Insight Into Cities: Looking At What We Value

< source: www.planterart.com >

< source: www.planterart.com >

Green Infrastructure is a key element of cities. Plus, Green Infrastructure affords everyone an interesting lens through which to view the city.

For example: Green Infrastructure provides multiple, reinforcing benefits across scales and space. Urban tree canopy provides benefits far exceeding costs, including intercepting and absorbing particulate matter air pollution, cooling surrounding areas, intercepting and slowing precipitation, conserving energy by shading building envelopes , increasing residential and commercial property values, providing restoration from stress and urban conflict , to name a few.

< source: www.planterart.com >

Yet we strangle Green Infrastructure at every opportunity, despite the services provided for free. Don’t believe me? Check out this interesting photo series. What has been happening in Europe is finally reaching our shores, with a hemispheric twist. What does this series tell us about our priorities? What does it say about technological optimism? How do economic paradigms fail when considering Green Infrastructure as a public good?

The Roosevelt Rezone Dustup: Simple Issue Uncovers Complex Questions

Only in Seattle does a seemingly benign rezone proposal in a relatively sleepy area for development raise discord that rises all the way to the top of a City Hall agenda. In a City facing major, vexing policy decisions (such as not-to-be-named transportation projects), the proposed rezone itself should be a relative no-brainer, if there is broad-based support for the underlying policies driving the process.

On its face, the rezone plan is a logical, diligent, response to local initiative and adds additional capacity around a future transit station. The degree to which many diverse, pro-sustainable development interests have come out against a SEPA DNS (repeat: since when does anyone pro-development oppose a DNS?) for a rezone nonetheless, suggests that adjustments to several key planning policies may need some consideration.

Roosevelt is one of the few places in town where a neighborhood group has supported adding density and, although minor in scale, changing some single-family zoning to more intense uses. DPD, meanwhile, has published a very thorough analysis of the rezone, painstakingly documenting the rationale for each of the rezone changes in light of current City policies. While the rezone adds just 20% more zoned capacity (according to the analysis), the rezoned capacity would amount to approximately 2,000 new units, which, until the Roosevelt Station opens in ten years and provides 15-minute service to downtown Seattle, is plenty of capacity for now.

The most likely outcome of this rezone debate will be moderately increasing maximum heights to 6-8 stores between 12th and 15th Avenues, and between 65th and 66th, but stopping short of the locally reviled “towers†with 125’ heights as proposed by the Roosevelt Development Group. Much of the remainder of the proposal will likely remain intact.

The more interesting aspects of this debate are the ongoing subplots that typify broader Seattle land use policy questions. These include:

- How do we successfully balance the need for local participation in planning with a balanced regional growth perspective? The Roosevelt debate pits neighborhood stakeholders (largely existing residents) with those who arguably are supporting the interests of future residents, and, generally speaking, “smart growth†principles that are valuable to a much broader group of stakeholders. Should the 2012 Comprehensive Plan update seek to re-examine the degree to which land use planning power is vested in neighborhood plans?

- How can we better balance planning considerations with market realities? Good planning tends to capitalize on market trends with positive externalities, rather than attempt to drive a market that is not viable. Many of the proponents of increased density above the planned rezone capacities seem to think that all additional zoned units of capacity are equal, be they mid-rise stacked flats, high-rise stacked flats, townhomes, or single family homes, with each added unit of capacity reducing demand for units elsewhere, presumably in sprawling suburbs. However, these products all have different supply and demand dynamics. Seattle may in fact have plenty of development capacity for small, vertically stacked units but a shortage of affordable larger units (this speculation is a good subject for another post). If that statement was in fact true, adding larger units via “L†zones would tend to reduce sprawl more than adding capacity in vertical development above 65’. Is there a way that we can better align market realities, zoned capacities by unit type, and growth targets that are embedded in City policy making as directed by the Growth Management Act?

- Is Seattle ready to consider any major changes to single-family zones? The Roosevelt rezone debate is being played out against the backdrop of policies favoring the near-absolute protection of single-family zoned areas, focusing debate at on adding additional height in areas already zoned for mixed-use and multi-family. Some additional heights in these areas are sensible, anchored by strong urban design principles and market support. However, keeping 65% (at last estimate) of the City’s total land mass locked up in single-family zones places an incredible burden on mixed-use zones to build out to perceived maximum densities. The cottage housing ordinance was a step in the right direction, but figuring out how to yield more units, particularly two and three-bedroom units, in areas within easing walking/biking distance of transit stops will require a re-visitation of single-family zoning policies. What other rezoning criteria could be enacted that would revitalize and support moderate density neighborhoods while adding to the City’s stock of 2-3 bedroom units near transit?

>>>

Chris Fiori is a Senior Project Manager at Heartland, LLC, a real estate consulting, investment, and development firm based in Seattle. Chris is a Roosevelt-Ravenna resident, and recently finished serving on the Seattle Planning Commission.

Disclosure: Heartland manages an LLC that currently owns a Roosevelt-area development site.

On Tuesday both Mayor Mike McGinn and Councilmember Tim Burgess sent letters (pdfs here and here) to the director of Seattle’s Department of Planning and Development (DPD) asking that the proposed rezone for the Roosevelt neighborhood be reworked to allow for greater heights and densities.

Here’s the KOMO news headline: “McGinn pushes city for taller height limits near Roosevelt light rail.” Am I dreaming?

This may seem like a big yawn, though not if you are familiar with the context. Because what McGinn and Burgess have done is to publicly defy the will of a well-organized, proactive neighborhood group—an almost unheard of move in Seattle politics. But indeed, it’s just the sort of leadership Seattle needs a lot more of when it comes to planning for our light rail station areas.

