Deciding Between Cars And People On 23rd Ave

The City of Seattle is currently weighing the options for an upgrade to 23rd Ave in the Central Area, the outcome of which will say everything about whether or not the City walks its own talk about creating places for people instead of cars. There is no room for compromise, literally. Due to space constraints, the only way that 23rd Ave can become a street that isn’t a hostile place for people and a dividing gash across the neighborhood is through removal of travel lanes. And to do so means car capacity will be sacrificed.

The choice is clear: people or cars? What’s it going to be, Seattle?

As shown in the video above shot at 23rd and Marion, much of 23rd Ave has four travel lanes squeezed into a 60-foot right-of-way that only leaves room for narrow sidewalks and no buffer between pedestrians and cars. It’s a scary, dangerous, and wretched place to walk. To parents of small children, a road like this is a constant source of anxiety, and for good reason.

I live half a block off 23rd Ave and for 15 years have experienced first hand how it severely degrades quality of life and compromises the City’s goals to create walkable neighborhoods. As I wrote in 2008:

Because walking along 23rd is a such a totally miserable experience, very few people do it, street life is dead, and 23rd is like a black hole cutting across the neighborhood. Pedestrian-oriented businesses fail. And street environments that repel pedestrians have a tendency to become havens for street crime — it is no coincidence that 23rd and Union, as well as 23rd and Cherry and other areas further south on 23rd Ave have had troubled histories.

23rd Ave is one of the City’s most important north-south arterials. But if the City decides that all four travel lanes must be preserved to maintain vehicular capacity, there is pretty much nothing significant that can be done to make 23rd Ave a more people-friendly street—there simply isn’t space.

The only way that 23rd Ave can be tamed is through the removal of travel lanes to open up space for wider sidewalks, bike lanes, or other buffers between moving cars and people on the sidewalk. Such a reconfiguration would also be expected to reduce speeding, which is rampant under current conditions.* But there is no question that removing travel lanes will also reduce capacity and increase traffic backups during peak periods. Complicating the issue further, a lane reduction could also increase travel times for Metro’s #48 bus line.

We can all acknowledge that this will be a difficult decision. Some folks will be outraged over the potential for worse traffic on 23rd Ave. But though it may be difficult, to me the right choice is obvious. Because creating neighborhoods where life without a car is an attractive option is one of the most important strategies for ensuring Seattle will be a city that can thrive through the coming decades of increasing resource constraints and climate change. We need places that are less about enabling cars to tear through on the way to somewhere else, and more about supporting human beings with feet on the ground.

These goals are widely agreed upon in the typical rhetoric of Seattle’s electeds, and are also supported by numerous adopted City policies. What happens on 23rd Ave will be the pudding.

>>>

*After I petitioned the City for a crosswalk on 23rd at Marion St about ten years ago the City clocked cars passing through the area and found frequent speeding.

Having recently returned from a trip to Taiwan, including a number of days spent exploring Taipei, I came away with a few personal insights related to urban issues currently being discussed in Seattle. I acknowledge that Taipei and Seattle are quite different. Taipei is a big Asian metropolis that fully embraces its high-density neon-hued 24-hour urbanity. It is the capital of Taiwan and has almost 7 million people in the metro area. The Seattle metro area has half of Taipei’s population and remains, in my estimation, a reluctant big city where emerging urban and longstanding provincial cultural values collide. We embrace certain features of city living (arts, professional sports, a vibrant high-end culinary scene) but simultaneously still seem to fear population density, revere retro-agrarian hobbies like backyard chicken raising and hold sacrosanct inexpensive (or free) on-street parking. Taipei is unabashedly urban. Seattle is moving in that direction, but slowly.

All cities draw on their historic, cultural and political patterns to find their own unique form and organization, which evolve over time, but for millennia urban planners, politicians and developers have drawn lessons from other places to inform and ultimately improve their own cities. As Seattle continues its evolution as a city, here are a few lessons I think we could learn from Taipei.

1. Density requires open space. An inevitable consequence of Seattle’s continued economic and population growth is increasing population density – more people living in multi-family residential (condo, townhouse or apartment) buildings in close walkable proximity to transit and amenities. A key feature of dense but highly livable urban living is open space, where city dwellers can get out and play. Taipei does this very well, with one prominent and relevant example being the vast assemblage of park, bike and walking paths and wetlands that stretches for miles along the Danshuei and Sindian rivers in central Taipei. On a weekend day, the paths are packed with cyclists, walkers, bird watchers, Tai Chi practitioners, families at playgrounds and many sports teams. In many ways it feels much less like a tourist attraction than like the city’s back yard, where citizens come to recreate, relax and enjoy a respite from the crowded city. With the redevelopment of Seattle’s waterfront, we have a generational opportunity to create a similar amenity for our city – not just a place primarily for tourists like our current waterfront, but a place for Seattleites to recreate and consider their own.

2. Don’t be afraid of signage. A city’s primary function, indeed what makes the city humankind’s greatest invention, is to bring people together to exchange ideas, goods and services. Commerce is at the very heart of urbanity. Building signage is nothing more than the city’s various merchants visually announcing what they have on offer. It adds vibrancy, color and life to the streets and in some cases is like a table of contents for buildings – telling you what is inside and inviting you in to explore. Some of Seattle’s best-loved icons are bright signs – the Pink Elephant and the P.I. Globe come to mind – so we have a tradition of embracing signage. Why not let our buildings better express their contents and embrace the fact that our city is a thriving commercial hub with businesses we are proud of?

3. Embrace street food. Far from detracting from the success of sit-down restaurants, Taipei’s street food provides a tantalizingly interesting and appealing feature to the sidewalk (adding new and appealing sensory dimensions of smell and taste) and creates an almost block party like feel as people evaluate, discuss and stand in line for various snacks. These street food carts serve to invite people to be a part of the interesting street life, where they are naturally inclined to shop and eat at other establishments. Further, this sort of homegrown micro-enterprise entails far less cost and risk than opening a bricks and mortar restaurant, meaning street food carts can also allow small entrepreneurs to get a start. Take, for instance, the food cart pod on First and Pike, which has transformed a surface parking lot into an active and interesting sidewalk. Why not encourage more of this?

4. Unconventional retail configurations can not only survive, but succeed in unexpected and appealing ways. One of Taipei’s most striking features is the unexpected variety of retail shops – both their content and configuration. Unlike Seattle, where retail is traditionally found on the ground floor in spaces of at least a few hundred square feet (and often much larger) located on arterial streets, Taipei has many small and narrow retail shops (in some cases just six or eight feet wide and ten to twelve feet deep), narrow shopping alleys with no car traffic, and restaurants and retail on the second and third floors (and in some cases much higher than that). To a large extent, this diverse and finely detailed retail pattern is a reflection of population density. Clearly, Seattle’s current population cannot support the same quantity or diversity of retail as a city like Taipei. But, in many ways, by not fitting into a formulaic retail pattern, these spaces are more interesting, intriguing and inviting. An example here in Seattle is Post Alley or the warren of shops in the Market. Most retail consultants would describe locations with these characteristics are sure failures, yet they work because the adjacent activity, scale and interest draw people in. And, as with street food, small retail footprints and one-off locations allow small businesses to set up shop, with lower gross rent, increasing employment and the retail mix in the city.

One of the most delightful things about travel is that it opens one’s eyes to new realities and possibilities. Though Taipei and Seattle have a great deal that differentiates them and many features of the culture and built environment simply do not translate, there is much we in Seattle could learn and apply to our own city.

>>>

Gabriel Grant is Vice President at HAL Real Estate Investments and is currently an Affiliate Fellow of the UW’s Runstad Center for Real Estate. All photos by the author (click on some of them to enlarge).

What are the Ingredients for Designing a Family-Friendly Downtown?

