C200: Embrace Change

In order to remain prosperous, relevant and successful in an increasingly global world, cities must constantly adapt socially, economically, and physically. To paraphrase the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, the only constant in life is change. Humans have known this for thousands of years. So why does the prospect of change in our city—Seattle—and its neighborhoods provoke so much anxiety and ultimately counterproductive resistance?

The extension of a bike path results in a law suit, and proposed neighborhood up-zones near billion dollar transit investments are fought vehemently, resulting in vacant lots and boarded up houses rather than much needed urban housing. Too often, vocal opponents with targeted issues are allowed to dominate our public dialogue, and the city as a whole suffers.

The point is not that all change is good. Clearly, there are choices to be made. However, we should recognize that not only is change inevitable, in many cases it is a direct result of Seattle’s continued growth, vitality and success. There is always room for intelligent debate about what form change takes, but to simply wish for the city to remain as it is (or return to what it was) is both unrealistic and a recipe for mediocrity and a slow civic death.

We live in a city where people choose to move to attend college or start a career, a family, or a company. Plenty of other cities, like Detroit or Cleveland, would love to have our problems. Rather than expend our collective civic energy trying to prevent change, we should embrace our area’s growth and evolution and direct our energy towards becoming the most successful 21st Century city possible.

>>>

Gabriel Grant is a Vice President at HAL Real Estate Investments and Allegra Calder is a Senior Policy Analyst at Berk and Associates.

C200: Why Cities Don’t Matter

< People matter in Strøget, Copenhagen's Pedestrian Street; photo by the author >

Asking why cities matter is asking the wrong question. If cities mattered post-apocalypse movies and the great television series, “Cities After People†would have very different images of cities. What matters is not cities but people. A city street full of all the right elements—interesting buildings, vibrant storefronts, excellent bicycling infrastructure, great pedestrian only streets, super-energy efficient systems, etc, feels dead and cold without life—particularly without people.

The reason to care about cities is to care about ourselves—our happiness, our health, our children, our grandchildren. When we are inefficient with how we manage and use energy, when we pollute, or create the circumstances that creates unpredictable and more severe weather, when we insist that a great deal of a person’s personal resources must go to expensive housing and cars because we don’t have alternatives, we compromise our happiness and health and we compromise that potential for our kids and grandkids. Making better cities, cities that increase the quality of life for people while reducing resources and improving the environment (i-SUSTAIN’s mission) is fundamentally selfish.

Be selfish—because you matter.

>>>

Patricia Chase, President of i-SUSTAIN, is an urbanist who has spent 10 years researching and sharing global best practices in urban sustainability.

C200 (x4): Not “global warming†but planetary destabilization: What’s to be done?

Climate destabilization is not just another issue on a long list of vexing problems, but the linchpin issue, that properly handled would lessen many other problems including national security, balance of payments, economic recovery, economic justice and public health.

We need a far-reaching national climate and energy policy executed with wartime urgency. But too much money in politics, media dedicated to entertainment, multiple leadership failures, too much power in the hands of Senators representing more acres and cows than people add up to a system rigged to prevent solutions to public problems and seemingly incapable of repairing itself.

With no prospect for meaningful Federal climate and energy legislation anytime soon, however, what’s to be done? The short answer is that, whatever the prospects, we must keep pushing on every front to: change Federal and state policies, transform the economy, improve public understanding of science, engage churches and civic organizations, reform private institutions, and change our own behavior. But we might also take a page from the Tea Party movement and begin a fierce grass-roots commotion of our own—one powered by sunlight and science.

As one example, Oberlin College and the City of Oberlin have joined to launch the Oberlin Project. We have four goals: (1) rebuild a 13- acre block in the downtown to U.S. Green Building Platinum Standards as a driver for economic revitalization; (2) quickly transition to carbon neutrality; (3) develop a 20,000 acre greenbelt to revive local farming and forestry; and (4) do all of the above as a part of an unique educational venture that joins the public schools, Oberlin College, a community college, and a vocational educational school. Ten community teams are working on strategic issues such as energy, public policy, finance, community, economic development, and education. The aim is “full-spectrum sustainability†in which the parts reinforce the resilience and prosperity of the whole. Beyond reducing our climate “footprint†and building a more durable economy, the Project will also improve our security.

As one example, Oberlin College and the City of Oberlin have joined to launch the Oberlin Project. We have four goals: (1) rebuild a 13- acre block in the downtown to U.S. Green Building Platinum Standards as a driver for economic revitalization; (2) quickly transition to carbon neutrality; (3) develop a 20,000 acre greenbelt to revive local farming and forestry; and (4) do all of the above as a part of an unique educational venture that joins the public schools, Oberlin College, a community college, and a vocational educational school. Ten community teams are working on strategic issues such as energy, public policy, finance, community, economic development, and education. The aim is “full-spectrum sustainability†in which the parts reinforce the resilience and prosperity of the whole. Beyond reducing our climate “footprint†and building a more durable economy, the Project will also improve our security.

If true security means safety and access to food, water, energy, shelter, health, and livelihood—Americans have never been so vulnerable. Beyond traditional security challenges, we must now reckon with terrorism (homegrown and foreign), a “perfect storm†of food shortages, water scarcity, expensive oil, the multiple effects of climate destabilization, and “black swan†events such as the recent tsunami and nuclear crisis in Japan or the financial collapse of 2008. The upshot, in one analyst’s words, is that “we must squarely face the awful fact that our security will become ever more perilous.â€

We must also face the fact that no government on its own can protect its people and that citizens, neighborhoods, communities, towns, cities, regions, and corporations will have to do far more to ensure reliable access to food, energy, clean water, shelter, and economic development in the decades ahead. This is not to argue against Federal policy changes to promote sustainable development, reform the tax system, deploy clean energy, and improve public transportation—things that can best be done or only done by the Federal government. But communities will have to carry much more of the burden than heretofore.

Sustainability must become the domestic and strategic imperative for the twenty-first century. Its chief characteristic is resilience—a concept long familiar to engineers, mathematicians, ecologists, designers, and military planners—which means the capacity of the system to “absorb disturbance; to undergo change and still retain essentially the same function, structure, and feedbacks.†Resilience is a design strategy that aims to reduce vulnerabilities often by shortening supply lines, bolstering local capacity, and solving for deeper patterns of dependence and disability. The less resilient the country, the more military power is needed to protect its far-flung interests and client states hence the greater the likelihood of wars fought for oil, water, food, and materials. But resilient societies need not send their young to fight and die in far-away battlefields, nor do they need to heat themselves into oblivion.

A revolution in the design of resilient systems has been quietly building momentum for nearly half a century. It includes dramatic changes in architecture, solar technology, whole systems engineering, ‘cradle to cradle’ manufacturing, and smarter growth and transportation systems. Taken to its conclusion, ecological design would radically improve our security, environment, economy, health and strengthen communities while reducing our vulnerability.

National security is too important to be left solely to the generals, defense contractors, TV pundits, and tub thumping politicians in Washington. It will be necessary for neighborhoods, communities, towns, cities, and regions to improve their resilience and security by their own initiative, ingenuity, and foresight. The Oberlin Project is one example, but there are many others at different scales and in different regions. We have begun to join many of these into a “national sustainability network of sites, cities, and projects†which aims to improve local and regional resilience and prosperity. Remove the word “national†and imagine a global network of transition towns, cities, regions, and organizations—a solar powered renaissance of local capability, independence, culture, and real security. Imagine a world, someday, where no child need fear violence, hunger, thirst, poverty, ignorance, homelessness, or heat and storms beyond imagining.