In 2006 the Roosevelt Neighborhood Association (RNA) handed DPD their completed neighborhood plan update, which included the proposed station area rezone currently in question. Then for four years the rezone effectively sat on a shelf (some speculate that the Nickels administration believed it was inadequate and privately put the kabosh on it).

In 2010 the RNA plan was dusted off and began chugging through the process to the point where a Council vote was expected this summer. And it did not go unnoticed that the proposed rezone is insufficient for a high capacity transit station area.

One might expect Councilmember Sally Clark, chair of the Committee on the Built Environment, to provide leadership on the debate, but she has kept quiet. Considering the neighborhood orientation of Clark’s political base (she once worked for the Department of Neighborhoods), and given that she’s up for election this Fall, this is not a shocker. In contrast, Tim Burgess—also up for election—is much more aligned with the downtown business community, and so has less to lose by saying “no” to a neighborhood.

Regarding rezones in Seattle’s light rail station areas, the ones to also keep an eye on now are Beacon Hill, Mount Baker, and Othello. The recently completed draft Urban Design Frameworks include the latest rezone recommendations, which will be moving to Council in late Summer. So far, there has been no backsliding on the preferred upzones that came out of the neighborhood planning process, but future push back from the neighborhoods should not come as a surprise to anyone.

Getting past such resistance will hinge on Seattle’s political leadership acting in accordance with the point of view that Burgess nails in his letter: “I have been very concerned that the City is not adequately addressing density opportunities near our transit station areas… I don’t want to wake up in 15 or 20 years and find ourselves asking, ‘Why didn’t we properly plan for density in these areas?'”

The Value And Limits Of Neighborhood Planning

Reprinted below is a letter calling for leadership from Mayor Mike McGinn on the need for a more robust planning process in Seattle’s Roosevelt neighborhood, the site of a future light rail station. The letter was written by a coalition of urban planning advocates called Leadership for Great Neighborhoods, and includes signatures from residents, as well as representatives from the Cascade Bicycle Club, Futurewise, Transportation Choices Coalition, the Greater Seattle Chamber of Commerce, and the Seattle Downtown Association. Whenever you have disparate groups such as Futurewise and the Chamber on the same page, it’s a good bet there’s something to the issue.

In short, the concern is that the the proposed upzone currently being considered by the City is insufficient to enable the level of development appropriate for a neighborhood with a regional, high-capacity transit station (see related posts here, here, and here). If you wish to add your signature to the letter, please use this Google form, or contact leadershipneighborhoods@gmail.com.

This circumstance also highlights a contentious debate over the role of local residents in planning decisions that have impacts beyond the local sphere. The groundbreaking neighborhood planning process conducted by the City of Seattle during 1990s is nationally recognized as an urban planning success story, and the Roosevelt Neighborhood Association (RNA) was actively involved. In 2005 RNA was successful in convincing Sound Transit to move the planned light rail station from the freeway into the heart of the neighborhood, and soon after, under their own initiative, RNA completed a neighborhood plan update that includes the upzone currently under consideration.

Overall, RNA has been an inspiring model for how neighborhood residents can become meaningfully engaged in the planning process. But unfortunately, their proposed upzones do not pass scrutiny when factoring in the importance of creating high-performing transit-oriented communities for the region. And this is not the biased opinion of shills for development—it is the broad consensus of urban planning professionals and sustainability experts nationwide (start here for information that supports that claim).

What this demonstrates is that while we all value public participation in the planning process, we also must face the fact that there is a limit, and that decisions of regional consequence should not be left entirely up to local residents. In the case of Roosevelt, this means that—as described in the letter below—the City of Seattle needs to step up and commit a level of planning resources commensurate with the important role the Roosevelt station area should play in helping the City and region achieve their stated sustainability goals. It means Seattle’s leaders have an obligation to make sure land use decisions benefit not just the neighborhood, but also the greater region, and in a very real sense, the entire planet. Achieving urgently needed, systemic progress towards regional sustainability and climate stability depend on it.

Letter after the break, pdf here.

>>>

[ Disclosure: My employer, GGLO, is a consultant to the Roosevelt Development Group—Citytank has no financial ties to either.]

Wait, Maybe There Really Is A War On Cars

Judging by the data, members of the Church of the Automobile might well believe there is a war on cars. How else to explain the unprecedented wane in driving that’s been observed both locally and nationally over the past half-decade?

The Sightline Institute’s Clark Williams-Derry has been digging into the data on driving throughout the Pacific Northwest, and what the data consistently say is that the era of ever-increasing vehicle miles traveled (VMT) is over. A summary:

- Seattle: Per capita VMT down by an estimated six percent since 2005

- SR-520 bridge across Lake Washington: Traffic volumes flat for two decades

- I-90 bridge across Lake Washington: Slight decrease in traffic volume over the past decade

- I-5 Columbia River Crossing: 2010 volumes “just a hair above what they were in 1999”

- I-5 Ship Canal Bridge in Seattle: Seven percent drop in total VMT between 2003 and 2009

- Washington and Oregon (federal data): Seven percent decline in per capita VMT between 2004 and early 2011

- Washington State: Eight percent decline in per capita VMT from 2000 to 2009

- King County, WA: Ten percent decline in per capita VMT from 2000 to 2009

- Greater Portland, OR: 12 percent decline in per capita VMT between 1996 peak and 2009

The national trend is similar (check out this graph). While the rapid VMT decline in 2008 was largely a result of the recession, a clear slackening trend began well before that. Since 2009 total VMT have risen again, but in March 2011 (latest data available) VMT are down 1.4 percent from March 2010, suggesting driving may plateauing again.

