mid-eighties was the right time for the shit to hit the fan.

>>>

Megan Jasper is Executive VP of Sub Pop Records.

C200: Busting Barriers and Achieving the Urban Balance

< The Seattle skyline from Lake Union; image: Chuck Wolfe >

Cities are the focal point of interaction between human and natural systems and are the laboratories of how best to live—call it “achieving the urban balanceâ€. We all have pictures of what that balance should look like, both visually and in terms of environmental impact.

Of the many human systems that contribute to the urban balance, land use regulation plays an important part, as the consensus constitution for forms of urban development going forward. Traditional land use tools need to evolve in order to assure a sustainable urban balance and to better wed land use and transportation issues.

The question is how to achieve balance amid the implementation barriers common to presentation of new urban land use approaches.

Many examples of innovation exist, from form-based codes to sustainable development regulations, all designed to move away from increasingly disfavored separation of zoning uses, to approaches which facilitate less reliance on the automobile where possible, encourage forms of transportation which emphasize human health, as well as more clearly enable sustainable development tools.

There are positive signs in the Puget Sound region. For example, in the time since a report identified regulatory, political and fiscal barriers to transit oriented and urban center development in 2009, initiatives at the local and state levels have turned renewed attention towards issues of concern in the transit and infrastructure-funding arenas. Municipalities have experimented with types of zoning which focus more on look, feel and mixed use than hard and fast, traditional techniques. In addition, last Fall, on behalf of the region, the Puget Sound Regional Council was awarded $5 million in the form of a federal Sustainable Communities grant to enhance planning for urban centers along transit corridors.

However, fallout from recent midterm elections has illustrated the risks of backsliding—a reminder that “achieving the urban balance†and related inventories of best practices and regulatory enactments are more often than not inherently political—and often fall short of lofty goals.

Backsliding can be offset by “stay the course†non-governmental organizations, professionals and citizens who will survive political change, and who will continue to parlay an evolutionary urban agenda.

Let’s both grow the toolbox, and keep it open.

>>>

Charles R. (Chuck) Wolfe, M.R.P., J.D. is an environmental and land use attorney in Seattle, and an Affiliate Associate Professor of Urban Design and Planning at the University of Washington. He writes for several publications, including The Huffington Post and Crosscut, and blogs at myurbanist.

C200: The Revolution Will Not Be Facebooked

We live in an era in which it is easy to telecommute from any sylvan spot, but our cities are more important than ever. America’s three largest metropolitan areas, with only thirteen percent of our population, collectively produce eighteen percent of national output. Cities continue to be so important because globalization and new technologies have increased the returns to being smart, and we are a social species that gets smart by being around smart people. Cities help make that happen.

Cities have long enabled chains of invention from Athenian philosophy to Ford’s Model Ts to Facebook. The skyscraper, for example, was collectively developed by a cadre of brilliant architects brought together by Chicago after a great fire. Urban innovation will help us meet the enormous challenges that our planet still faces, like developing world poverty and the risks associated with climate change. High density urban living can also reduce energy use and carbon emissions.

In 2011, the power of cities is most obvious in the Middle East, where urban uprisings have forced autocrats to abdicate. We don’t know what will happen in these countries, but these events reminds that even a Facebook Revolution takes a city to succeed.

>>>

Edward Glaeser is a professor of economics at Harvard University and a senior fellow of the Manhattan Institute. He is the author of, most recently, The Triumph of the City.

C200: Sidewalks as Yellow Brick Roads to Health

< The author attempts a "safe walk" on sidewalkless N. 130th St, c. 2010 >

>>>

Richard L. Dyksterhuis, 83, is a retired Seattle school teacher and principal, and has been active for improved infrastructure and increased open and park spaces in the Bitter Lake-Broadview area for five years.

There’s been some Jane Jacobs-bashing lately in the more-urbany-than-thou circles in which I sometimes travel, and I just won’t stand for it. Respected colleagues have been complaining that Jacobs did us a disservice by failing to prescribe policy, but that wasn’t her M.O, and it’s not as if we’ve excelled at picking up where she left off. Now we have Ed Glaeser’s recent suggestion that Jacob’s ideas about preservation were naïve, and that she didn’t really “get†density, or at least not the skyscraper version that he subscribes to.

Jacob’s work, or at least my reading of it, celebrates fine urban grain and repurposed buildings not for their static qualities but as necessary mediators of change. Jacobs didn’t say that buildings need to be short instead of tall or old instead of new, but rather that we need a diversity of them in order for new residents and businesses to get a foothold and move up the ladder of social and economic development. She promoted an incrementalist approach to densification because the economics of colossal new projects make them “inherently inefficient for sheltering wide ranges of cultural, population, and business diversity.†She exposed the incubator capacity of granular neighborhoods, and the multiple reasons why small independently-owned companies (the ones with the largest local multiplier effect) don’t tend to locate in cavernous downtowns.