>>>

David W. Orr is the Paul Sears Distinguished Professor of Environmental Studies and Politics the Special Assistant to the President of Oberlin College, and a James Marsh Professor at the University of Vermont. Orr is the recipient of five honorary degrees and other awards including The Millennium Leadership Award from Global Green, the Bioneers Award and the National Wildlife Federation Leadership Award. He has lectured at hundreds of colleges and universities throughout the U.S. and Europe. Dr. Orr will be speaking at Town Hall Seattle this Thursday April 21, 6 – 7:30 p.m.

C200: The Public Realm

One of the things that struck me most about Hong Kong is just how active and vibrant the public realm was. Everywhere you went, there were people out and about. Meals were eaten in open air cafes, business was conducted in the streets, commercial activity spilled out of shop fronts onto sidewalks and streets, and all of this contributed to a feeling of vibrancy that is all too often absent from U.S. city streets.

It seems like the public realm is where most people in Hong Kong spend the majority of their time. Not just using the public realm to move from point A to point B, but being in the public realm. Unlike in the States, where we more often than not use the public realm to move between destinations, in Hong Kong, the public realm seemed to be the destination.

That being said, amidst the bustling often-chaotic city life, there are also beautiful, unassuming moments of quiet and serenity. Evidence of people carving out a bit of the private in the public realm. My favorite is this picture of someone looking for – and presumably finding – a bit of respite in one of the congested utility-filled back alleys of Wan Chai:

Maybe the character of the public realm in Hong Kong is simply a result of people not having as much individual or personal space as we do in the west, or maybe there’s a deeper cultural meaning associated with valuing the collective over the individual. Whatever the reason, it sure makes for a wonderful urban experience…….one that leaves me feeling that the streets of Seattle are pretty boring by comparison. The energy of Columbia City’s central core, Broadway in Capitol Hill, Market Street in Ballard, and parts of the Seattle Center (sometimes) are pockets of pedestrian-dominated exceptions that come to mind, but my impression is that many of our streets are simply paths rather than places. I don’t think this is a question of design. I think it’s a question of use. And societal values.

Maybe the character of the public realm in Hong Kong is simply a result of people not having as much individual or personal space as we do in the west, or maybe there’s a deeper cultural meaning associated with valuing the collective over the individual. Whatever the reason, it sure makes for a wonderful urban experience…….one that leaves me feeling that the streets of Seattle are pretty boring by comparison. The energy of Columbia City’s central core, Broadway in Capitol Hill, Market Street in Ballard, and parts of the Seattle Center (sometimes) are pockets of pedestrian-dominated exceptions that come to mind, but my impression is that many of our streets are simply paths rather than places. I don’t think this is a question of design. I think it’s a question of use. And societal values.

What I am left wondering is:Â Why is so much of our built environment geared towards getting somewhere rather than being somewhere?

>>>

Scott Wolf is a Partner at The Miller Hull Partnership and an Affiliate Fellow of the Runstad Center for Real Estate Studies in the College of Built Environments at the University of Washington. The interdisciplinary group of Fellows recently returned from a research trip to Hong Kong. Read more about their findings on their blog. (Photos by the author.)

C200: Success : Damage Ratio

Peter Drucker famously said: “You make what you measureâ€. He’s right: effective metrics focus on the outcomes that a group or society values. But still, sometimes things go awry. Unintended consequences can result from diligently pursuing a too-limited set of metrics.

Last month we visited Hong Kong with a small group of Seattle built environment professionals and graduate students from the University of Washington. Hong Kong’s admirable efforts to house everyone, to create transit access for everyone and to preserve nature have led to the most sustainable pattern of land use we’ve ever seen. The way the city has planned and developed is the envy of policymakers trying to contain sprawl in nearly every North American city.

But the constant densification has significant downsides: large new development podiums at rail stations swallow up the public space that was once small pedestrian alleys. The podiums are less permeable, have little or no real public space within them and what public space there is can’t be customized by individuals. Furthermore, in a place where living compactly depends on tight community ties, tearing down old buildings and displacing inhabitants has tremendously disruptive effects on both business and residential communities.

The takeaway? It’s important to define what you want…and just as important to define what you don’t want.

The takeaway? It’s important to define what you want…and just as important to define what you don’t want.

The reciprocal is true in our backyard: the Washington State SEPA review process focuses on only the negative impacts of a project, and often ignores positive impacts, leading to erroneous conclusions about the need for change. We need an environmental review process that reminds us of what we’re getting from rezoning SLU or South Downtown or Beacon Hill.

In any ratio, there are only two ways to achieve a greater result: 1) increase the numerator, or 2) decrease the denominator. Choosing to measure only part of the equation yields incomplete (at best) or truly misleading (at worst) results. We need to remember both as we look at public policy tools and metrics: what do we want and what we have to give up to get there.

>>>

A-P Hurd and Scott Wolf are Affiliate Fellows of the Runstad Center for Real Estate Studies in the College of Built Environments at the University of Washington. The interdisciplinary group of Fellows recently returned from a research trip to Hong Kong. Read more about their findings on their blog.

C200: The Place of Seattle

Most great cities in our world have an engrained sense of place created by the choice of the site for the city. Often cities were sited on bodies of water affording access which in turn “naturally†creates a sense of place from the beginning. Fortunately, more often than not, city designers overtime have celebrated this sense of place by the organization and development of the urban environment.

Seattle has three qualities which stand out in defining its distinctive sense of place, its geographic position, natural setting and its climate. Historically Seattle is located in the northwest corner of the United States, though more recently Alaska claims that distinction. As such Seattle has always been considered removed, a ways away, but its position in a corner contributes to its sense of place. The City is located on two bodies of water, Puget Sound and Lake Washington and within eye sight of two mountain ranges, the Olympics on the west and the Cascades on the east. Mount Rainier stands out as a landmark to the south of Seattle. These natural environments, a visible part of everyday life, impact ones sense of life as well as sense of place.

Seattle, like many cities built on the shores of large bodies of water such as Chicago, San Francisco, Tokyo and Vancouver are also distinguished by being on an edge. Part of ones’ experience of the sense of place is the contrast between a usually vibrant urban environment on one side and the openness to the water on the other.

The climate of Seattle is also distinctive, especially in the context of the larger United States. It rains or drizzles more often than most other cities though in actuality has fewer inches of rainfall per year than cities such as New York or Philadelphia.  But Seattle is known for its grayness however when it is clear it is bright and clear, unlike Philadelphia, Chicago or New York in July. The grayness attributed to Seattle impacts the attitudes regarding the use of color in architecture, There are those who feel that the use of color should be of a subtle nature essentially complementing  the grey light. This is also a tendency in the Scandinavian countries which are a part of the historical culture of Seattle. However there are others who feel it is necessary to introduce brightness and contrast into the environment to off set the grayness, though others would argue that bright colors are more appropriate in climates of brightness in essence a celebration of that type of “southern†climate.

The temperatures are relatively mild, with very little snow in the City (Though a significant amount in neighboring mountains) and summers rarely reach temperatures above 80 degrees and there is no sense of the humidity felt in many east coast cities. Another  quality of the weather is the distinctive, beautiful cloud formations that are a regular, ever changing element of this sense of place.

The position of Seattle at a latitude of 46 degrees also contributes a distinctive quality. In the winter it becomes dark early in the evening and light late in the morning. Most commuting to and from work is done in the dark from November through February, but in the spring and through the summer the opposite is true with light remaining as late as 10 PM. The rain and grey skies contributes to the darkness in the winter and the bright, clear skies in the spring and summer adds to the lightness. This uniqueness contributes to the way of life in Seattle and is a quality again contributing to the sense of place of Seattle.

>>>

Lee Copeland FAIA is a Consulting Principal with Mithun.

C200: Coming Home

Rediscovering cities means coming home. Because over the past few generations, the predominant culture of the United States became drunk on a way of life that negates the city. And we got lost out there.