As of a few days ago, the U.S. average price for gasoline was $3.81 per gallon, up from $2.76 a year ago. It’s not hard to guess which way this will push the VMT trend. And given the increasing global demand for a limited supply, a continuing upward trend in gasoline prices over the long term is inevitable.

The interesting thing about this mega-shift in transportation is that it’s happening all by itself, with essentially zero government intervention. In fact, given our ongoing penchant for road building, along with our continued subsidization and absorption of externalized costs, you could say that the trend toward reduced driving is happening in spite of our attempts to prevent it.

Imagine how things might go if we actually enacted effective policy and made significant infrastructure investments to facilitate the transformation away from auto-dependence.

What if the State of Washington took a few billion away from freeway projects and pumped it into transit? Which, given the VMT reduction goals codified in Washington State law, is just the sort of strategy one might assume the State would be seriously considering. Oh well, maybe next decade.

The people are already demonstrating their changing preferences, as revealed in the latest data on driving. Governments have an obligation to be more proactive about getting out ahead of the trend to help create the changes that fit the demands of an evolving populace and planet. No war required.

< Winner of the Icelandic High-Voltage Electrical Pylon International Design Competition >

As a function of the work I’m doing now, I’m reading energy trade magazines. EV World recently announced still another power pylon design competition in Europe. Did you know that several European countries have developed or are developing artistic standards for high-voltage transmission towers? That’s right: France, Italy, Sweden, Finland, The Netherlands, Britain, Germany, and Iceland are in some stage of development and implementation of projects to rid their countryside of this ubiquitous visual blight.

< Italian design competition winner >

Here in Colorado, public and private protest over a transmission line to carry electricity generated from solar power in the San Luis Valley effectively delayed development of an industrial solar facility there. Can you imagine how many fewer protests there would be if our electricity infrastructure was actually attractive? What does this tell us about the priority of quality of life in other societies?

>>>

Dan Staley is an urban planner specializing in green infrastructure on Colorado’s Front Range.

In order to remain prosperous, relevant and successful in an increasingly global world, cities must constantly adapt socially, economically, and physically. To paraphrase the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, the only constant in life is change. Humans have known this for thousands of years. So why does the prospect of change in our city—Seattle—and its neighborhoods provoke so much anxiety and ultimately counterproductive resistance?

The extension of a bike path results in a law suit, and proposed neighborhood up-zones near billion dollar transit investments are fought vehemently, resulting in vacant lots and boarded up houses rather than much needed urban housing. Too often, vocal opponents with targeted issues are allowed to dominate our public dialogue, and the city as a whole suffers.

The point is not that all change is good. Clearly, there are choices to be made. However, we should recognize that not only is change inevitable, in many cases it is a direct result of Seattle’s continued growth, vitality and success. There is always room for intelligent debate about what form change takes, but to simply wish for the city to remain as it is (or return to what it was) is both unrealistic and a recipe for mediocrity and a slow civic death.

We live in a city where people choose to move to attend college or start a career, a family, or a company. Plenty of other cities, like Detroit or Cleveland, would love to have our problems. Rather than expend our collective civic energy trying to prevent change, we should embrace our area’s growth and evolution and direct our energy towards becoming the most successful 21st Century city possible.

>>>

Gabriel Grant is a Vice President at HAL Real Estate Investments and Allegra Calder is a Senior Policy Analyst at Berk and Associates.

There are people among us who are waging a war, make no mistake, baldfaced or otherwise. Self-righteous ideologues, they seek to impose their unorthodox values on innocent, upstanding Americans. And the malignant belief that drives their insatiable thirst for war is this: that the hyperbolic rhetoric of “war” has no place in intelligent debates over public policy.

In their most recent assault, this below-the-radar but sinisterly powerful group tapped their deep connections to the media elite, publishing a hit piece on the “War on Cars” in Seattle’s most influential weekly newspaper. There is no war on cars, they smugly claim. Just don’t ask them to explain why they backed a Mayor who rides a bicycle. Q.E.D!

>>>

All apologies for the above meta-outburst, a bit of pent up feedback to the infantilism that so often rears its ugly head in debates over creating viable alternatives to auto-dependence in Seattle. Especially when it has anything to do those scary scary things with pedals and two wheels. And considering the meaning of today’s holiday—Memorial Day—the use of “war” to describe something as benign as painting bike lanes on a street is all the more profane.

This is not a new tactic for manufacturing outrage—as with the war on drugs—or for hyping total non-issues—as with the war on traditional marriage or the war on Christmas. The “war” meme has also been overly applied to projects that are actually challenging and important, such as the war on poverty.

But there are, of course, some situations in which “war” is both an appropriate word and a justified approach. And with all due respect to Memorial Day, here are two matters that I believe ought to be treated like wars in the most genuine sense of the word:

- A war to prevent the continued conversion of our planet into a place unsuitable for healthy human habitation, and to restore it to the beautiful, life-sustaining condition that was originally bestowed upon us. While climate change is not the only environmental problem that matters, it is—no hyperbole necessary—the biggest threat humanity has ever faced. If we don’t start treating it like a war, we will lose, and badly.

- A war to stop the ongoing transfer of wealth and power to a tiny elite minority. History is practically grabbing us by the throat and screaming in our faces that this is the way societies always progress unless the majority stays conscious and takes action to counter it. And we all know that if current trends continue it will ultimately lead to untold misery for the vast majority of human beings on the planet. This war is well under way, but the giant—that is, the bottom 99.99 percent—is still sleeping.

In reality, both of the above wars are manifestations of a single, underlying war, and that’s the war within ourselves, a war humans have had to fight since we became human. It’s a war between our higher capacities for compassion, self-sacrifice, courage, and creativity, and our opposing capacities for selfishness, greed, fear, and laziness. Truly the war that could end all wars.