Having grown up in the suburbs, and as my husband and I consider starting a family of our own, my interest in this topic continues to grow. It seems to peak when I travel to other cities and countries where there is a stronger presence of children downtown than the average American city. For example, seeing Italian mothers toting their children to daycare through the heart of Milan on bicycles made me reflect on my childhood mode of transportation to school. My school bus ride or trip in the family car courtesy of my parents certainly didn’t include a bike ride past a cathedral. Additionally, seeing young Japanese elementary school children, crisply dressed in their school uniforms, independently navigating the Tokyo subway system on their way to school made me think of the first time I independently rode public transportation . . . in college. And seeing high school students run their track workouts through Grant Park in downtown Chicago made me consider the land use ramifications of the typical one-story suburban school and surrounding playfields and single-family homes.

Today, however, certain North American cities are seeing a growing number of parents choose to stay downtown after they have children rather than immediately flee to the suburbs. Thanks to the Seattle Chapter of the American Institute of Architects and their Emerging Professionals Travel Scholarship, I was able to dive head first into my passion and travel to a handful of these cities to see what, if anything, was the secret to creating a family-friendly downtown. I dug into issues of neighborhood design, urban housing, recreation, and transportation. I also looked carefully at the incredibly important link between education and housing for parents, as Jon Scholes recently described on this blog.

After my bags were put away and I had time to synthesize the neighborhoods I visited and interviews I conducted, I noticed a series of trends that are happening nationwide. One such trend is that these new urban parents are organizing to change cities, hoping that they can stay in the downtown neighborhood they love while still supporting the needs of their growing family. They are using their collective power to fundraise for playgrounds and to make their voices heard at school board meetings and city council meetings. I also came away from my travels with a number of suggested policy and design solutions to help make cities, including Seattle, more family-friendly. Those research findings are compiled in a Family-Friendly Urbanism exhibit, currently on display at AIA Seattle’s gallery space through the end of April. (1911 First Avenue, open Tuesday through Friday from 9 am to 5 pm).

Additionally, and most importantly for the future of Seattle’s family-friendliness, AIA Seattle, the Seattle Department of Planning and Development, the Seattle Planning Commission and the Downtown Seattle Association are co-hosting a day-long forum about the topic. Ingredients for Designing a Family-Friendly Downtown will take place at City Hall on April 11th. International, national, and local speakers will be in attendance to discuss housing, education, recreation, transportation, and the market realities of retaining families with children in urban neighborhoods.

Will you join us on April 11th to further the conversation?

>>>

Sarah Snider Komppa is an architectural and urban designer and former Seattle Planning Commissioner. She recently finished a year-long research project about family-friendly cities thanks to AIA Seattle’s Travel Scholarship and the support of her employer, LMN Architects.

All photos by the author (click to enlarge).

There’s sharing in our future:

The very thing that makes cities so powerful – their ability to agglomerate – will only be enhanced by the sharing economy. Academics tell us that great things grow out of dense human interaction. Picture what’s possible when those same people are further connected to each other through networks modeled in the digital age and built on the real-world sharing of cars, spare bedrooms and whisks.

I’m already hooked on Car2Go. It has probably nudged up my carbon footprint, but I have no doubt that new carsharing systems like Car2Go will lead to an overall reduction of humanity’s overall environmental impact. Parking guru Donald Shoup is fond of pointing out that the average car is only operating (i.e. not parked) about five percent of the time. Double that to just 10 percent through carsharing, and we might only need half the number of cars.

The building in the photo above houses flex space, including a new shared art workshop called ALTSpace. Coworking spaces are popping up all over the city. Okay, so the bike in the photo isn’t shared, but it soon could be.

And have you heard about Yerdle? Founded by a former Walmart executive and a former Sierra Club president, the goal of Yerdle is to enable peer-to-peer sharing of stuff that could reduce the consumption of new stuff by an estimated $200 billion per year.

More sharing means more bang for the buck, and less stuff means less greenhouse gas emissions—two things that are going to matter more and more in our resource-constrained future.

>>>

Photo by the author. This post is part of a series.

Urban Nexus: Density And The Single Family Craftsman

NOTE: The following post contributed by Great City is part of a series from advocacy groups supporting the proposed rezone in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood.

>>>

Two decades ago Seattle set off on a path to preserve neighborhood mojo, attract jobs, and ensure neighborhoods had a robust supply of urban housing. Neighborhood planning efforts in the 1990’s were predicated on the assumption that to preserve Seattle’s single family neighborhoods, we were going to have to maximize development in our Urban Village neighborhoods and Urban Center neighborhoods to accommodate future population and job growth. After decades of striving towards perfection in transportation planning, we also added that funding transit infrastructure needed to be a core element of neighborhoods designed to absorb the most density.

Creating dense urban housing that attracts families—in the same way a Wallingford Craftsman attracts families—will require a rich mix of affordability, design, and amenities. And I am certainly not the first to point out the logic that more housing inventory makes cities more affordable by offering supply to meet demand. A broader city-wide conversation about the types of housing we want to incentivize to meet our city’s needs over the next 30 years is overdue. But that conversation shouldn’t be shoe-horned in at the eleventh hour, as some Councilmembers are now attempting to do with the South Lake Union rezone. Rather, it should happen with thoughtfulness, technical specialists, and a clearly articulated vision for what we seek to achieve. Housing is a critical component of a carbon efficient, affordable, and livable Seattle, and addressing the challenge is going to take our best thinking, innovation, and leadership.

As our Seattle City Council considers the long awaited South Lake Union rezone, I encourage neighborhood planning advocates to get involved. Density in South Lake Union and other urban centers means preservation of a single family home lifestyle in other parts of our City. It means less sprawl, less regional traffic, and more equity for our infrastructure investments. Now is the time to move the South Lake Union rezone forward and finally enable the kind of development that will bring all these benefits. Lackluster, underdeveloped “bread loaf” projects will fill the void in the short term if we once again make perfection the enemy of good.

>>>

Great City Board Member Jessie Israel recently participated in Eric Becker’s film short on Placemaking & Seattle. Watch, read and get involved in the conversation: http://vimeo.com/53098694

Photo of South Lake Union from Eastlake Ave by Dan Bertolet – click to enlarge.

The People and The Food: A Policy Fairy Tale

Once upon a time, there was a state that faced an obesity epidemic. In particular, many economically disadvantaged people who lived there were struggling with their weight and as a result they suffered disproportionately from Type 2 diabetes and heart disease. At the same time, the population of the state was growing, and prices for healthy foods – such as fruits and vegetables – were increasing, making them less affordable to poor people.

The State decided to start a subsidized healthy lunch program in schools to make sure that economically disadvantaged children were developing healthy eating habits. At the same time, they granted more land to fruit and vegetable farmers to help them grow more food and meet demand.

When the legislators met to decide this, one of them asked: “But won’t the farmers make more profit if we grant them more land?”

“Yes, potentially,” replied another. “We had better tax the fruit and vegetable production from that new land to make sure that the farmers don’t make too much money.”

“I know,” chimed in a third, “let’s use the money we get from taxing fruit and vegetable production to pay for the healthy lunch program!”

As you might imagine, the farmers were somewhat surprised by this policy decision but for a while they went along with it.

Some years later, the healthy school lunch program was struggling to meet growing demand from a steadily increasing population. The legislators went back to the farmers to announce that they were tripling the level of the tax on additional farmland grants. “But wait,” said the farmers, “if you keep raising the taxes on this additional land, you are working directly against fruits and vegetables being affordable. In the limit, you may make it unprofitable for us to farm this land, and that is not good for our state’s fruit and vegetable supplies.”

So the legislators hired a consultant (who was on the board of the school lunch program) to ask them how much money the program needed, and how much the farmers should provide in extra taxes. The consultant had the very difficult assignment of telling the legislators how much profit farmers should be allowed to make.