Since cities first appeared 5000 years ago, no culture in history has so widely strayed from the settlement patterns that sustain the health and spirit of human beings. Our bodies were designed for walking; our brains were designed to learn directly from others; our souls were designed for cooperation and sharing; our hearts were designed to be close to other hearts, and deeply attached to place.

A million plus years of evolution in closely knit social groups doesn’t take kindly to isolation. And isolate is what this country’s most pervasive built environment does. No coincidence either, that our prevailing economic philosophy is one that worships the individual.

But we’re waking up. Human nature is rebelling. A life of strip malls and subdivisions viewed through the windshield doesn’t cut it. People want to live in places that cultivate connectedness—to the physical city itself as well as the people in it. As happens when you walk instead of drive.

And it’s not about size, but form. True cities, small and large alike, have the power to bring people together. To bring them home.

>>>

It’s been 29 days, 67 posts, and 14,000 unique site visits since yours truly started this Citytank C200 series thing. The response was much greater than I ever anticipated, and I thank all of you who contributed. All the pieces that have been submitted to date have now been published, and so I thought it fitting to put a punctuation mark on the end of this first wave of the series with my C200 contribution, above. I plan to continue publishing new C200 pieces as they are submitted, and I encourage people to go for it. Meanwhile, Citytank will start featuring more of the sort of content that made hugeasscity a household word.

C200: The City In History

As we have seen, the city has undergone many changes during the last five thousand years; and further changes are doubtless in store. But the innovations that beckon urgently are not in the extension and perfection of physical equipment: still less in multiplying automatic electronic devices for dispersing into formless sub-urban dust the remaining organs or culture. Just the contrary: significant improvements will come only through applying art and thought to the city’s central human concerns, with a fresh dedication to the cosmic and ecological processes that enfold all being. We must restore the city to the maternal, life-nurturing functions, the autonomous activities, the symbolic associations that have long been neglected or suppressed. For the city should be an organ of love; and the best economy of cities is the care and culture of men.

…

The final mission of the city is to further man’s conscious participation in the cosmic and historic process. Through its own complex and enduring structure, the city vastly augments man’s ability to interpret these processes and take an active and formative part in them, so that every phase of the drama it stages shall have, to the highest degree possible, the illumination of consciousness, the stamp of purpose, and the color of love. That magnification of all the dimesnsions of life, through emotional communion, rational communication, techonological mastery, and above all, dramatic representation, has been the supreme office of the city in history. And it remains the chief reason for the city’s continued existence.

>>>

Lewis Mumford pretty much invented the concept of the multidisciplinary interpretation of cities when he published The Culture of Cities in 1938. Twenty three years and 12 books later he published the classic The City in History, the last and third-to-last paragraphs of which are reprinted above (emphasis added). It says a lot about Mumford that he concludes his masterwork—widely recognized as one of the most influential books on cities ever written—by twice invoking the word “love.”

C200: Transit as a Market Extender

< The context of the Mt Baker light rail station is Southeast Seattle, where the transit investment has not been enough to stimulate significant redevelopment - yet; photo: Dan Bertolet - click to enlarge >

There is a lot of discussion on the effect of transit on property values and redevelopment in cities around the country. Usually the boosters claim that transit helps and opponents claim that it does nothing. The truth? As with many other questions the answer is “it dependsâ€.

As we’ve seen over the last decade the demand for living downtown has been increasing as more and more people see this as a viable option and more developers build to the existing demand. But where does this demand come from? And can it be replicated in any part of a region?

The reason for this ability to build more density actually comes from increasing market demand from people who want to live in these areas, and are willing/able to pay the prices necessary to support constructions costs associated with higher density. To build up, developers have to be able to hit a specific price point that justifies their costs and provides an acceptable return on the investment. While all of the future plans TOD hope for density projects, the truth is that without increasing market values, some subsidies that help the developer furnish the required parking or other amenities, may be required, the further you get from an area with higher market values. The same is true for suburban development—in order to make it pencil, subsidies such as roads and utility extensions need to be a part of the deal.

So, like suburban development needing road and freeway access, urban development becomes more valuable with transit access. Markets can be extended. Some of the most successful redevelopment districts and hip neighborhoods are those which are proximate to downtown and were able to use the power of downtown to increase the viability of their redevelopment potential. We’ve seen this in places like the South End in Charlotte or the Pearl District in Portland. Both of these areas have transit connections that have pulled the downtown, which has the major market, a little closer. Ultimately this is where streetcar and light rail corridors are helpful.

Typically, 15 minutes is the time transit can travel before the market extension starts dropping away. Further down the line, development is possible and still warranted, however it won’t be supporting denser steel frame buildings. But why does this matter? If we want to think of creating walkable communities, transit needs to be focused on connecting major destinations. The major destinations are generally employment centers with less opposition to development and the ability to grow up instead of out. This means development closer to downtowns is better, and, for that matter more transit supportive. Suburban oriented transit doesn’t do as much work carrying people or pushing buildings up.

So with that being said, let’s rethink how we’re developing transit today. While we’ve invested further in roads and other subsidies for sprawl, its time that the pendulum swung back and provided opportunities to build up assets around our regional economic engines, creating a critical mass for the next generation and their economic future. Let’s use transit to extend markets where we can.

< Mount Baker Light Rail Station in Souteast Seattle; photo: Eagle Eye Aerial Photography via Sound Transit - click to enlarge >

>>>

Jeff Wood is New Media Director and Chief Cartographer at Reconnecting America in Oakland, CA. Dena Belzer is president of Strategic Economics in Berkeley, CA.

C200: Urban Fabric: The Form of Cities

< Roosevelt Row in Phoenix, AZ: a half block of fine grain lost in a sea of course grain; photo: Mario Grey - click to enlarge >

Urban fabric is the physical form of towns and cities. Like textiles, urban fabric comes in many different types and weaves.

Coarse grain urban fabric is like burlap: rough, large-scale weaves that are functional, but not usually comfortable. Such places consist of large blocks, predominated by vehicle dependent retail and corporate centers; or multi-block mega projects dropped on a city without integrating the surrounding city or community. Not only do coarse grain fabrics NOT provide many opportunities for interconnecting; the fabric itself is usually inhospitable to interaction. In this regard coarse grain acts as a barrier for all but those who are there for a specific purpose.

On the other hand, there is fine-grained urban fabric. Like high count Egyptian cotton, fine grain urban fabric can feel luxurious and wants to make people linger in or around it. It consists of several small blocks in close proximity. Within each block are several buildings, most with narrow frontages, frequent store fronts, and minimal setbacks from the street. This offers many opportunities for discovery and exploration. There are virtually no vacant lots or surface parking. Also, as there are more intersections, traffic is slower and safer.

Fine grained urban fabric is not imposed on a community like its coarse cousin. Rather, it evolves over time, responding to what came before, and adapting to what came afterwards. This evolutionary process creates places that are dynamic and reflective of a neighborhood’s changing needs, able to seamlessly evolve over time from lightly developed residential areas to mixed-used retail to dense urban core. In this way, they are far more resilient than mega-projects that, when they lose a single tenant, often fail.

Yuri Artibise is an urbanist and blogger from Phoenix AZ.

C200: When Does A Suburb Become A City?

When does a suburb become a city? Because that’s what the next half century is all about.

We spent the last half of the 20th-century creating suburbs – the stuff we city types dismiss as sprawl. But, sorry, it’s not dismissable. People love it. Always have, and still do.

Whenever a society gets rich enough, people buy space. Hence the suburban instinct that flowered for the middle classes in the age of the streetcar – the technology that expanded cities exponentially in the 1890s.

Vancouver, founded in 1886, one of the first places to adopt electric-streetcar technology, and so shaped itself around the villages that formed wherever the streetcar lines went. And though we may look so mid-20th-century modern with all our concrete high-rises, we are still function more like a late-19th century city. And also because we didn’t build freeways into our core.