Roosevelt Environmental Benefits Statement

Since last summer my employer, the integrated design firm GGLO, has been a consultant to the Roosevelt Development Group on their plans to redevelop properties near the future LINK light rail station in Seattle’s Roosevelt neighborhood. As part of this work we developed a new tool for promoting sustainable development called an Environmental Benefits Statement (EBS).

Since last summer my employer, the integrated design firm GGLO, has been a consultant to the Roosevelt Development Group on their plans to redevelop properties near the future LINK light rail station in Seattle’s Roosevelt neighborhood. As part of this work we developed a new tool for promoting sustainable development called an Environmental Benefits Statement (EBS).

The Roosevelt EBS was intended to be a resource for informing the ongoing debate over upzones in the Roosevelt station area (background here and here), and I encourage people to download the full document.

In general, the purpose of an EBS is to articulate the wide range of economic, social and environmental benefits that can be provided by thoughtful development. Unfortunately, the controversy that often swirls around proposed development has a tendency to overshadow the potential benefits. Furthermore, large-scale development projects usually require an Environmental Impact Statement, a document that tends to frame the public debate in terms of the potential negative impacts.

An EBS helps balance the discussion by focusing on the positive; it elucidates the full range of economic, social, and environmental benefits that responsible development can provide; and it holistically focuses appropriate attention on all there is to be gained—at the neighborhood, city-wide, and regional scales.

As described in the Roosevelt EBS, the impacts of land use decisions around the future Roosevelt light rail station extend far beyond the boundaries of the neighborhood. At the same time, there is an opportunity for well-designed development to result in a win-win for the neighborhood and for the greater region.

The critical enabling component in all this is zoning that allows enough height and density to fully leverage the benefits offered by the transit investment. And while the Roosevelt Neighborhood Association’s upzone proposal currently being assessed by City planners is a step in the right direction, it is not enough. And if you want to know why, it is all spelled out in the Roosevelt EBS.

Lastly, if you think this is important and have an opinion, please email your comments to city planners Shelley Bolser (shelley.bolser@seattle.gov) and Geoffrey Wendtlandt (geoffrey.wentlandt@seattle.gov) at Seattle’s Department of Planning and Development. Your comments matter.

Let’s Get Roosevelt Station Area Land Use Right

Recently, Futurewise told the Seattle Department of Planning and Development (DPD) there would be a significant impact on the environment if it did not allow more development.

You ask, “The state’s premier advocacy group for holding local governments accountable to environmental land use laws did what?â€

For the average Washingtonian who probably thinks that environmentalists are always fundamentally against development, this may come as a surprise. So I think Futurewise’s recent letter to DPD regarding the Roosevelt station area merits further explanation.

First, a little background.

In 2008, the voters and taxpayers of the Puget Sound region passed “Mass Transit Now,†a ballot measure that raised billions of new taxpayer dollars to build an extension of the Sound Transit Link light rail system to the south, east, and north from the Phase I of the Link line.

Given the previous failure of the “Roads and Transit Act†in 2007, which was opposed by the Sierra Club and other environmental groups, I don’t think it’s too far of stretch to conclude that voters and taxpayers approved the “Mass Transit Now†ballot measure in order to achieve a range of shared goals, including reducing global warming pollution, providing better transit, spurring economic development, and creating livable neighborhoods.

Through the 2008 transit-only measure, the region’s taxpayers chose to invest $1.4 billion in the north-end corridor that connects Downtown Seattle to Northgate with three stops: the University District, the Roosevelt neighborhood at 12th Ave and 65th St, and Northgate. In anticipation of light rail, a station area upzone process was conducted for the Roosevelt station area, and recently DPD had to decide whether the proposed upzone would have a significant impact on the environment.

Unfortunately, from Futurewise’s perspective, DPD said the upzone wouldn’t. I say unfortunately because the planned upzone is inadequate for achieving the regional taxpayers’ goals and vision for the Link light rail and their accompanying station areas.

In a time of constrained public budgets, it’s imperative that we maximize every dollar spent for our common goals and vision. For our region, the goals that rise to the top include addressing climate change, saving local farms and forests from sprawl, protecting clean water, expanding more transportation choices, providing more housing opportunities, and building vibrant, walkable neighborhoods in which small businesses can flourish. If we do the planning correctly now, the Roosevelt neighborhood can easily be part of that vision.

Transit investments are leveraged most effectively when combined with opportunities for more people to live, work, and meet their daily needs within close proximity to stations. To a large degree because of the investment in the Link light rail, the Seattle Planning Commission’s recent Transit Communities Report identified many of the neighborhoods along the north-end alignment as ideal for more development and infrastructure.

But in some areas as close as one block from the Roosevelt light rail station, the proposed upzone would constrain the developable capacity to single-family zoning. And much of the commercial zoning within a 5-minute walk of the station would be limited to 40 feet in height. These constraints would lead to a major wasted opportunity to help solve our region’s biggest environmental problems.

It is critical that Seattle planners and elected officials thoughtfully evaluate all land use decisions in future station areas. That’s why Futurewise asked DPD to reconsider its initial finding that the rezone to the station area would not have a significant impact on the environment, and to instead undertake a comprehensive station-area planning effort as a high priority to ensure our communities continue to grow into thriving, high-value neighborhoods that benefit the immediate community, Seattle, and the region.

As light rail is built out, station areas like Roosevelt will offer unmatched opportunities for achieve the region’s goals and vision. Seattle must not hinder our capacity to achieve the region’s desire for more people to enjoy a higher quality of life with more home, business, job, and transit choices.