One farmer came to see the legislators and said: “Don’t you see, taxing us is not making healthy foods any more affordable to the population as a whole. Growing affordable fruits and vegetables needs to be part of your health policy. You can’t do it all by just giving more money to the school lunch program!”

Another farmer suggested that health is really a systemic challenge. It depends on widespread access to affordable healthy food, a great school lunch program, access to preventive care, and land use planning that makes walkable neighborhoods and healthy lifestyles possible. “We need all these things,” she said. “You need to look at these things all together, and not get less of one, and more of another.”

One of the legislators was not convinced: “Let’s set up a task force of people from the lunch program, and ask them what they need, and how they see the problem.”

“No,” replied the farmers. “The point is, you need to set up a task force that looks at all of these things together, and challenge your task force to come up with a plan and policy that optimizes around health outcomes, not around only the metric of how many students are served by the lunch program.”

Here are some other thoughts the farmers had:

- The task force should have lots of different kinds of people on it: macro-economists, health policy experts, preventive care specialists, grocers, land use planners, farmers, and people from the school lunch program.

- One of the questions the task force should consider is asking farmers what it would take for them to grow more food on the land they have: are there any regulatory barriers that prevent them from maximizing their yield?

- To the extent that revenue streams are needed to fund the recommendations of the task force, it should look at multiple sources of revenue in addition to taxes on fruit and vegetable production. These might include taxes on soda-pop as well as other sugary and fatty foods, or taxes on people who keep their land fallow and unproductive for many years thereby restricting land supply for growing food.

The legislators thought this over. Now this systemic kind of change was not very sexy stuff. It was definitely harder to model and quantify. It was going to take a long time. It was going to be really hard to get front page coverage in the Seattle Times.

But it also made sense. So they did it. And their State was able to grow, and deal with the complexities of that growth without making myopic mistakes. And the State thrived, and its people ate healthier, and they were healthier.

And they all lived happily ever after.

>>>

Above image of Politics, Law, and Farming in Missouri by Thomas Hart Benson taken from the cover of Wendell Berry’s What Are People For?

In spite of its name, incentive zoning is a tax and taxes are the opposite of an incentive. We tax cigarettes partially for the revenue, but as a public health intervention it is very successful. The higher the taxes on cigarettes, the lower the smoking rate. By taxing new development we’re sending a message: building more housing is a bad thing and we’ll make it more costly if you do it.

The premise of incentive zoning is like something out of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. According to the Seattle Municipal Code, building more housing creates negative impacts, especially “an increased need for low-income housing to house the families of downtown workers having lower-paid jobs.â€

More housing is a bad thing that has to be offset by taxing that new housing to create housing at a lower price. That’s right, the Seattle Municipal Code, the DNA of the city’s development, is built on the premise that more housing actually makes things worse in the city, so bad in fact that we have to tax it to create, well, more housing.

For some of us it’s clear that this premise is utterly false. What we really need is a true incentive that would coax developers to build more units even though they and their bank might not be sure there is demand for those units. In the real world, developers try to build just enough units to ensure low vacancies and steady rent revenue, no more and no less. True incentive zoning would reduce the risk of building too many units, encouraging an outcome that has broad benefits for the City and region.

But we have it completely backwards. Developers want to build more housing, and we’re discouraging them. If they built more housing, rents would be more competitive and people who earn “workforce†wages might choose to rent in South Lake Union, give up one of their cars, and skip home ownership for a while, setting aside their savings for a home purchase later.

Seattle City Council should back away from the proposals they are now considering to increase the taxes on new development in South Lake Union and possibly throughout downtown as well. Implementing such measures now, when housing demand is rising, will end up turning more newcomers to the region away from Seattle: exactly what we don’t want.

>>>

Roger Valdez is a blogger and Seattle resident.

NOTE: The following post contributed by the Cascade Bicycle Club is part of a series from advocacy groups supporting the proposed rezone in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood.

>>>

For too long, we’ve been doing it wrong.

Thanks to powerful corporations pushing for a roads-only approach, for decades we have spent most of our money on costly new roads instead of making our existing ones safer for everybody. New roads meant new subdivisions, splattered across our region’s hinterlands.

We forced ourselves into our cars and made our cities less livable for working families and less safe for kids. Families who want to drive less don’t have any options and our neighborhood streets aren’t safe for our kids.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

For nearly a decade people in South Lake Union have been working together on a plan to make their neighborhood better. They have worked with our elected leaders on a plan to invest in making streets safer for everybody and provide everyone with the freedom to get around without a car.

The proposed South Lake Union rezone would create a neighborhood where people can easily and safely walk, bike or take transit to work, school, shops, restaurants, and places of worship.

This is our opportunity to do it right. Our City representatives should stand up for what families need and approve the proposed rezone.

Small, Affordable Apartments: Seattle Needs More, Not a Moratorium

< Rendering of proposed microhousing project at 12th Ave and East Marion St in the Central District by David Neiman Architects >

When I moved to Seattle in 1989, I was 22. My first apartment was a studio on Capitol Hill at Malden Avenue East and East Mercer Street. I lived there for six months, then moved into a series of group houses in Montlake and Green Lake. My rent in the group houses was all I could pay back then. Living alone was out of the question on my income. Sharing a room in a house of people met through Seattle Weekly or other classified ads was the way most of my friends were living as well. We were fresh out of college and working multiple jobs to get by.

Today, I live in a single-family house with my kids, and we all enjoy the privacy and space that we are fortunate to be able to have. However, I have not forgotten what it was like to be young, poor, and struggling to find safe, affordable housing.

Choices in Seattle have grown since I first moved here. In recent years, an old model of housing, congregate housing (also known as aPodments) – small, affordable private apartments with some shared living space, such as kitchens — has become popular with builders. Conventional one-bedroom apartments on Capitol Hill run $1,100 or more per month while rents in these units start at about $500-$600 per month including utilities. Property owners have realized that there is a large market of people who can’t afford to rent a conventional house or apartment. These may be students, recent graduates, people going through life transitions, or people who just don’t have the large incomes that are needed to live in conventional, market-rate Seattle housing. Many in this group are happy to live in newly constructed, safe, affordable, small apartments with some shared space.

Congregate housing is privately-developed, de facto affordable housing being built throughout Seattle without public subsidies. Recently, six congregate houses were built on a single-family street near my home in Pinehurst. The buildings are simply constructed and are not beautiful. However, they are new, safe, and affordable, and they give nearly 50 people homes along a bus line near shopping and jobs.

Unfortunately, some well-connected and persistent homeowners in Capitol Hill and Eastlake either never experienced the struggle of finding safe, affordable housing in Seattle or have forgotten what it was like. They have called on Seattle Council Member Tom Rasmussen, who is now considering emergency legislation prohibiting any new congregate housing. They demand for neighbors to have input on what any future congregate housing looks like, where it can be located, and more.

All of the measures that these neighbors are asking for, especially full design review, will only result in the increase in the cost of these units and will likely delay new units from being built. This is at a time when Seattle employers are hiring new workers and rental rates are rising and Seattle City Council is working hard to support affordable and workforce housing. A moratorium on the private development of affordable housing that is working is not what we need right now.

Having many housing options available at a range of rent levels is a simple equity issue. It allows people choices to select their best living arrangement. These small, affordable apartments are a success story. They are working at providing the housing we need. We don’t need to fix them, we need to make it easier to build them.

If you have concerns about the possible loss of affordable housing in Seattle, please reach out to the city council now and share your thoughts.

>>>

Renee Staton is a neighborhood activist who lives in North Seattle.

This post originally appeared on SLOG.

NOTE: The following post contributed by Forterra is part of a series from advocacy groups supporting the proposed rezone in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood.