Unfortunately our surburbs did build freeways, wide roads and parking lots – lots of ’em and not a lot of transit - making themselves almost totally dependent on the auto and truck for almost everything. Today, those suburbs are vulnerable. Having driven out all other transportation choices except driving, they are now hostage to the price and availability of oil.

So what to do? What distinguishes the central area of Vancouver, given the imits of water and mountains, was to build on the streetcar fabric and make high-density development sufficiently attractive that all classes of people could imagine living in it. Vancouver provided enough practical transportation choices – walking, cycling, transit, taxis – sufficient to accommodate more people without accommodating more cars.

The rest of the region has decided that it too would like a bit of what Vancouver has. In the regional town centres from North Vancouver to Langley City, they’re embracing density, transit and the public realm. High-rises sprout all along the rapid-transit lines. In our largest municipality, Surrey, they prohibit the use of the word ‘suburban.’ They’re using public investment - a new library, a new city hall, walkable public spaces, more transit – to stimulate private-sector development, to concentrate into true ‘downtowns.’

The suburban ideal may remain dominant in the older subdvisions, but they too like the idea of choice – in accommodation, workplaces and transportation. And they’ll need to, if the suburb is to have a future.

But then they’ll call it a city.

>>>

>>>

C200: Affordability Is Critical To Great Cities!

< The Low-Income Housing Institute's Bart Harvey apartments for low-income seniors in Seattle's South Lake Union neighborhood; photo: Dan Bertolet - click to enlarge >

Great cities are places where people can live, work, go to school, spend time with family and friends, and have access to what they need and want.

Notice I said that great cities are places where people can live AND work. The fact is that many people who work in Seattle live somewhere else. (The same is true in many major US metropolitan areas.)

Why do people live so far away from their jobs? For some, it’s a choice based on the lifestyle they want. But for many people, it’s not much of a choice – we have to live where we can afford the rent. And without enough affordable apartments and homes in the city, where most of the jobs are located, many working people spend hours (and lots of money) commuting from far away.

Living far from a job often means spending less money on rent, but more on transportation. For working people in the Seattle, the total cost of housing and transportation averages more than 60% of household income! That doesn’t leave much for other necessities, much less discretionary items.

The money is a big concern for people who live from paycheck to paycheck working at jobs that we all rely on (health care support, child care, retail, janitorial, hospitality, and so on) – and so is the time that working people should be able to spend with their families.

The economy, the environment, and community stability all benefit when people have affordable choices of places to live close to their jobs, to services they need, to their schools and communities – and the city thrives. We need more housing choices that are affordable for everyone!

>>>

Sarah Lewontin is the Executive Director of Housing Resources Group, a Seattle-based nonprofit provider of excellent affordable apartments that enable low-wage working people, their families, and low-income seniors to live independently throughout their lives. She serves on the Boards of ULI-Seattle (where she co-chairs the Housing Affordability Task Force), and the Housing Development Consortium of King County, and is an active member of Leadership for Great Neighborhoods.

C200: In The New “Rentership Society,†Cities Offer The Best Means To Share Scarce Resources

Theoretical physicists have recently garnered attention for asserting that cities universally become more economical as they increase in size, as contrasted with living organisms, for which physical mass and efficiency are inversely proportional. While in the abstract this assertion begs the question as to the city size at which the relationship might break down (Two Tokyos? Ten Tokyos?), on a more basic level it underscores the assumption that cities, if properly organized, can provide an efficient template for the provision and sharing of goods and services. Moving from global abstraction to local context, this thesis is rather intuitive when applied to the planning and land use decisions facing most American metropolitan areas, including the Seattle region.

For metropolitan areas like Seattle, where low-density suburban development is the dominant land use, greater urbanization creates an opportunity to better utilize increasingly scarce economic, environmental and economic resources. The past decades of suburban expansion have created some incredible inefficiencies in land utilization, housing, infrastructure and transportation that were generally deemed acceptable in an era of rapid economic and population growth.

Today, in an era of increasing economic and resource scarcity, the financial tradeoff of low-density suburban development is no longer acceptable to a majority of the population—particularly to the next massive wave of consumers, the Millennial generation born to the Baby boomers. This generation will almost certainly be the first in our nation’s history to be less well-off than their parents, as defined by personal wealth, if economic projections are correct. The costs of supporting a massive generation of retirees, bearing the burdens of enormous levels of public and private debt accumulated over the past decades, and increasingly expensive sources of energy are economic headwinds that will not abate anytime soon.

In addition, in an increasingly networked world with access to nearly every conceivable type of information at one’s fingertips, Millenials tend to prefer access to experiences over ownership of physical goods. While ownership as concept is by no means going extinct, a more urbanized future offers Millennials the ability to offset the diminution in individual financial wealth with an ability to more easily access a wider range of goods, services and experiences than did their parents a generation before.

While there is great debate as to the ideal level of density, mix of land uses, and degree of connectivity between uses that are needed to support a more efficient alternative to the suburban development, the attractiveness of a city can in large part by judged by the ability of its citizens to effectively access and share resources, including those classically defined as community facilities (open space, recreational facilities, transportation) as well as “third places†to relax, socialize and exercise that are typically not publicly owned. The inter-relationship between forced frugality and increasing emphasis on an experientially-driven economy provide a great opportunity for cities to flourish if given the necessary political support required to provide successful urban models as alternatives to the dominant suburban ones.

>>>

Chris Fiori is an urban planner and real estate development analyst with Heartland LLC.

C200: A Successful Region Needs Successful Cities

The future of our region depends on the success of our many different cities.

Passion for this place energizes lively debate about the best ways to grow – but often obscures important common ground. Focusing growth in all types of cities has the overwhelming embrace of our region’s people and elected leadership.

VISION 2040 spells out details. Built on an environmental framework, the focus for most future jobs — and homes for most of the 1.3 million more people expected by 2040 — is cities.

It’s about people being attracted to lively and diverse urban places, and more transportation choices – including 100% more transit. We can preserve rural areas, sustain our waterways, our atmosphere — and make cities even better places to live.  Tax dollars go further.

Two new efforts help:

Growing Transit Communities provides resources to support neighborhood planning. Plans grow more sustainable communities around about 100 new transit centers over the next 20 years.

A Metropolitan Business Plan to capture new low carbon jobs through something called BETI. The Brookings Institution is helping us – and making this region a template to emulate.

Let’s grow our cities with more action, built on the strength of regional common ground and lift.

>>>

Bob Drewel is the Executive Director of the Puget Sound Regional Council, which does regional transportation, land use and economic development planning with King, Pierce, Snohomish and Kitsap counties and the 82 cities and towns within them.

C200: How to Steal a Car

< Georgetown, Washington D.C; photo: paulaloe via Flickr >

The secret was to put the key in the accessory position so that the steering column turned freely. Then the little blue Honda was free to slip stealthily under the silent limbs of the pin oaks, a shadow moving into the night. And Mom never never did wake to shadows.

When you were half-a-block down the street, it was safe to crank the ignition. Turn on the lights, make note of the gas gauge. You’re on your way.

Drive the the six lane boulevards bounded by stripmalls to collect your friends, steer the volume higher on the stereo and turn toward the city.

1am: Georgetown is always first. Since Smash is closed, you wander around among the student housing, hoping for an invitation into an open door. More often than not, you just climb the Exorcist steps before turning onto Key Highway, swallowed by the city.

2am: The clubs are closing. Youthful yells and sloppy sex spill out on the street. Congressional aides hike their discoball skirts, and duck between dumpsters to relieve their bladders. At the time you couldn’t figure out why they didn’t go in the club; now, having been in a few, you know; the street was safer and cleaner. Smart girls; doubtless Democrats.