She also pointed out that bigger projects mean more egregious errors. Design is subjective, but we can probably all agree that big-block sites do not, as a rule, seem to inspire the architecture profession’s best work. Unlike skinny infill, the big shiny mistakes aren’t easily absorbed into our existing urban fabric. And when they replace older pieces of granular city that have real value in terms of both function and identity, for newcomers and old-timers alike, we shouldn’t be surprised if density becomes a dirty word.

There is a temporal quality to the production of sustainable urban form that is perhaps difficult for macro-economists and policy-makers to recognize. It isn’t reflected in static measures of square footage or units or building heights, but rather in a slow but steady turning of the dial toward a higher intensity of users, connection and access, resource efficiency, character and identity, and choices.  Jane would no doubt remind us that the critical issue isn’t what density should look like, or how much is enough, but rather how we insert it more surgically and gracefully.

< Two views of 16th Street, Denver; photos: Matthew Blackett, Google Streets >

>>>

Liz Dunn is the principal of Dunn & Hobbes, LLC, a developer of adaptive reuse and small-scale infill projects in Seattle, and is currently the Consulting Director of the National Trust’s Preservation Green Lab.

C200: Cityants

< Looking north on 1st Ave, downtown Seattle; photo: Dan Bertolet >

Ants are very different from humans. To begin with, they are advanced eusocial animals, where as humans, along with many wasp types, have attained a eusociality that’s only primitive. Eusociality proper is attained when the social organization of a species is biological—army ants have big heads and pinchers, worker ants do not reproduce, only a queen can live long and generate eggs. Humans are highly social and have an exceptional division of labor (exceptional to other primates), but the organization of our societies is not biological but cultural. Under normal conditions, an individual in a human society has the choice to join the army, work on a construction site or raise the young. Also, and again under normal conditions, any female human can reproduce. Ant societies have no males.

The reason why we often compare humans with ants is because human cities converge with ant colonies. A convergence in evolutionary biology is when two completely different species meet the same problem with the same answer. The wings of a bat and the wings of a bird are an example of a convergence. The wings of a bat did not descend from the wings of bird—if such were the case, then the two types of wings would be analogical rather than homological. The human city converges with an ant colony; their resemblance results from the fact that they are similar answers to the similar problems: super sociality (food storage and distribution, garage collection and disposal, transportation networks, ventilation systems).

In the book Ant at Work: How an Insect Society Is Organized, Deborah Gordon describes a remarkable discovery concerning the behavior of aging ant colonies. Old ant colonies do not behave the same as young ones. Even if the population and composition of an old colony is the same as that of a young one (an ant in the species she studied, the harvester ants of Arizona, lives for about a year), they do things very differently. Meaning, it’s as if the colony has a mind of its own, a mind and personality that’s independent of its own composition—many interacting ants.

Gordon’s discovery naturally points our thinking to the human city. From a history of human interactions might there emerge the personality of the city? A personality that is the city itself and has nothing to with the composition of the population it contains? Even if the composition of an old city like Rome were the same as that of a new city like Seattle, they would not behave, act, respond to problems in the same way. The old city behaves like an old person; the young one like a young person. When Nas rapped about a “NY State of Mind,†what he had in mind was the state of mind a city sets in a person. In the light of Gordon’s discovery, we can also think of a city as having its own state of mind.

>>>

Charles Mudede is a filmmaker and also associate editor at The Stranger.

C200: Resilience and Self-Sufficiency

< Rendering of the Bullitt Foundation's Cascadia Center that has been designed to meet the Living Building Challenge - click image to enlarge >

First made possible 5,000 years ago by rural agricultural surpluses, cities ballooned in the 19th century with the harnessing of fossil energy. Expansion, of course, brought problems. The world’s largest cities greatly exceed nature’s ability to absorb their pollutants, and they appear to be approaching, if not exceeding, the limits of what can be successfully governed.  Today, cities concentrate both the fruits and the detritus of human activity: commercial products, trash, art, sewage, political power, knowledge. . . .  We love their power and excitement, but we drown in their garbage.

Still cities keep growing larger—a trend that most specialists project to continue for the next century, as more and more youngsters desert the countryside for the better jobs and services of the city. For better and worse, cities have become the ecosystems of choice for human beings.

But cities are different from other ecosystems. Other ecosystems capture sunlight to produce essentially all of the usable energy (food) that keeps them working. Cities, on the other hand, rely on the countryside for food, and they depend on vast fragile networks of pipelines, power lines, and shipping lanes for their energy.

In a world that is vulnerable to acts of god, wars, terrorism, revolutions — not to mention the blundering ineptitude of fools who are foolish enough to thwart even the most “foolproof†safety systems — there is a case to be made for cities to strive for some level of self-sufficiency.

Most cities will never be able to produce all the food, energy, and water they desire within their own city limits. Yet they can put solar-electric panels on rooftops, create community gardens, and collect rain water in cisterns before it flushes away in storm sewers. They can recycle all their trash and compost all their organic matter to fertilize those urban gardens.

By engaging in such efforts, cities will spend their purchasing power close to home instead of in faraway places. And when big disruptions inevitably occur, the somewhat-self-sufficient city will be prepared to handle them with resilience and fortitude.

>>>

Denis Hayes promotes healthy human ecosystems as President of the Bullitt Foundation.