>>>

Whether from an economic, transportation, housing, or ecological perspective, the central Puget Sound is interconnected. Yet we often divide our region into its component parts—from counties to neighborhoods—to achieve focused outcomes. Doing so is not without reason, but too often we overlook opportunities for achieving goals at multiple scales. The Landscape Conservation and Local Infrastructure Program is an exception; it links urban infrastructure financing with incentives for rural conservation. The City of Seattle is on the verge of showing the region how it’s done in its South Lake Union rezone.

Advocates for the rezone want a great urban place with compact development, mixed-use buildings, housing that is affordable, transportation options, public spaces, and beautiful design that complements preserved landmarks. Thanks to its form of tax increment financing, the Landscape Conservation and Local Infrastructure Program supports this vision by financing infrastructure investments. In South Lake Union it will provide $27.5 million for a community center, green streets, and/or pedestrian, bike, and transit projects.

In exchange, the neighborhood’s growth will generate rural conservation using a real estate tool called transfer of development rights. Development in South Lake Union is expected to conserve over 25,000 acres of farms and forests over the next 25 years, making a local rezone regionally transformative.

South Lake Union: Part of Our Regional Vision & Obligation to the Next Generation

NOTE: The following post contributed by Futurewise is part of a series from advocacy groups supporting the proposed rezone in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood.

>>>

We all deserve the opportunity to live and work in a great neighborhood where we have a chance to succeed.

But for much of the 20th Century, thoughtless sprawl consumed our region’s farms and forests. Middle class families were pushed to rural subdivisions, creating longer commutes, more expensive household and infrastructure costs, disconnected communities, and loss of open space.

To change the sprawling patterns of our past, two decades ago the state adopted the state Growth Management Act to encourage growth in our cities while protecting our farmland and forests.

Now is a pivotal moment for our region and the success of our state’s most effective policy in creating livable communities. Over the next 30 years, another 1.5 million people will move to our region. To rise to our climate challenge and to create more equitable communities, we must now build housing, jobs, and services near one another while also maintaining good design practices.

The South Lake Union rezone does this. Thousands of new jobs and housing – including affordable housing — get created. An estimated 25,000 acres of farms and forests get protected. Historic buildings get protected. $27.5 million gets invested in street and community infrastructure.

South Lake Union is a realization of our statewide and regional planning legacy. And now it’ll be part of our legacy to the future. Let’s get it done.

Driven into Poverty: Walkable urbanism and the suburbanization of poverty

American suburbs are a particularly bad place to be poor. Though poverty poses dire and unjust challenges no matter where it exists, sprawling and auto-dependent land use patterns can exacerbate these difficulties. And this problem is gaining urgency, as more and more of America’s low-income individuals now live in suburbs (or are being pushed there), a phenomenon the Brookings Institute has called “the suburbanization of povertyâ€.

There are many reasons suburbs make the experience of poverty worse, but first among them is that automobiles are really expensive. Purchasing, maintaining, repairing, insuring, and fueling a car can easily consume 50% or more of a limited income. For someone struggling to work themselves out of poverty, these expenses can wreck havoc on even the most diligent efforts to maintain a monthly budget. With gas now approaching or exceeding $4.00/gallon, a full day’s work at minimum wage sometimes won’t pay for a single tank of gas. The burdens of sprawl weigh heaviest on the poor.

The lower one’s income, the greater is the proportional advantage of living in a walkable, “car-optional†neighborhood. Those with limited financial resources can benefit from walkability the most. But due to the scarcity and cost of urban housing, low-income people are being driven away from walkable urbanism and into auto-dependent sub-urbanism.

In the tables below I have compiled data to illustrate this. I have used walkability ratings from Walkscore.com, and neighborhood apartment rent averages from Zillow.com. The first table shows the walkability vs. cost of Seattle’s most walkable neighborhoods. The second table shows the same info for less-walkable cities in South King County.

The Cost of Seattle’s Most Walkable Neighborhoods

|

Neighborhood |

Walkscore |

Area Median Monthly Rent |

|

Denny Triangle |

98 |

$1870.00 |

|

Belltown |

97 |

$1530.00 |

|

Cascade |

95 |

$1500.00 |

|

Ballard |

94 |

$1456.00 |

|

First Hill |

94 |

$1500.00 |

|

Downtown |

93 |

$2011.00 |

|

University District |

92 |

$1442.00 |

|

Capitol Hill |

91 |

$1370.00 |

Â

The Cost of Less-Walkable Suburban King County Cities

|

City |

Walkscore |

Area Median Monthly Rent |

|

Burien |

55 |

$959.00 |

|

Tukwila |

54 |

$900.00 |

|

Renton |

50 |

$976.00 |

|

Kent |

48 |

$920.00 |

|

SeaTac |

46 |

$862.00 |

Low-income individuals and families, those who need it most, are being prohibited from living in walkable neighborhoods in Seattle.  We are becoming what economist Ryan Avent has called a “Gated Cityâ€.

The reason housing costs are so high in Seattle is simple: lots of people want to live here and there aren’t enough available homes. As we know from basic economics, when the supply of any good is inelastic, and demand rises, so do prices. Accordingly, when housing supply is held constant, or not allowed to grow fast enough, and demand for that housing is high, rents will rise. And poor people will continue to be driven from the city.

The only way to slow this process is to build enough housing to meet the demand, preferably near transit. Incumbent property owners who seek to limit development and additional housing in their neighborhoods are therefore also supporting the de-facto eviction of the poor from the city. They are the “haves†excluding the “have-nots†once again. Though their intentions are not evil, the consequences of their actions are. And opportunistic politicians who position themselves as populist defenders of “neighborhood character†must be defeated. We must intensify our efforts to build this city. It is a just cause.

>>>

David Moser is Employment and Housing Coordinator at Neighborhood House. He is also studying public policy in the MPA program at Seattle University.

Photo of pedestrians on Pacific Highway in Seatac by Dan Bertolet.

More On Why The South Lake Union Rezone Should Be Passed Without Further Delay

NOTE:Â The following is a letter by Matt Roewe in support of the South Lake Union rezone that gets into the technical details and provides a nice followup to my letter on the same topic.

>>>

Dear Seattle City Councilmembers,

In light of the current council considerations regarding the South Lake Union rezone legislation, I’d like to share my thoughts and concerns as a professional and committed stakeholder in this process.

- The proposed legislation is the result of a thorough eight-year stakeholder and technical process: Eight years of public engagement, intensive workshops, a thorough EIS process and a well-received urban design framework all contributed to proposed legislation for the district. Many compromises have already been made since the EIS, including removing height increases in the Cascade neighborhood and panhandle area, and reducing height limits throughout the district. The council was continuously informed and briefed during the process, and several council members participated and contributed as well. While the council needs to conduct a thorough review of the proposal, I encourage you to seriously consider the results of the stakeholder process as well as the comments from the Planning and Design Commissions.

- Timing and economics: Other cities would certainly embrace the fantastic job creation,  improved tax base and vitality we are fortunate to have in South Lake Union. The re-zone is crafted to build on this vibrancy and economic success to ensure a complete, sustainable and diverse community. Also Seattle is one of the nation’s top life science and research markets that needs the support this legislation provides. Eight years of hard work have gone into this, and it should move forward while the economic momentum is strong.

- Tower bulk standards: Towers per block, height limits, floor-plate limits, setbacks, view corridors and floor area ratios have been carefully crafted by DPD to create an appropriate urban form specific to this district and less intensive than downtown zones. The stakeholders who were involved during the eight-year process, the South Lake Union Community Council, the Planning Commission and the Design Commission have all endorsed the current proposal. These standards are highly technical and appropriately balance the desire for community benefits from additional allowed development with the desire to encourage the very development that has transformed the South Lake Union neighborhood. While I encourage the council to conduct a thorough review, appropriate consideration needs to be given to the thorough process and the recommendations from the organizations who have been intimately involved in the issue and specifically asked by the council for input. Added requirements are likely to result in fewer, if any projects, proceeding and providing the desired public benefits

- Incentives vs. inclusionary housing: The proposed legislation highly rewards affordable housing as the primary beneficiary in the incentive program. As housing director Rick Hooper says, incentive zoning alone will only meet about 10 percent of the desired affordability goal. New construction cannot carry the burden alone. All neighborhoods and Seattle residents need to contribute, and more time is needed to explore and define the appropriate solution. The council should examine affordable housing incentive criteria on a level playing field across the whole city. While this is an important issue, it should not delay the approval of a single neighborhood’s eight-year process. The current legislation can also have a provision added to accommodate fee-in-lieu adjustments on a regular basis.