3am: The night is winding down; the voyeurs are heading home, taking it slow. Cops would ruin the night. Your arm, dangling out the window, is cooled by the exhaling Canal Road canopy. The double yellow line extends beyond the headlights and into the night.

4am: Why did you never learn? You always ruined the night with Denny’s. Refill the engine, not too much. Drive past your house, a bit up the hill. Line it up. Kill the headlights and put it in neutral. Let your eyes adjust, let out the brake, and drift on home.

>>>

Brice Maryman no longer steals cars. Honest. He is now gainfully employed as a landscape architect in Seattle and is the past board chair of Great City.

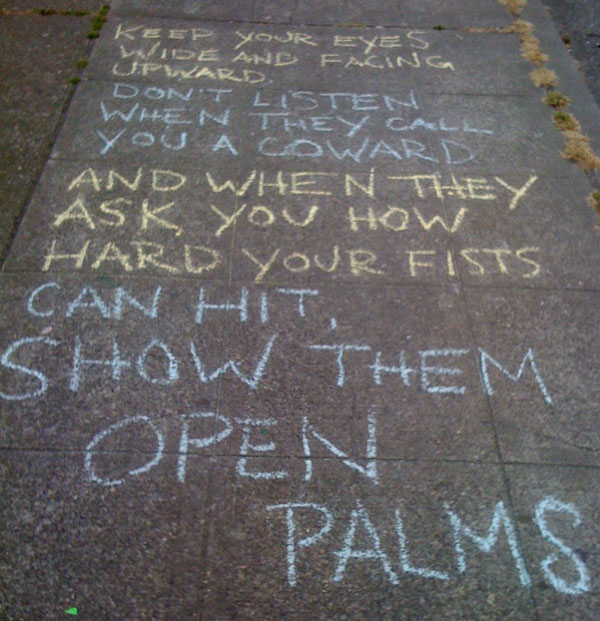

C200: The Best Is Yet To Come, Seattle

< Seattle sidewalk; photo: Mike Kent >

In The Secret Lives of Buildings, architect Edward Hollis wrote: “Architecture is all too often imagined as if buildings do not—and should not—change. But change they do, and have always done. Buildings are gifts, and because they are, we must pass them on.â€

I would extend this sentiment to cities and, specifically, to Seattle. Ours is a city whose gifts are clear to even the most casual passer-through: an admirable balance of natural beauty and urban density, a thriving arts scene, and a meaningfully engaged citizenry, to name a few.

I will highlight one more exciting aspect of our city: its obvious potential to become even better. Seattle has the unique opportunity to make the leap from “great†to “world-classâ€, and I am excited to contribute my small part toward its evolution.

Rather than lamenting the relative meagerness of Seattle’s transit systems compared to, say, Portland’s, let’s celebrate our nascent light rail and streetcar as the kickstart of what could become a magnificent transportation network. Let’s learn from our transit forebears how to improve own transit network, perhaps itself one day a model for excellence. For now, though, let’s recognize our transit network for what it is: a work in progress.

Let’s seize the opportunity presented by Seattle’s future transit hubs and underbuilt core neighborhoods like Denny Triangle and South Downtown by working together to encourage higher-density development that enables future Seattleites, as Mayor McGinn might say, to “walk, bike, and ride†in their daily commutes.

Let’s honor our city’s rich architectural and cultural history by preserving vestiges of Seattle’s past and weaving them into its future as a foundation for sustainable growth.

Seattle is not yet a finished product—it’s not even close. It will not be the same place 20 years from now, or even five years from now. It will be even better.

So, breathe, Seattle. Smile! We are an incredible city, and our best has yet to come.

>>>

Mike Kent is an urban planner and Director of Kent Planning Solutions, based in Capitol Hill.

C200: The Business Of Tackling Climate Change

It is tough to think about global warming today. As I was drafting this, the earth was shaking, coastal villages in Japan were washed to the sea and the earth was knocked off its axis by 6.5 inches. But, think we must, and then pull all our energy in the direction of a low carbon future. A growing alignment of smart businesses, environmentalists and the military know that our common interests are truly entwined. And we will need to tap every last ounce of the power of both business and NGOs if we hope to have a chance of saving ourselves.

In our daily life, we all support businesses of some sort. Businesses are an essential thread of societal fabric. Businesses can thrive and contribute to the right side of climate change—many do. The literature is replete with businesses investing in energy conservation, smart commuter strategies for their employees and authentic “green†behavior. This saves resources, retains employees and attracts green-minded customers. We can help businesses by making programs less opaque, more accessible, easier to access—and, as reliably discerning customers.

The times are troubling, but the sun will rise tomorrow. And if the enviros and the business community work together we’ve still got a good shot at transforming our cities quickly and effectively enough to make a difference.

>>>

Charlie Cunniff works on the Seattle Climate Partnership and as the environmental specialist on the Business Advocacy team at the City Office of Economic Development.

C200: Acknowledgements

< The author, second from right, performing with the George Metesky Ensemble at Max's Kansas City, 1983: photo by Stephen Blos >

I grew up in a small town in northeast Ohio. It was an idyllic childhood, really, not unlike the one depicted in Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons. A Colonial house on a tree-lined street. A walk or bike ride to school. Sailing small boats, paddling canoes. Roaming the woods with good friends. However, something started to happen when I moved to the big city for architecture school. There was a lot of friction against my established view, shoulder-rubbing, boundary-stretching, and mind-expanding, bumping up against extraordinarily smart and passionate people who became friends, collaborators, mentors and sometimes clients. I’ll mention a few: In Toronto Peter Prangnell, Daniel Libeskind, Alberto Perez-Gomez, Tom O’Brien, and Philip Beesley. In New York City Isamu Noguchi, Alfredo De Vido, Christian Marclay, Sussan Deyhim, Glenn Branca, and Vincas Meilus. In Seattle Dan Bertolet, Joe Zajonc, David Rousseau, Norma Davidson, Kathryn True, Patty Borman, Chuck Pettis, Alan Durning, and Alex Steffen. Intensely values-based (rather than form-based) design. Phenomenological architecture. Noise, bricolage, and free improvisation. Ecological design, dowsing, carbon-neutrality and sustainable urbanism. Would any of this have crossed my path had I stayed in a small town? Unlikely. It took cities to do that. Coming face-to-face with these people and ideas changed my life for the better. For these cities therefore, I am truly indebted. Toronto, New York, Seattle, thank you.

>>>

Rob Harrison AIA, architect and Passivhaus consultant, played guitar in a punk-jazz band with Dan Bertolet before he was fashionable. He and his car-free family park their bicycles in a green-roof garage he designed. He aspires to do only multi-family Passivhaus projects in the city, but will be pleased to design your Passivhaus cabin in the woods in the meantime, while the world catches up.

C200: Community Re-defined

Cities are a unique fabric of interwoven networks. They present opportunities for relationships that might not otherwise exist and take the concept of community to a whole new level, enveloping the social, economic and cultural fabric of place. The richness within the social and cultural aspects of each of these unique networks works closely together providing a more meaningful experience for the community and people within it. From a structural standpoint, cities are dense populations that share resources. From a humanistic approach cities bring together a wide array of people to solve complex problems. And, most importantly, cities provide a meaningful purpose and existence for its inhabitants.

Urban cities have one major advantage over suburban communities… efficiency. Cities allow for efficiency of space, materials, and time. They are environmentally sustainable because they minimize impact by creating density instead of sprawl. But their sustainable nature doesn’t end with environmental impacts—cities are sustainable communities.