>>>

Brock Howell is the King County Program Director for Futurewise, a statewide public interest group working to promote healthy communities and cities while protecting farmland, forests and shorelines today and for future generations.

Passivhaus Could Have Made Bullitt Foundation Living Building 35% More Energy Intelligent

< Rendering of the Bullitt Foundation's Cascadia Living Building; image courtesy of The Miller Hull Partnership --- click to enlarge >

If the Bullitt Foundation’s Cascadia Center Living Building had been designed to meet Passivhaus, it would have needed only two-thirds of the on-site-generated energy of the current design to reach net-zero. In other words, a much smaller photovoltaic array.

The Cascadia Center for Sustainable Design and Construction (website for the building) is likely to be the second building in Seattle to meet the Cascadia Green Building Council’s rigorous Living Building Challenge. Designed by Seattle starchitects Miller|Hull, with mechanical engineering by Portland’s PAE Consulting Engineers with input from the Integrated Design Lab, the building is a marvel of sophisticated active technology and expressed greenness. Motorized windows open automatically to provide cooling. Computer-controlled shades raise and lower to help maintain optimum lighting levels. Deep borings below the building tap geothermal warmth. A prominent stair with spectacular views encourages tenants to skip the elevators. There is no parking garage! (But there is bicycle parking!) A (very) large, controversial photovoltaic “hat” tops the building. (Some call it the “comb-over.”) As stated on the building’s website, the Bullitt Foundation expects it to be the most energy-efficient commercial building in the world.

But will it be?

I was curious about how Cascadia Center might compare with Passivhaus, in terms of its energy intelligence. After the public presentation of the building at Benaroya Hall I emailed Scott Wolf of Miller|Hull and Denis Hayes, asking if I might have information on the building necessary to make a comparison with Passivhaus. Denis responded that he would be delighted to cooperate, and Scott put me in touch with Brian Court, the project architect, and Jim Hanford, sustainability lead, both of Miller|Hull. I am grateful to each of them for facilitating this conversation and supplying the area take-offs and EUI for the current design. Before we get into the numbers, if you aren’t familiar with Passivhaus, you might want to click over to the introduction to Passivhaus on my website and back.

Basis of the Calculation

- The gross square footage of the building is 52,000 SF.

- The Treated Floor Area (based on the German DIN 277-2 method) is 39,050 SF, or 75% of the gross area. Treated Floor Area (TFA) is used in calculating energy use allowed in a Passivhaus building.

- The Energy Use Index (EUI)Â of Cascadia Center is 16. EUI is total annual energy use divided by gross square footage.

- The limit in Passivhaus for Primary (Source) Energy is 38 kBTU/SF/year.

- In Passivhaus, an energy factor is applied to various forms of energy to account for generation and transmission losses. For electricity, this factor is 2.7.

Solving for an EUI that would meet Passivhaus:

38 kBTU/SF/yr ÷ 2.7 = 14.07 kBTU/SF/yr. (This gives us an annual Primary Energy usage target, taking the electrical energy factor into account.)

39,050 SF (TFA) x 14.07 = 549,434 kBTU/SF/yr (This gives us the site annual energy usage using TFA for a building that met Passivhaus.)

549,434 kBTU/SF/yr ÷ 52,000 (GSF) = 10.57 (This gives us the EUI target for a building that meets Passivhaus.)

The current EUI of Cascadia Center is 16. To meet Passivhaus, the EUI would have to be 10.57.

10.57 ÷ 16 = .66

A building that met Passivhaus would use 66% of the energy of the Cascadia Center as currently designed. Had the building been designed to meet Passivhaus, the photovoltaic array could have been two-thirds its current size. This has dramatic implications for future buildings seeking to meet the Living Building Challenge.

Or, looking at it the other way:

52,000 GSF x 16 (current EUI) = 832,000 kBTU/yr (total annual Primary Energy usage)

Solve for kBTU/SF/yr using TFA.

832,000 kBTU/yr ÷ 39,050 SF (TFA) = 21.3 kBTU/SF/yr

Multiply that by 2.7 (the energy factor for electricity) to get the primary (source) energy usage.

21.3 kBTU/SF/yr x 2.7 = 57.52 kBTU/SF/yr

Passivhaus requires an annual primary energy usage (source energy) of 38 kBTU/SF/yr.

57.52 ÷ 38 = 1.51

The building as designed exceeds the Passivhaus standard for Primary Energy by a bit over 50%. That’s worse than my Passivhaus colleague Mike Eliason of brute force collaborative calculated using guesstimates of TFA from the permit documents filed with DPD.

We know that it is possible to reach Passivhaus with this building type, because there are many examples of similar buildings in Europe that meet Passivhaus (see image above), all of which would have a lower EUI than Cascadia Center if you don’t count the energy generated on site by the photovoltaic array. Therefore, it appears the Cascadia Center will not be the most energy efficient building in the world.

I suspect we may see something interesting if we look closely at the air leakage, and compare Miller|Hull’s target with Passivhaus’s 0.6 ACH@50 Pascal. Proportionally the ventilation and pump energies seem high, but once all other loads are reduced, those loads might pop out more, and utilizing on-site water (to meet Living Building Challenge) requires pumping. If they were starting from scratch, it may be that by concentrating first on the siting, building massing, envelope assemblies and air-tightness (as one does in the Passivhaus design process) they would have been able to eliminate the need for some of the mechanical systems. With the internal heat gain of a typical office building, and an appropriate wall assembly, air tightness and glazing, heating load ought to go to zero, and with proper shading (as they’ve done already) cooling load should get to close to zero as well.

Ironically the featured stair, intended to encourage walking over using the elevator, contributes to the building missing the Passivhaus mark. As circulation space, it is not counted in the Treated Floor Area, so has the effect of reducing the total kBTUÂ available for use annually while still meeting Passivhaus.