In general all of these issues are intertwined with each other. If the rezone criteria and incentives are made too onerous and not taken up by developers, we will simply get less housing in this district. This would be disappointing since one of the greatest concerns of the stakeholders was getting a better balance of residential and commercial development. If we believe in walkable, sustainable urban development that leverages infrastructure investment, we should not create more barriers to developing residential properties in the South Lake Union neighborhood. Alternatively, accommodating future growth in other, less central and development-ready neighborhoods, such as Laurelhurst, Seward Park and Magnolia, will certainly be more difficult and contentious.

The recent reports from Spectrum and Heartland show the lack of consensus on inclusionary and fee-in-lieu programs. Should we consider requiring a single-family home owner adding a detached accessory dwelling unit (this was a recent up-zone) to rent one bedroom out to someone with 60 to 80 percent median income? If not, then why would we ask the more urban, sustainable and responsible form of dense multi-family housing in South Lake Union to be the only one required to be inclusionary? This imbalanced approach must be addressed holistically across the city.

I understand the council wants to secure appropriate public benefit for allowing greater development capacity; however, the proposed legislation already accomplishes this goal. Requiring more will likely cause developers to not take advantage of the added height, and no housing benefits will be realized. Just going to a high-rise construction type can add $50.00 per square foot over wood frame projects. Further fees beyond those proposed or creating mandatory inclusionary housing are likely to jeopardize the financial viability of any tower project, which effectively means most developments will only build to the current “bread-loaf” base capacity. No affordable housing will be the outcome.

Already two developers with large sites have decided to only build to the current zoning and not pursue the proposed rezone option. Only two office buildings are in the advanced queue to take advantage of the re-zone. No developer yet has formally proposed a residential tower. That is a strong indication of the limited market for residential high-rise. If the council creates even less incentive, then the eight-year effort by so many stakeholders will be for naught.

Please pass the legislation as proposed. It’s well vetted and balanced.

Matt Roewe, AIA

Don’t Overburden Development In The South Lake Union Rezone

NOTE:Â The following is a letter I sent to the Seattle City Council in support of the South Lake Union rezone. This is an important real world example of the debate over taxing density, which I have previously posted on here, here, here, and here.

>>>

March 2, 2013

Seattle City Councilmembers:

I am writing to urge you to approve the South Lake Union rezone as originally proposed, without adding additional developer incentive fees or inclusionary affordable housing requirements. The fact that the rezone proposal was developed over a six year process that included extensive public engagement and neighborhood input along with exhaustive analysis and refinement would be reason enough to oppose 11th-hour changes that have not been properly vetted. But I also ask Council to consider that excessive fees or requirements on development are likely to be counterproductive to achieving the City’s equity and sustainability goals.

Over recent decades it has become increasingly recognized that dense urban areas induce enormous social, economic, and environmental benefits. This reality is reflected in a plethora of public policy at the Federal, State, regional, County, and City levels intended to promote the accommodation of population and employment growth in urban centers such as South Lake Union. It follows that intense development in the South Lake Union neighborhood will inherently deliver a wide range of public benefits both at the local and regional scales. Removing regulations that impede the beneficial outcome of development is the appropriate response, and that, of course, is why the rezone was proposed in the first place. However, incentive fees or inclusionary requirements have the exact opposite effect because they are actually a financial disincentive to the production of higher density buildings. As recent testimony to Council has demonstrated, there is wide disagreement over the cost of production and the amount of fee that would still allow developers to make what is deemed a reasonable profit. But the fact is, any incentive fee will tend to either increase the cost of producing a building, or result in less intense development to avoid the fees. Either of these outcomes runs counter to the widely agreed-upon goal of increasing density in urban centers.

Affordable housing has been a key issue in the debate, and is a salient case in point for how developer fees can be counterproductive. The biggest factor responsible for escalating housing prices in Seattle is that demand is outpacing supply. Employers like Amazon are attracting highly paid workers who want to live in Seattle and can afford to pay a lot for housing. And when housing supply is limited, wealthier people will always be able to outbid those with lower-incomes. The most effective way to mitigate this escalation is to increase housing supply, which puts downward pressure on the prices of both new and existing housing throughout the City. Incentive fees may result in the production of a relatively small amount of subsidized affordable housing, but some of the cost of that subsidy can be expected to be absorbed in the new market rate housing, driving up prices. Even worse, if developers take a pass on the incentive fees and produce less housing as a result, again, housing prices will be driven up due to lower supply. Developer fees will benefit the few who are lucky enough to get to the front of the line for a subsidized unit, but ultimately, their benefit will come at the expense of far greater numbers of people throughout the neighborhood and City who end up paying more for market rate housing.

Much has been said about the fairness of development in South Lake Union. Based on the reasons given above, I believe Council should acknowledge that one of the most effective ways to maximize fairness and equity is to ensure that regulations do not create barriers to the production housing supply, or cause an increase in the cost of producing buildings. Because in the end, restricting housing supply and increasing its cost will disproportionately punish those on the lower end of the income spectrum. (Not to mention that property taxes from new development help fund services for the less fortunate.) And every time restricted supply and the resultant high prices in urban centers causes more development to occur on the urban fringe instead, everybody loses for decades to come. Furthermore, Council should also recognize that not only is it counterproductive to overly burden new private development with the provision of public benefits such as affordable housing, it is also unfair. The burden of providing public benefits should fall on the City as a whole, including current property owners. It makes no sense at all to concentrate the burden on productive pursuits such as high density development that is a major public benefit in itself. Lastly, proponents argue that developer fees are fair because the financial hit gets passed on to a decrease in land price and therefore doesn’t impact the cost of building production. This may be true under ideal conditions, but in the real world it is exceedingly difficult to impose an incentive program that doesn’t encumber development. Given all that is to be gained from high density development in South Lake Union, it would be prudent for Council to err on the conservative side with developer fees so as to avoid the risk of compromising critical local and regional sustainable development goals.

The proposed rezone includes developer incentive fees based on thorough due diligence and City precedents. Increasing fees and requirements runs the risk of doing more harm than good. Additional encumbrances and delays on development in South Lake Union will only lead to aggravated affordability problems in Seattle, and yet more 100-year decisions that yield unsustainable development on the low-density, urban fringe. The provision of public benefits is a important issue, but it deserves a much broader policy approach that the City should address independent of the South Lake Union rezone. For the good of the City, the region, and the planet, Council should approve the South Lake Union rezone as proposed, without further amendments and without further delay.

Sincerely,

Dan Bertolet

Seattle resident

Someone’s sure going though a lot of trouble to save the lanky brick facade of the 1926 Sunset Electric building at 11th and Pine in Capitol Hill. It’s hard to imagine how the extra floor the developer is allowed to add to the new building in exchange could possibly offset the additional cost of building around all that fragile brickwork.

Either way, this project is a good example of how we tax density to fund public benefits—in this case, preservation of the Pike/Pine neighborhood’s historic character.* On the one hand, City policy dictates that adding density to urban centers like Capitol Hill is a strategy for achieving broad sustainability goals—and that is entirely correct. But on the other, the City tells developers that if they want to put more than a given level density on a site, then they’ll have to pay a toll to fund public benefits.