Cities become the breeding ground for innovation. Within a city you will find individuals working to cure cancer, build the next aeronautical advancement, and improve the pertinent social services that provide health, education and opportunity to all individuals. Cities bring together millions of individuals that want to better their own community as well as the larger social issues that may be affecting communities around the globe. On the lighter side, cities provide quick, efficient and meaningful gestures of space and opportunity for people to gather together to enjoy the finest food, entertainment, culture, education and services.

True sustainability isn’t about using the greenest products. It is about living all aspects of your life in a sustainable manner. True sustainability is about sustainable relationships, sustainable businesses and sustainable environments. Cities bring all of these aspects together to work in a cohesive manner.

>>>

Mark R. Schuster is founder of The Schuster Group, a Seattle-based real estate investment and development firm, and author of Lofty Pursuits: Repairing the World One Building at a Time.

C200: I Dream The City Resilient

Green buildings are great. Now we need to connect them together into smart, green, and semi-autonomous districts to create a resilient city.

We know it can work here. The recent Yesler Terrace Sustainable District Study shows that a green building/sustainable district/centralized infrastructure hybrid can provide high reliability and high sustainability for the same or lower costs than traditional infrastructure. For example, by treating and reusing wastewater on site we can reduce Yesler Terrace’s future potable water use by up to 50 percent and wastewater flows by up to 70 percent for less cost than paying Seattle’s sewer and water rates. The study also shows that a district thermal loop fueled by renewables could provide the hot water, space heating and cooling needs of Yesler Terrace redevelopment. The energy for the loop could be cost-effectively provided by sewer heat recovery, solar hot water, and geo-exchange. Where appropriate the energy district could even be extended to willing neighbors.

Adding such district systems to Seattle is the next rational step on the path to a resilient and sustainable city. Smart, self-organizing systems with real-time monitoring and feedback loops will play a role. But it is not just technology alone. Sun and shade, rain and wind, soils and vegetation are also foundational no-tech solutions that contribute to resilient and beautiful district infrastructure.

< The Hammerby Sjostad brownfield redevelopment in Stockholm employs numerous sustainable district strategies. >

Districts designed for resilience recover more quickly from extreme events – whether earthquakes, tsunamis, storm surges, rainstorms, snow, or heat waves. If parts of the centralized systems go down, the resilient districts can supply much of their own needs. If district systems have difficulties, the green buildings or centralized systems can serve as temporary backups. All of them working together create a robust and flexible buffer that helps to deflect the impacts of rare but predictable disturbances.

A resilient Seattle of green buildings, semi-autonomous districts, and centralized backbone infrastructure would be adaptable and sustain itself over time. It would elegantly connect low-tech/no-tech natural systems with high-tech water, energy, mobility, and communication systems. At each scale, citizens would see natural systems working together with sophisticated technologies to create highly livable and aesthetically beautiful surroundings. As a design strategy it would future-proof Seattle by improving the likelihood that the system and its services will perform successfully under a wide range of future environments and day-to-day conditions. And as the Yesler Terrace study shows, district systems can thrive in direct competition with the costs and risks of business-as-usual.

>>>

Steve Moddemeyer is a Principal for Sustainable Development at CollinsWoerman in Seattle and co-authored the Yesler Terrace Sustainable District Study.

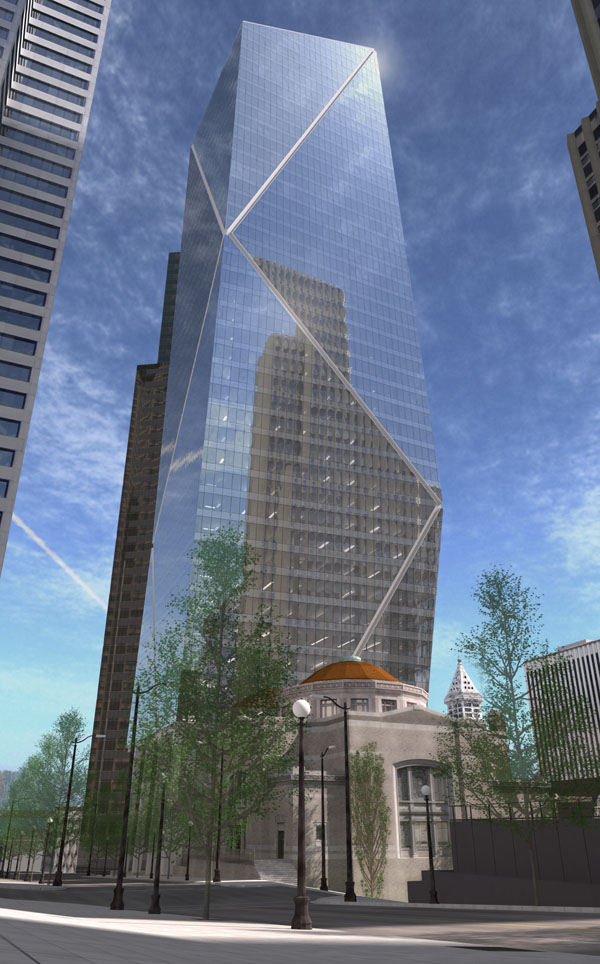

C200: How Preservation Ethos Plays Into A Great City

< As part of a 2007 development deal for the tower rendered above, downtown Seattle's First United Methodist Church - completed in 1910 -was saved from demolition. >

I often have to dispel the common assumption that preservation is about saving old buildings. That’s partly correct, but falls well short of what the movement actually represents. I’m sure the notion of saving buildings that resides in many of the public resulted from either reading about efforts to save a particular building, or their own involvement in a struggle to save a school, church, favorite building or whatever.

Preservation traces its modern roots to the saving of Mount Vernon. But today the issue for preservationists is less about saving a particular building or even a whole neighborhood district. It’s about “placeâ€. Place does matter.

So what is place? It’s the combination of factors that make any collection of buildings special whether it’s your own neighborhood, or the Pike Place Market. Yes there are buildings that help create that “place†but it goes much deeper. Place happens in neighborhoods and communities whether there is a historic building or not. But for preservationists the built environment is the glue that holds it together.

The preservation movement has understood for some time it’s not just about saving a historic building as a stand-alone effort. It’s about making sure that the special qualities that define an area are preserved along with the important examples of architecture so future generations can enjoy the place.

After all, sustainability starts with preservation.

>>>

Kevin Daniels is President of Daniels Development, and serves on the Board of Trustees for the National Trust for Historic Preservation in Washington, D.C.

C200: This Is What A City Makes Possible

C200: Density and Community

< On E Pike St between 11th and 12th Ave on Capitol Hill, two new mixed-use residential buildings that replaced parking lots integrate well with the existing urban fabric; photo: Dan Bertolet - click to enlarge >

Choices about reducing carbon are shaped by public policies. Carbon emissions are lower in communities that are compact and that provide access via transit and non-motorized travel among jobs, homes, and commercial and recreational activities. Density by itself, however, only works with community.

Seattle has already taken great strides in developing communities that are compact and sustainable over time. We are also in a great position to move further in this direction, but it will take careful and thoughtful public policy to ensure that we hit the sweet spot that matches denser communities with high quality of life.

Like most American cities, Seattle lost population between 1960, when it had 557,000 people, and 1990, when it had only 516,000. Most of Seattle is zoned for single family residences, and, except for downtown, most of the rest was dominated by low rise apartment and commercial buildings. Seattle never suffered wholesale abandonment of neighborhoods – population loss mainly reflected smaller household sizes, with most dwellings still occupied. With a downtown that never totally lost steam, and a network of thriving neighborhoods with modest commercial hubs at their centers, Seattle was well-positioned for success when the City’s leaders embraced the principles of Washington’s Growth Management Act and a more urban community.

Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan, adopted in 1994, projected adding 72,000 households over the next 20 years, and called for a major reinvestment in downtown neighborhoods, allowing greater height and encouraging more residential development. And it called for developing the centers of most other neighborhoods into ‘urban villages’ with several stories of housing-over-storefront buildings.