Despite not meeting Passivhaus, Cacadia Center is a brilliant, important building. That it will be possible to better it with simpler, less expensive, less complicated and more durable means is encouraging. Since we already see dramatically lower energy use with existing Passivhaus buildings, it is clear that Passivhaus is a proven and better way to meet the “Energy Petal” of the Living Building Challenge than the active technologies employed in the design of the Cascadia Center.

>>>

Rob Harrison, AIA, is a Seattle architect and Certified Passive Houseâ„¢ Consultant. This article originally appeared in the Harrison Architects blog.

The video below shows what its like to bike commute through Capitol Hill on a typical evening in Seattle. Traveling east on Pike Street, there is no bike lane or sharrow, but it is a popular route nonetheless—I’ve ridden it more than a thousand times, no exaggeration.

My guess is that to a sizable chunk of the populace, riding through the city in a scenario such as the video shows is not an appealing prospect. Here’s my mom’s Facebook comment:

Did you film that? I was getting nervous watching it and then realized that was probably you right behind in that traffic, and wished I hadn’t looked at it. Don’t need first-hand experience of the dangers.

Tell me, is it crazy to do a commute like that on a regular basis? I’m not a good judge because I’m so used to it (sorry mom, I shot the video riding with one hand as I held the camera in the other).

As I wrote in the previous post, the most powerful deterrent to biking in the city is the safety risk—both real and perceived. But we know very well how to design streets that ameliorate that risk. It doesn’t cost very much and it typically has little impact on car travel. All that’s missing is a shift of priorities. And though City of Seattle government has been making progress, as a community we still have a long way to go.

Why I Ride A Bike (Not That You Asked)

No, it’s not because I’m trying to save the planet. It’s because I’m selfish.

I bike commute between the Central District and downtown five days a week, all year long, and I also ride occasionally to do errands or go out. And I do it because biking is, for a whole pile of reasons, simply the best way for me to make those trips.

My top six, selfishly practical reasons:

- Bikes are cheap to buy, cheap to operate, and cheap to park. And I’m cheap.

- Riding is exercise, and like many of us I find it incredibly hard to make time for exercise if it’s not integrated into my daily routine.

- Biking is much faster than walking, and for my commute it’s also faster than the bus, even though the bus stop is only three blocks from my house.

- I avoid the frustration of not being in control: I never have to wait for a late bus, I can go around cars stuck in traffic, I can stop and take a picture whenever I want.

- It’s exhilarating—I always feel more alive after a ride, even when the weather’s miserable.

- It’s just plain fun to zip around on the city streets—sometimes I practice riding wheelies like a 12-year old on my way in to work.

As you see, it’s all about me. To me, biking is such a perfect choice for urban mobility that the real question is: why do so many people not ride? Which is a far more interesting question than why I do.

Yes, there are those who cannot ride for good reasons, such as being physically incapable, or because they have lots of stuff to take with them, or because of challenging logistics. But there’s no way that adds up to 97 percent of commuters in Seattle.

Is it because people are too out of shape? I’m no superjock—I’m a middle-aged guy who sits in front of a computer screen all day and does a little yard work occasionally. It’s really not that physically hard to ride a bike a few miles, is it? And anyway, aren’t we Seattleites supposed to be all wholesome and fit like the people in the REI catalog?

Is it the hills? It’s true, biking up hills can be a drag. But on the other hand, as a biker who thinks it’s a good thing to get some exercise from my ride, I’m actually thankful for the hills. And hills are also fun to roll down. And hills give you nice views. Why is everyone so wimpy when it comes to biking the hills in Seattle? Don’t tons of people move here because they see themselves as tough outdoorsy mountain climber types? Doesn’t everyone want a convenient way to keep their legs in shape for next snowboarding season? Apparently not.

Is it the weather? For sure, Seattle’s winter weather is soul-sucking. But hey, at least it’s not Chicago, or dozens of other cities where gets so cold it hurts to be outside. And at least it’s not Houston, or dozens of other cities where you step outdoors in summer and you’re instantly drenched in sweat and can barely breathe. Seattle’s climate is temperate. That means it’s fairly comfortable to be outside on a bike all year long.

And the rain? Based on my observations, if I didn’t know better I’d assume that there’s a city ordinance requiring every Seattle resident to own a full Gore-Tex suit. And the thing is, it’s actually pretty easy to slip those on and ride a bike and stay dry. And even if you get a little wet once in a while, well you know, it’s only water.

Is it a case of people being unfamiliar with an option they haven’t tried? Could be—recall the stories of people who rode the bus for the first time when gas prices were high, only to discover that it’s a pretty nice way to get to work. But jeez, are there really that many people out there who are not willing to try something new? Sad, if true. Most of us grew up riding bikes (and you never forget how once you learn).

Culture? Sure. We are a society with a deeply rooted love of cars, and let’s face it, bikes are pretty unmanly in comparison. But culture is malleable, and my sense is that the car’s grip on our collective psyche is loosening, and that shift is going to happen in the cities first. Peruse this for a preview.

What about time? Not everyone lives two miles from work like I do, and as the distance increases, the time advantage of biking dwindles and eventually goes negative. Time is money: I get it. However, that equation probably doesn’t flip as quickly as many people think, once you account for the time it takes to get to and from the bus stop, or time spent finding parking and getting to and from the parking lot. And then there’s time saved not going to the gym. And also the interesting twist that when you consider the health benefits, the extra time it takes to bike is likely repaid several times over in increased life expectancy.