Apologists for this contradiction point out that if the developer did not save that facade, the reduced construction cost would not translate to lower rents, but would be pocketed as developer profit. Perhaps true, but if developers make a big profit it’s only because they have figured out how to efficiently deliver a product that a lot of people want. In any other field, that success would be admired as ingenuity and smart business.

Furthermore, the reason owners can charge prices that exceed the cost of production is because housing supply is not meeting demand, and building more supply is the only way to relieve that pressure on prices and bring the system back in balance. If there’s a potential for a healthy profit, the free market will do its thing, and eventually the so-called “problem” of developers making too much profit will correct itself as prices come in line with the cost of production. This outcome is a win-win for housing affordability and for the numerous sustainability benefits of density. In contrast, encumbering the production of housing supply—whether through density fees or other regulations, delays, or political wrangling—is a recipe for the lose-lose outcome of higher prices and less density.

As for public benefits, we need to find a way of funding them that doesn’t have the unintended consequence of penalizing new housing development, which is in effect punishing newcomers to the City to the benefit of those who are already here. A more fair approach would be to spread the burden equitably across the entire City, to both new and old properties. Indeed, the most fair approach would place a larger share of the burden on those living in low-density housing (a.k.a. single-family) that does not provide the public benefits of density.

>>>

*One could argue that this kind of “facadomy” doesn’t contribute much in the way of meaningful preservation, but that’s another debate.

>>>

Photo by the author. This post is part of a series.

Why The Green Urbanistas Got McGinn Elected

This:

Seattle Mayor Calls For Divesting City Pension Funds From Fossil Fuels

During the 2009 election Mayor McGinn won the support of urban greens including yours truly because he came across as a potential leader who would not be afraid to take bold action on sustainability issues, climate change in particular. Alas, during the first three years of his tenure McGinn has struggled with the realities of city politics, and has not been able to live up to the high expectations of many of his early backers.

However, his recent decision to pursue divestment in fossil fuels is exactly the kind of bold move that McGinn’s urbanist supporters had always envisioned. What other Mayor of a major U.S. city would have the audacity to be the first to sign on to such an out-of-the-mainstream, anti-status-quo movement? Bloomberg? Emanuel? Not. And how about mayoral hopefuls such as Tim Burgess or Ed Murray? Doubtful.

As I wrote here, 350.org’s fossil fuel divestment strategy will no doubt be derided by the “grown ups,” given that the industry is so ginormous and so embedded in our civilization. The Seattle Times, for example, has not yet covered the story (trusting in Google). And although Harvard University students voted 72 percent in favor of divestment, administration officials have said Harvard was unlikely to divest its holdings in fossil-fuel stocks.

As has happened many times over in social change movements throughout history, eventually the grown ups get with the program or die off, whichever comes first. But since in the case of cities and climate change we don’t have luxury of waiting around for that sorry process to play out, we need leaders who are willing to follow their conscience and stick their necks out even it if may be a political risk.

I find it inspiring that McGinn has taken such an important first step on fossil fuel divestment for my city. And this is just the sort of mojo that could re-energize McGinn’s base and give him a shot at another four years.

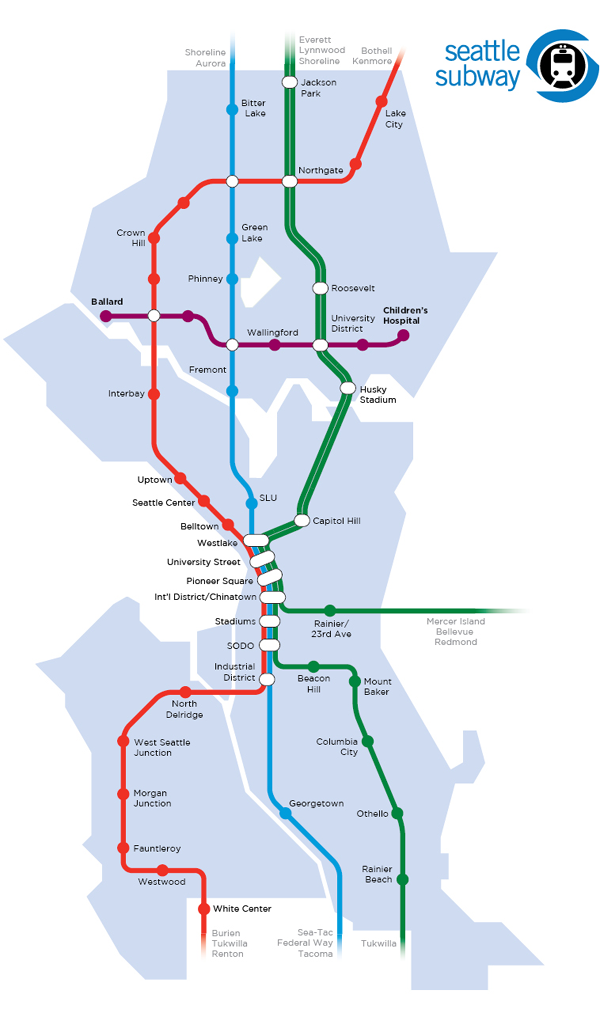

In progressive cities like Seattle, pointing out that it would be a good idea to make our urban areas more compact, walkable, and better served by transit is about as controversial as saying that we should turn out the lights when we leave the room. And it’s no secret that density is the essential enabling ingredient, the secret sauce for resource-efficient, economically competitive cities.

So why then, do we still seem to be so attached to the notion of taxing increased density? Because that is exactly what we are doing when we require developers to pay for public benefits such as affordable housing or farmland preservation if they want to build above a given height or capacity limit. Known as incentive zoning, it’s the standard formula in pretty much every U.S. city that’s experiencing growth. The trouble is, when we place a toll on the production of density, we are making the fundamental mistake of taxing the very thing we want.

Most everyone is on board with giving tax breaks to pursuits deemed vital—renewable energy, for example—in order to accelerate adoption. In the case of high density development, however, our inclination tends to be just the opposite, even though we know that densifying cities is just as critical as developing renewable energy if we hope to achieve meaningful, long-term reductions in energy use and climate-changing emissions. Can you imagine the ruckus that would ensue if a politician proposed giving tax breaks to developers if they build taller?

It’s a given among most urban planning policy wonks that if a municipality enacts a zoning change that enables higher density and therefore higher value development, then the public has a RIGHT to appropriate some of that value. Yet most of these same wonks also understand the critical role of urban density and are in favor of upzones to allow more of it. Do you notice the contradiction, reader? Attaching an extra fee to density encumbers its production, an outcome completely at odds with the well-justified reasons for upzoning in the first place. The end result is we get less of what we want, and what we do get is more expensive.

The time has come for us to get past the lingering anti-urban biases that prevent us from fully acting on the reality that the big city is not the enemy of the planet, but actually its best friend; the reality that density is a pivotal solution to a looming, time-critical planetary catastrophe that necessitates doing everything we can to create more of it quickly and efficiently.

And one significant step we can take is to stop expecting the skinny guys to go on a diet. The people who live in dense urban cores instead of sprawling suburbs are already contributing to the public good, because simply by living where they live, their environmental footprint is greatly reduced. We shouldn’t be applying density tolls that effectively tax that lifestyle choice and make it more expensive.

If we’re looking for a particular group that ought to bear a greater share of the tax burden for broadly shared public benefits like affordable housing, the rational choice would be those who live in low density—that is, put the fat guys on the diet. Because single-family homes in a city like Seattle take up so much prime land, they play a major role in jacking up housing prices across the board. Low-density land use also contributes to increased development pressure on the ex-urban fringe, simply because it uses up more land closer in. Rural preservation programs such as Transferable Development Rights ought to be imposing their fees on low-density property owners, not on dense development that inherently ameliorates the root cause of rural land consumption.