Change alarms many people, and this was no exception. Many residents felt their single-family neighborhoods were at risk, and embraced a nostalgic vision that rejected the new plan. Resistance peaked in 1994-1996, when neighborhood meetings drew hundreds to attack City leadership and opposition leader Charlie Chong won a special election for an open Council seat vacated by one of the advocates of the Comprehensive Plan.

Fortunately, there were many who were attracted by this vision, and Mayor Rice’s administration came up with an ultimately successful way to attain it. The Mayor and Council approved giving 37 designated centers for population growth the opportunity to develop neighborhood plans. Communities got guidelines for participation, a toolbox of ideas, and money to hire their own planners. They were asked to decide whether they could meet their assigned growth targets, what land use changes they would need to do so, and what other actions would ensure continued neighborhood livability.

The response was extraordinary. While there were a few rough spots and conflicts, given the opportunity to calmly look at how new density would impact their communities, 20,000 people participated and every one of the neighborhoods accepted the growth targets and zoning changes needed to accommodate them. This was an extraordinary victory for growth management — and for the Seattle process when run properly.

Neighborhoods also came up with an agenda for the City: some 7000 recommendations for investments, policy changes, and actions. For the last ten years, the City has worked to fulfill these expectations, and has successfully accomplished the majority, focusing on the highest priorities.

The lesson is that density can work, that people will accept it, and that thoughtful engagement and responsive government make the difference.

Seattle now has 55,000 residents living downtown. Most neighborhoods have reached their growth targets, and some have exceeded them. There has been no resurgence of NIMBYism – in fact, communities continue to embrace change, especially those that are now receiving or will soon receive light rail service.

As Seattle thinks about its next moves towards building communities that are not auto-dependent, adding the next increment to our population, a lot will ride on how neighborhoods are engaged in the discussion. Some additional land use changes will be needed – but most of them will increase density on property already zoned for mixed use of multi-family. As neighborhoods found out in the earlier round, there is neither need nor reason to focus on single family areas – density works better in areas that already have some development.

Additional heights? In some cases. Generally, once you get over a few stories, additional heights don’t add much to the vitality of the street environment or community, and there are limited areas where tall buildings really work. But in most urban villages, 6 to 8 story buildings work from a street and community perspective, and add significant housing and support for neighborhood small businesses. Some cities that are models of dense urban development – like Paris and Copenhagen – have managed density and transit very well with heights limited to 6 to 8 stories.

The bottom line: there is a remarkable amount of density that can be accomplished while making communities better places to live and without arousing significant neighborhood concerns. These neighborhoods will need parks, libraries, and other community facilities. And they will need jobs and businesses, and developers that are willing to make investments, and transportation networks that provide workable alternatives.

>>>

Richard Conlin has been elected four times to the Seattle City Council, and currently serves as President. He was one of the founders of Sustainable Seattle, and a participant in the neighborhood plan process – before being elected and Chairing the Committee that oversaw the approval process.

C200: The Kids Are Alright

< Thurgood Marshall Elementary in Seattle's Central Distric; photo: Dan Bertolet - click to enlarge >

In the last two decades, plenty of cities—including Seattle—did what was once considered impossible. They drew legions of well-educated, middle class residents back to the urban core with high-tech jobs, a thriving arts and culture scene, and dramatically lower crime rates. What they didn’t get: children.

Among major cities, Seattle has the second lowest proportion of households with children (next to San Francisco). Seattle may be an extreme case, but cities across the country tend to have fewer school age children than the suburbs.

So what does it matter if modern cities are havens for childless couples, empty-nesters, and single condo-dwellers?

If you care about density, plenty. Two-thirds of Seattle is zoned single-family residential—a proportion that isn’t changing anytime soon. Backyard cottages and transit-oriented development can increase density, but think of the difference keeping families with young children in the city would make (without, I should mention, prompting a NIMBY freak-out).

Seattle Public Schools has taken steps that make it easier for families to choose staying in the city over decamping for the suburbs. First, the district ditched its complicated, confusing assignment plan in favor of a system that guarantees students a space in their neighborhood school. Now, if you know your address, you can predict where your child will go to elementary, middle, and high school.

Second, the district is publishing detailed, annual reports about the performance of each school and providing tailored resources to those that are struggling. The reports show that many schools have a long way to go (especially those south of I-90), but an analysis by UW’s Center on Reinventing Public Education also shows that some schools are beating the odds. Take Concord Elementary in South Park. It has roughly the same proportion of low-income students as neighboring schools, but Concord students not only outperform their peers in absolute terms, they are improving faster, as well.

These changes mean that families who are priced out of north end neighborhoods like Wallingford and Ballard—traditionally known for their good schools—have reliable information about strong schools in more affordable parts of the city (February’s median home listing price in South Park: $175,000).

And when families with children choose to stay in Seattle, it reduces growth pressure in the suburbs and creates a denser, more livable city.

>>>

Nathan James lives and works in Seattle.

C200: Leadership for Great Neighborhoods

< Seattle's Roosevelt neighborhood; photo: Dan Bertolet >

We all know that cities are the way to go. The better the city, the better off we, and the planet, are.

Founded three years ago, Leadership for Great Neighborhoods (LGN) is a coalition of community and neighborhood leaders, residents, business owners and other stakeholders that shares the Citytank philosophy that cities are the answer. But while Citytank’s vital role is to educate, inspire, to contradict orthodoxy and to shake things up, the mission of LGN is to engage at the neighborhood and city-wide level, with the goal of making Seattle more livable, more exciting, more fun.

The question is how will LGN do it?

To paraphrase Mary Elizabeth Lease, we are going to write fewer white papers and raise more hell.

What does this mean? We engage at the neighborhood level on planning, land use and zoning issues to make sure neighborhoods have the proper tools to shape their community. We also work with city leaders to make sure proper funding tools are available to pay for the things that make neighborhoods livable and attractive to people from all walks of life. We hold city leaders accountable in our quest to help Seattle achieve it’s full potential.

We look forward to Citytank and LGN working as a complementary pair: Citytank provides the insight, the ammunition, the information, and the creativity to help advocates bring about the changes we need to make Seattle work better for its people. LGN deploys the foot soldiers working in communities and at City Hall to make Seattle live up to its ideals.

>>>

Jessie Clawson and Dan McGrady are conspiring to get the City of Seattle in gear through Leadership for Great Neighborhoods.

C200: There Is No One Solution

< Two Union Square, downtown Seattle; photo: Dan Bertolet >

Cities, like their creators, are a wonderful mess. And as with people, the mess of interdependent complexity that makes up a city can be either a blessing or a curse, depending on how it is directed and cultivated.

The city’s myriad, interrelated systems require balanced care, or the whole organism withers. For example, in most cities across the United States, the intimately connected systems of land use and transportation have, in a vicious cycle, become malignantly dysfunctional. This imbalance stresses other systems—social, economic, and ecological—eventually dragging down the entire city.

Restoring balance will never happen if we stubbornly resist change. But nor will it be accomplished by obsessing on singular, narrow ideas such as the eradication of cars or density as a cure-all. Achieving a healthy balance in a city takes a holistic approach that recognizes complexity. And that recognition starts with an understanding of the complete spectrum of viewpoints.

One of the goals of Citytank, and the C200 series in particular, is to give exposure to a wide spectrum of ideas for the city. This is not to say that all ideas are equally valid, or that we should avoid criticizing those ideas with which we disagree. But we need to get it all out on the table.

If you’ve got a viewpoint that has been neglected in the Citytank C200 discussion so far, please email your idea to tanked@citytank.org.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban designer and the founder of Citytank.