The last reason standing is safety. It’s the most legitimate, rational reason not to bike, hands down. Unlike the other reasons discussed above, there’s little a rider can do about it, because the majority of the risk is posed by cars. And changing that is going to take serious investment in cycling infrastructure, along with driver education and stricter laws. You know, like they have in Europe. Where they bike a lot.

And finally, it’s important to remember that we don’t need to make those changes just to please bikers like me. Because it just so happens that things that are good for people are quite often also good for the planet.

>>>

Note: This piece was originally published on PubliCola last Fall. I’m reposting it here in recognition of Bike To Work Day.

>>>

Last weekend I was chaperoning three elementary-school-age kids and needed to do some shopping in downtown Seattle, two miles from home base in the Central District. What was our travel mode of choice? The automobile.

Yes, by car, even though there’s a bus stop two blocks from my house with a line that would have taken me to within two blocks of my downtown destination. What gives?

My first thought was to take the bus, mainly because parking downtown is known to be an expensive hassle. But then a vague memory bubbled up about low rates at the city-owned parking garage at Pacific Place, and I found out it would cost $7 to park for two hours. Not much more than the $4.50 bus fare for my crew. Factoring in the time and convenience, along with the negligible gasoline expense, the car was the easy winner.

So it goes. We Americans are incessantly trained pretty much from toddlerhood on to be skilled consumers, that is, to make purely rational, cost-benefit-based decisions. And not surprisingly, that’s how most people typically make their transportation choices.

The problem is, because a significant portion of the costs of driving are either subsidized, or externalized and borne by society as a whole, the deck is stacked in favor of driving. It’s a market failure that leads to lots of people making choices that seem to be in their best interest, but in the end are not, because the whole society suffers—and eventually the planet calls the bluff.

One simple way to help counteract that market failure is higher gasoline and parking taxes, the revenue from which can then be used to promote transportation alternatives that don’t come with all the detrimental side-effects of cars. Call it reverse social engineering. Because engineering society is exactly what our auto-biased system has been doing for decades.

If I had to pay twice the parking rate, maybe I would have taken the bus. (Of course we’d also have to make sure the “free” commercial parking is taxed so I wouldn’t be tempted by the malls.) Or maybe I’d try to find what we needed at a neighborhood store closer to home. Or maybe I’d go another time by myself on bike.

But here’s a point that bears repeating: Requiring people to pay the true cost of their driving is not an ideological conspiracy to force the innocents out of their cars and into spandex bike shorts. It is, rather, a strategy for establishing fairness and enhancing choice, while at the same time steering the societal ocean liner away from the iceberg and toward a more sustainable path.

>>>

A Pictorial Epilogue:

At Pike and Broadway on the way downtown, a blatant reminder of how deeply entrenched in car culture we still are, even in liberal, green Seattle. Because apparently it is still possible to successfully market a product with a Hummer, the stupidest, most offensive car ever made:

No matter how clean and well lit, underground parking garages are creepy, claustrophobic, and disorienting. They are very expensive things to build, yet they not places fit for people:

Up from the garage and into the mall—such a family friendly place! See those pretty people in the picture kids? By the time you are 12 you better look just like them or you are worthless:

It was a nice day last Saturday in Seattle, and the downtown retail core was packed—I wasn’t the only one willing to pay the cost of parking. It was inspiring to see so many people out walking on the big wide sidewalks—yes, Seattle does have some real urbanism. And the energy that real urbanism creates is a big advantage downtown will always have over the malls. For example, you would never come across the scene below in a mall parking lot. My kids wanted to know what marijuana is. They learned something about real life:

At Pacific Place, you pay for your parking in style. No fumbling around for your money in the front seat while the bored gatekeeper waits in a dingy booth. In fact, the Pacific Place pay area has actually become a well known meat market for singles on the hunt. Alas, but then you still have to drag yourself back down into the concrete bunker and find your way out of the labyrinth:

How Much Density Is Too Much Density?

Since returing home from my research trip to Hong Kong, I keep finding myself coming back to this picture:

And though the image does showcase the vast density of Hong Kong, it can’t possibly convey the true feeling a person experiences when witnessing this first hand. Even having been in Hong Kong for a couple of days, this sight really did leave me speechless.

And the numbers back up that impression: Hong Kong has a population density more than twenty times higher than Seattle’s.

Seattle, like an increasing number of U.S. cities, has begun to prioritize infill and transit-oriented development. The hope is that larger numbers of people living closely together allows for amenities within walking distance and the potential for more environmentally sustainable living where people can make trips by on foot or by taking public transit.

But, can there be a thing as too much density? While there are many proven benefits to dense urban environments, there is also the potential for negative externalities. A report from Demographia points out the world’s most densely populated cities generally score poorly on the prosperity scale (when focusing on price and income). Hong Kong while ranking 42nd in population was 3rd in density at roughly 66,000 people per square mile. For comparison, Bangladesh has 90,000, Mumbai has 70,000, and Seattle is a little under 3,000. However when ranking by gross domestic product, Hong Kong was 16th, Mumbai was 29th, and Bangladesh was in the 70s.

Of course the inverse is not necessarily any more true. Less densely populated cities don’t seem to have a greater chance of being prosperous, so there may not be a direct correlation between prosperity and density.

More data is needed to determine the level of density that is most efficient and sustainable for each unique urban area. However, the readily observable prosperity and livability of Hong Kong makes it clear that cities like Seattle have plenty of room to get more dense before worrying about too much density.

>>>

Marc Weigum is owner of Weigum Properties and an Affiliate Fellow of the Runstad Center for Real Estate Studies in the College of Built Environments at the University of Washington.