None of this is to say we don’t have an obligation to publicly fund important public benefits like affordable housing and open space. We just need to be careful that the funding choices we make do not compromise our broader sustainability goals. No, finding new sources of funds definitely will not be easy. Ultimately, mobilizing the necessary support for such restructuring is going to take a big shift in the cultural mindset that still sees city building as some sort of necessary evil, and by extension, development as an easy target for extraction.

The new mindset we need would celebrate the crazy-rapid pace of apartment development that’s now happening in Seattle’s Capitol Hill and Ballard neighborhoods as an accomplishment with as much (or more?) long-term sustainability significance as say, a new large-scale wind turbine farm. The mindset we need would recognize the unmatched sustainable development opportunity in South Lake Union—the envy of cities nationwide—and would strive to remove delays and encumbrances rather than create them (territorial views of the Space Needle, for example, would land at the bottom of the priority list).

And yes, the mindset we need would, in fact, support tax incentives for higher density development.

>>>

Dan Bertolet once wrote a blog called hugeasscity.

Photo of the 650-unit Via6 apartments—one of the highest density housing developments ever built in Seattle—by the author.

South Lake Union vs. the Space Needle

In the debate over the proposed rezone in Seattle’s South Lake Union (SLU) neighborhood, one concern that’s raised repeatedly is views, of the Space Needle in particular. Because evaluating the view impacts of buildings is a complex three-dimensional problem, misinterpretations are common, and SLU is no exception.

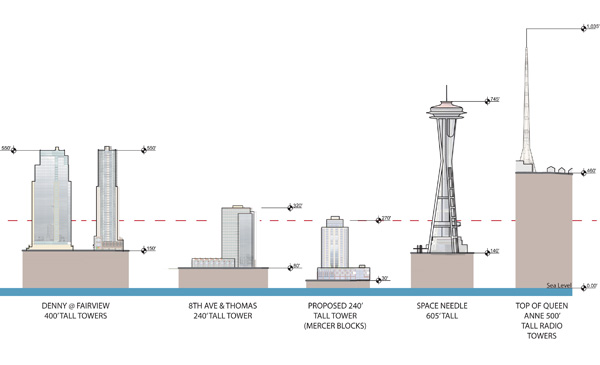

One of the key factors in SLU is topography, as illustrated in the cross-sectional drawing below (click image for enlarged pdf):

SLU is in an oblong bowl that slopes down to the lake. This topography greatly reduces the impact new buildings in SLU would have on territorial views from surrounding neighborhoods such as Queen Anne or Capitol Hill. Note in particular the 240′ towers on the Mercer blocks, and their low elevation relative to the Space Needle. Some critics argue that building height should step down toward the lake, but nature has already provided that feature.

By far the most significant view impacts of development in SLU will be to pedestrians on the streets in the neighborhood. But tower height has very little effect on these impacts, because it is the first several floors of the building that matters most to views on the street. If tower heights are held low, you can be sure that the building bases will end up bulkier to make up for it, and street-level views (and sunlight) will suffer.

It may seem counterintuitive, but if it’s views from the public realm that we care about most, then we should allow tall buildings. Vancouver, B.C. is a living example. Include rules on tower spacing and maximum floorplate—as is the case with the proposed SLU rezone—and you’re good to go.

>>>

Disclosure:Â The diagram shown above was produced by VIA Architecture under contract with South Lake Union property owners. The author is an employee of VIA Architecture.

Author and 350.org founder Bill McKibben wants to rumble with Big Oil. The reason is this:Â The business model of the world’s largest fossil fuel corporations translates to a death wish for the planet.

That’s because science tells us that the known fossil fuel reserves currently underground amount to several times as much as we can burn if we hope to keep the planet’s temperature from rising more than two degrees centigrade, the widely agreed upon redline to avoid catastrophic climate change.

Yet the corporate mission of the fossil fuel industry is to maximize profits by unearthing as much of that carbon as possible and making it available for consumption. In other words, the most powerful corporations on earth are in direct conflict with the earth itself.

How much fossil fuel is okay to burn? McKibben cites assessments that estimate a limit of 20 percent of known reserves. Corroborating, give or take, the International Energy Agency recently released the following unprecedented statement:

“No more than one-third of proven reserves of fossil fuels can be consumed prior to 2050 if the world is to achieve the 2°C goal.â€

Let that sink in. To avoid planetary climate disaster, the global community of human beings is going to have to leave untouched a vast reservoir of the energy resource that has made the modern, high standard of living possible.

It’s as if some higher being has designed the ultimate test of humanity’s wisdom.

>>>

Big Oil is so wealthy and powerful, their products so enmeshed in our everyday life, that the idea of grassroots activists “taking them on” immediately arouses my inner cynic. But the climate change crisis is so serious, and the response of our government so ineffectual, I’ve become convinced that spotlighting the sociopathic reality of the fossil fuel industry is a tactic that is long overdue.

So then the question becomes, how? Step number one, according to McKibben: divestment. As was the case with divestment from South Africa to protest apartheid, the primary targets are colleges and universities, and the movement already has its first commitment from Unity College in Maine.

Given that the massive earning capacity of fossil fuel corporations will remain even if their stock price drops, divestment is more about cultural impact than economic impact. Divestment isn’t going to put Big Oil out of business. But if and when more and more of our prestigious and influential organizations start to divest, the message will become impossible to ignore.

And the thing is, we don’t need to put the fossil fuel corporations out of business. Not if their corporate boards can face reality, take responsibility for their awesome power and wealth, and start investing their billions in profits in renewable energy sources instead of in finding ways to extract more carbon out of the ground. Is that really too much to ask, given what’s at stake?

The above photos above were taken by the author at Bill McKibben’s “Do the Math” roadshow, which had its national debut last week in a sold out Benaroya Hall.

Let The City Builders Do Their Thing

City building is messy. No great city ever arose from timidity. Like any transformative endeavor, creating a city that advances humanity requires innovation and risk.

Unfortunately, here in Seattle those truths are not widely appreciated. And the ongoing debate over rezoning South Lake Union is just the latest example of unrealistic expectations that the process of city building must be all neat and tidy, should please everyone, ruffle no feather.

City building has always caused conspicuous change. Every new building covers land, blocks views, and brings more people and activity. Residents react. Life goes on.

But now, stressed natural systems, resource depletion, and climate change have seriously upped the ante. We know that putting more jobs and people in underutilized, centrally located neighborhoods like South Lake Union is a strategy that has the potential to not only reduce our environmental footprint, but also provide significant social and economic benefits (see the South Lake Union Environmental Benefits Statement for the full story).

The proposed South Lake Union rezone is the product of over five years of public meetings, citizen engagement, planning, analysis, environmental review, and painstaking revision, and is now finally in front of City Council. But for some, that exceedingly thoughtful process is still not enough, the typical, overblown fear tactics of the naysayers well exemplified in former Seattle City Councilmember Peter Steinbrueck’s recent “REZONE-ON-STEROIDS” Facebook barrage.

Much of this sort of opposition seems to be driven by an underlying presumption that bigger buildings are necessarily a bad thing, and so allowing them is a public sacrifice that ought to avoided—or if not avoided, then compensated for by the developer. It’s stale thinking left over from our culture’s long-held anti-city bias. Because the reality of today is that high-density cities are a critical solution for a resilient, sustainable future. And it follows that a rezone enabling more development is a public benefit in itself.

Nevertheless, when it comes to the wonderfully messy business of city building, there will always be naysayers. The question at hand is, will our electeds let them sabotage one of the best opportunities for sustainable urban development in the Pacific Northwest?

>>>

Seattle City Council will hold a public hearing the South Lake Union Rezone tonight, Wednesday, November 14 at 5:30 p.m.the City Council Chambers, on the 2nd floor of City Hall at 600 4thAvenue, between Cherry and James.

Photo of messy mix of new and old near Republican and Boren in South Lake Union by the author.