C200: The True Meaning Of Cities Revealed

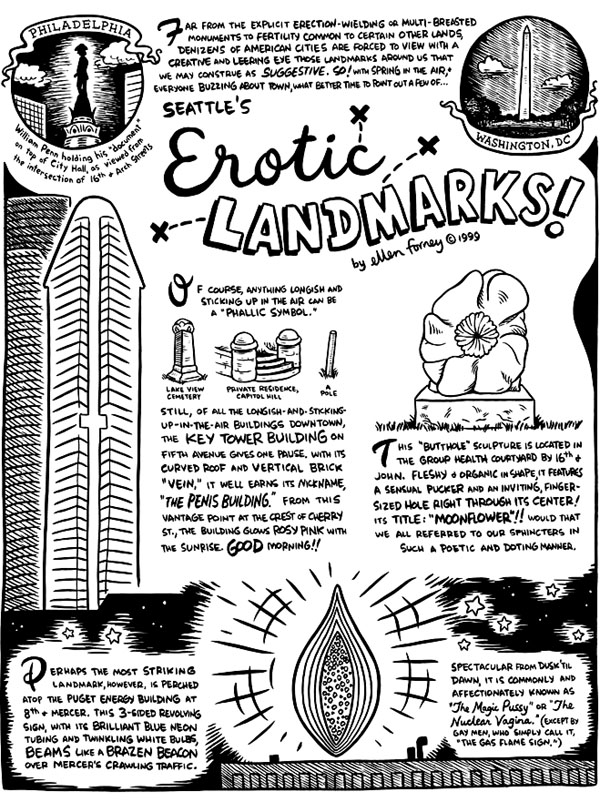

>>>

Seattle cartoonist Ellen Forney is currently working on a graphic novel for Penguin/Gotham Books.

C200: Spatial Diversity

The variations in the fabric of the street are among the things that make a city great. Looking down the street, block after block of possibly wonderful buildings, our eye is caught by the green splash of a pocket park or entry court. The punctuation of a dramatic entry or canopy also draws attention. Beyond physical form, the corner grocer elicits a different kind of street life than the rest of the block. So too does the athletic club, the barber and the café.

Looking up from our sidewalk bench, a different kind of diversity is possible. Perhaps a second floor terrace extends from a meeting room. Behind a ribbon of glass, a set of professional offices may exist, different from the apartments above marked by a rhythm of punched window openings and balconies.

The vast and uninhabited plaza in the center of the business district also represents a diverse city fabric (in a negative way) as does the night club: vacant by day and vibrant by night, the soup kitchen dispensing a little warmth and nutrition to street denizens, the civic building with one grand entry along a hundred yard stretch.

All of these examples, good and bad, represent diversity in the human scaled fabric of the city. In a 500 year old city both horizontal and vertical diversity abound. Humans have molded the built environment to fit their needs and potentials. Within a block in most older cities, one can rest in a pocket of greenery, play chess in a coffee shop window, buy groceries, be entertained, live, work and play. This condition is tied to diversity in the built world.

In our fast paced world, cities rise and fall at a fast pace. Vacant blocks become large developments housing hundreds of families. Others become office towers or shopping meccas. All of these conditions arise in the context of our automobile culture and the seven year proformas. City builders ask themselves: what market is strong now? How do we pull profit out fast? Decisions are made based on the most dependable and broadest based data. If apartment vacancies are low, then we build apartments. But, if retail is foundering or office space is abundant, that big block apartment development will avoid both – these kinds of diverse uses won’t even appear on the proforma unless required by codes. And then, they will be listed as a net zero in the profit line or even a loss. Yet, a variety of uses and the related diversity of built environment are key to the charm and success of older cities.

One difference, of course, is time. The old city has had a chance to learn, to adjust and to change. Economic fluctuation is reflected in those surprises that we find around the corner and the broad range of uses that we find. Generations within families and neighborhoods have evolved the uses they need within their local environment. Another difference is the car. We can drive to do our big box shopping, diminishing the base line need for local markets.

Perhaps these conditions are temporary. Fifty years ago there were no big box stores. Will they exist in another fifty years? We cannot know, but we can speculate that the age of the car is in a state of flux and may decline. Even if it doesn’t, perhaps the young culture of the United States can teach itself the benefits of diversity. Maybe we can develop zoning that promotes the pocket park or the corner grocer within the context of our development realities and the large projects that seem to dominate our built environments. Could it be that the “local†movement will manifest itself in the marketplace and that a building that accommodates work, exercise, entertainment, retail sales and of course housing can thrive? Signs are pointing in this direction. I hope that the next period of growth will explore the richness that diversity can bring and help us to create great cities in the 21st century.

>>>

Ray Johnston is a founding partner at Johnston Architects pllc, a Board Member of Futurewise, and Chairman of the TwispWorks.

C200: Old Pipe Dreams

I wrote this piece during an academic conference where ‘resilience’ is the theme. It’s mostly theoretical and I want to be doing things. Specifically, arranging our built environments to be more efficient. For example, efficiently collecting sunlight (I live in a very sunny place).

Not only is much of our modern built environment poorly arranged for solar access, but many building envelopes are not ready for wide-scale solar deployment either. Our trees – so necessary for shade to keep inefficient buildings cool – are often directly in the path of the sun; yet removing trees for solar power exposes poorly-insulated walls and roofs.

Our design standards should be developed to ensure roofs are oriented toward the sun, and that trees do not block the ‘solar window’. Our building walls and roofs should be built or retrofit to insulate to higher standards. In colder areas, many older cities ‘tilted’ their street grid 23.5° to the northeast to receive winter sun and melt snow and ice. Our green infrastructure can help gray infrastructure, not hinder it, by shading pavement, raising quality of life, and collecting stormwater.

We have been doing these things for centuries. For a short time, we forgot how to do them. Look around. Find the patterns. Let’s make them again.

>>>

Ex-Seattleite Dan Staley now lives on Colorado’s Front Range where he specializes in green infrastructure.

C200: Design Is A Verb

< The New York Center for Architecture >

Design decisions impact every aspect of our urban lives. Do we feel safe on the street? Good design. Can we live close to parks, shopping, childcare? Good design. Do our homes and offices offer clean air and sunlight? Can all of us access vital resources, regardless of income? Are our buses and trains, parking lots and libraries intuitive to understand and easy to access for people of all abilities? Are our parklands and waterways healthy, and is there adequate habitat for our wildlife? Are we inspired and uplifted by what we see and feel and smell around us? Great cities depend on great design.

It’s in our best interest to live in a city where all of us feel empowered to realize the promise of great design. Though it is ubiquitous and powerful, however, design is largely invisible, reflecting decisions made behind closed doors long before their physical impacts are evident. How do we put the power of good design in the hands of everyone, educating and engaging all of us to be informed stewards of our designed environment?

Cities across the world are answering this need with design centers, built to educate and invite public participation. From the San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) to the New York Center for Architecture, from Copenhagen to Shanghai, design centers are thriving as intermediaries between design and the public, empowering citizens to take an active and knowledgeable role in everything from policy to development, parks to transportation.

Seattle needs a design center, too. A living laboratory that translates complex issues to help the public become more effective participants. In keeping with our Seattle character, a center could enable thoughtful decision-making through access to tools and information. Programs, exhibits, research, charrettes, town hall meetings and publications are the arsenal of a design center geared to promote civic engagement in shaping community. Seattle has a long history of citizen action on the built environment; a center would offer a common living room, a staging ground for empowerment. To learn more about design centers and efforts underway to create one in Seattle, visit http://aiaseattle.org/urbandesigncenter.

Design is a verb, and we need to do it together.

>>>

Lisa Richmond is Executive Director of the American Institute of Architects Seattle, working to improve the quality of our environment and society through design.