Waterfront Design: Lessons from Denmark

< Inventive activators: Harbor swimming dock >

Thanks to a generous grant from the Scan|Design Foundation I’ve had the privilege of spending the last two months in Denmark. It was an excellent opportunity to examine, in detail, successful waterfront redevelopment in Copenhagen and elsewhere. The Danes have a well earned reputation for creating high quality, inviting and lively waterfronts—and even their mistakes (which aren’t many) can be informative.

Cities around the world are transforming industrial and utilitarian harborfronts into great places for people. As Seattle embarks on its own waterfront transformation this is an opportune time to explore these global solutions. Here are five lessons from Denmark:

< Public Trampoline >

Lesson One ACTIVATE ACTIVATE ACTIVATE

The best public spaces offer a range of attractions from passive to active, high brow to low. Seattleites have a long running aversion to mixing our public spaces with commercial uses, but it may be time to reconsider. In Copenhagen outdoor cafes, food kiosks and other vendors add vitality and interest–animating public spaces around the clock and throughout the year.

Lesson Two AARHUS–A CAUTIONARY TALE

Today, the Alaskan Way Viaduct is such a huge, loud and unpleasant presence it is difficult to imagine what our waterfront will be without it. All we can easily envision is that it will be better. But a generation from now few will remember the viaduct and its noxiousness, and our waterfront will have to stand on its own merit. To get a better feel for what that will be like, it is worth examining Aarhus, Denmark’s second largest city. Today central Aarhus is separated from its waterfront by a surprisingly noisy, heavily trafficked, five lane arterial.

This is a very similar condition to the proposed post-viaduct Alaskan Way, which at 66 feet wide and with an expected 30,000 vehicles a day, will be one of the widest and busiest streets in Seattle’s center city.

To avoid replacing one barrier to our waterfront with another we must design superior pedestrian connections across Alaskan Way—with elements such as wide crosswalks, long pedestrian crossing phases and high quality pedestrian amenities.

Lesson Three QUALITY OVER QUANITITY

Given the huge opportunity to transform Seattle’s central waterfront there is a natural desire to do everything at once. Some elements like the rebuilt sea wall and new Alaskan Way will obviously need to be constructed in one phase, but the Danes show that high quality materials and fine grain design gestures are the key to successful places. If resources are limited, slow implementation beats the quick and expedient.

Lesson Four BE TRUE TO PLACE

What makes places memorable–and likely to pass the test of time–are those that are unique and genuine. An excellent example is Copenhagen’s new national playhouse designed by Lundgaard & Tranberg. The structure is supported by massive upper level trusses that not only reduce the need for interior columns but also serve as a potent allegory to the earlier shipping cranes that once lined Copenhagen’s industrial harbor. Rather than facing the street, the building further responds to its maritime context by orienting its entrance, lobby (and outdoor café) to the harborfront.

< Danish National Playhouse >

Lesson Five BEWARE THE PHOTOSHOP SWINDLE

Copenhagen based Gehl Architects, an international authority on creating successful public spaces, warns against those designers whose illustrations promise public space filled with mobs of happy users when in reality the spaces end up lifeless and deserted. The most successful spaces invite you in–and entice you to stay–with a broad range of real and well thought out activities.

The removal of the Alaskan Way Viaduct gives Seattle the rare opportunity to transform our waterfront. Drawing lessons from elsewhere will guarantee our success.

>>>

Lyle Bicknell is principal urban designer at the City of Seattle’s Department of Planning and Development. He recently returned from a two month sabbatical in Denmark sponsored the Scan|Design foundation.

Â

Election 2012: Pity the Billionaire

Author Thomas Frank is perhaps best known for his trenchant analysis of how Republicans seem to vote against their own economic self-interest, in his 2004 screed What’s the Matter with Kansas.

This year Frank released another shot of brilliance, Pity the Billionaire, which explores the even more bizarre scenario wherein the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression—the cause of which is widely accepted to have been rapacious bankers run amok after years of deregulation—led not to a re-energized Left, but instead to a resurgence of the radical Right clamoring that government is the problem. In the final pages, Frank spells out what is at stake in the 2012 election:

But the scenario that should concern us most is what will happen when the new, more ideologically concentrated Right gets their hands on the rest of the machinery of government. They are the same old wrecking crew as their predecessors, naturally, but now there is a swaggering, an in your face brazenness to their sabotage. We got a taste of their vision when they reconquered the House of Representatives in 2010—in the name of a nation outraged by economic disaster, remember—and immediately cracked down on the Securities and Exchange Commission, the regulatory agency charged with preventing fraud on Wall Street. They brought the Obama administration’s one big populist innovation—the brand new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—under a sustained artillery barrage, proposing ingenious way to cripple the new body or strip away its funding. And during the debt ceiling crisis of 2011, they came close to bringing on the colossal train wreck that they have always said we deserved.

Given a chance actually to run the government of the most complex economy on earth like a small business, they will slam the brakes on spending and level the regulatory state. Dare we even guess at the consequences? At the levels of desperation the nation will hit when they withdraw federal spending from an economy already starving for demand? At the orgy of deceit into which Wall Street will immediately descend?

This, though, is for certain. As the nation clambers down through the sulfurous fumes into the pit called utopia, the thinking of the market-minded will continue to evolve. Before long they will have discovered that certain once-uncontroversial arms of the state must be amputated immediately. One fine day in the near future, it will dawn on them that the FDIC, for example, just delivers bailouts under another name; that the lazy man down the street should no more get his money back when his bank fails than when the housing market fell apart. What are interstate highways and national parks, they will ask, but wasteful subsidies for leeches who ought to be paying their way? What is disaster relief but a power grab by the losers who can’t get themselves out of the path of a hurricane?* And though public schools have been under assault for decades on charges of rampant secularism, the time is not far off when the freeloading by poor kids will be the factor that galls our leaders most.

Social Security, of course, will be one of the first institutions to go on the chopping block, as the essential injustice of protecting the weak dawns on them. Why should society pay for the retirement of someone who hasn’t been responsible and collected Krugerrands? The older generation had a rendezvous with destiny, their hero FDR used to say, and soon it will occur to America’s class war populists that every slow-moving moocher and senior-parasite needs to make a rendezvous—which is to say, that appointment with the human resources guy at the local big-box store.

Every problem that the editorialists fret about today will get worse, of course: inequality, global warming, financial bubbles. But on America will go, chasing a dream that is more vivid than life itself, on into the seething Arcadia of all against all.

*Very little suspension of disbelief required.

Density Makes Cities More Affordable

In the middle of this piece on the transfer of development rights (a useful approach, in which a developer pays farmers not to develop their farms into subdivisions, and is given a height bonus in return by local government, allowing him or her to build a taller building), there sits this strange quote:

“Of course, TDR is not without its critics. Many green-minded people will celebrate density until it arrives in the form of a high-rise condo next door. But this hesitation is about more than just NIMBYism: Anna Nissen, a design professional in Seattle who takes a critical eye to TDR, points out that upscale development — like Olive 8, for example — drives up property values and hastens gentrification. ‘The poor, the working class, and their employment have been bounced out of central cities that unaccountably are making matters worse by designating dizzying amounts of increased density,’ she writes in an email. ‘TDR rides aimlessly on top of all that.’â€

Strange, that is, because it’s so full of cliched non-arguments, one wonders what prompted the writer to include it in an otherwise solid piece.

First there is the conflation of two separate things: density and property values. Density does not drive up property values: property values rise when there are more people who want to live in a set location than there are homes to buy. New density may make a place more desirable to live in, in which case more people may want to live there, and if demand rises more quickly than supply, home prices rise too. We know that it’s possible to create density which drives down property values (think about the awful public housing towers of the 1960s), by making a place somewhere fewer people want to live. We have a term for this well-proven process: supply and demand.

Second, there is the unchallenged hyperbole: “dizzying amounts of increased density†as if we ought to reel in vertigo at the mere thought of condo towers.