Rough Ride: Roosevelt Rezone Creates TOD Opportunity

Seattle’s Roosevelt neighborhood is the ideal place to build the kind of transit-oriented community that many of us hoped would proliferate with the development of light rail. Roosevelt has all the right ingredients: a planned light rail station, proximity to open space, an iconic public school, lots of buses, and a healthy business district. But what it doesn’t have—and may not get any time soon—is zoning that allows development intensity appropriate for a high-capacity transit station area.

The light rail station entrances are going to be located on 12th between 65th and 67th. Most of the land on the three blocks forming a panhandle to the east—between 12th and 15th—are owned by Hugh Sisely, who has been a long-term object of anger in the neighborhood for not maintaining his properties. A few years ago the City got aggressive (after lots of complaints from the neighborhood) with Sisely, fining him $75,000 for numerous violations of the code.

Now Sisely’s development partners, the Roosevelt Development Group (RDG), are looking to significantly upzone the panhandle from its current multifamily and NC 40 designations to 120 feet. They’ve submitted a contract rezone proposal to the City Council.

Meanwhile, the neighborhood has its own plan. The Roosevelt Neighborhood Association is proposing that Sisely’s panhandle blocks on the south side of NE 66th St. between 12th & 14th Aves NE go from “Neighborhood Commercial 1 with a 40’ height limit (NC1-40) to Neighborhood Commercial 2 with a 40’ height limit (NC2-40).” On the north side of NE 65th St, between Brooklyn Ave NE & 14th Ave NE and the NE corner 14th Ave NE and NE 65th St the neighborhood proposes a shift from “Lowrise 2 (LR2) to Neighborhood Commercial 2 with a Pedestrian designation and a 40’ height limit (NC2P-40).”

This puts the developer and property owner at loggerheads with the neighborhood. The neighborhood wants a lid on new development while the developer is proposing significant increases in height (up to 120 feet). Height isn’t the issue in and of itself, however. What matters is density.

The Futurewise Blueprint Transit Oriented Communities for Washington State documents how TOCs come together when there is a high enough concentration of people around the stations. Density of residents and jobs is crucial to sparking a true TOC at Roosevelt.

[An analysis] of the 2001 U.S. National Household Transportation Survey and concluded that given two identical households, if one is located in a residential area with 1,000 more dwelling units per square mile (1.6 units per acre) more than the other, the occupants will drive 1,171 miles per year less.

Walking around the future station area it becomes clear that east of the new station there isn’t much opportunity to create more housing other than on Sisely’s property. The stretch of 65th already has good transit connections and would allow links to a node of commercial retail on 20th and 65th. The proximity of Roosevelt High School means there’s no room to grow there, and to the south of Sisley’s properties is more established single family.

We are, potentially, headed for another Beacon Hill, where we have hundreds of millions in regional infrastructure poking its head out of the ground surrounded by parking lots, low rise retail, and single family homes. We can’t let that happen in Roosevelt. It’s true that the neighborhood plan does propose upzones, but the panhandle is especially crucial. The meager height increases for the three blocks are not enough.

Beacon Hill suffered from a lot of contention over upzones around the station. Instead of dealing with those concerns when the neighborhood plan was approved years ago, the Council kicked the can down the road, deferring tough land use decisions for more than a decade. Now the City is playing catch up with rezones that should have happened before the station was built. The Beacon Hill problem can be avoided in Roosevelt by trying out this approach:

- RDG should drop its proposed contract rezone—This would be a compromise since, if their proposal goes through, RDG and Sisely would get 12 stories. They’ve already put a lot of work into this, but it’s not what the neighborhood wants to see happen. They can come back to the table and work with neighborhood on another solution.

- The neighborhood and DPD should hold off on their proposal—The proposal as it now stands simply keeps the Sisely panhandle properties fallow, which is worse than nothing. The boarded up buildings are an eye sore. The community certainly wants more than this:

- The City should facilitate a round of dialogues about the future of these blocks—This process should have a timeline and not be open-ended. Both sides will have to give something up in order to get some benefits. But this is a decision that will impact the neighborhood—and the whole city—for years to come.

- Sound Transit needs to get into the game—Sound Transit has often said that it’s a transit agency, not a land use agency. Fine. But building expensive regional infrastructure and not getting the land use right is wasteful. Sound Transit should help with funds and staff, dialogue, and the solution.

It’s understandable that the neighborhood is not happy with the land owner. And there may even be legitimate disagreements about how high the buildings should go. But this is a chance to make something positive for current residents of the neighborhood and lots more people who would benefit from living and working right next to a major regional transit link. The City needs to hear from people who support density around the Roosevelt light rail station, and soon. You can send your thoughts to the folks at DPD here.

Finally, we have to start aligning regional transit investments with local land use. Spending billions on light rail to connect regional population centers but then leaving the land use decisions to the parochial concerns of dozens of city councils is a formula for failure. Policy and planning should be implemented to ensure that communities directly benefiting from the light rail investment reciprocate by embracing appropriate density.

>>>

A version of this post originally appeared at Seattle’s Land Use Code, an ongoing blog about reading zoning code.

< Rendering of Treasure Island by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill >

What’s wrong with this picture?

The city in the top left is San Francisco, and the polygon of land in the bottom right is Treasure Island, the 400-acre site of what will supposedly be “the most environmentally-sustainable large development project in U.S. history.”

But that, I’m afraid, is a tough claim to swallow when the only terra firma connection this development will have with the outside world is a big driveway called Interstate 80 and the Oakland Bay Bridge. Because no matter how energy-efficient the buildings may be, no matter how pedestrian friendly the urban design, with such an isolated location, Treasure Island is guaranteed be a transportation suck.

Last month the $1.5 billion redevelopment, in the works since 1997, was approved by the San Francisco Planning Commission, and is now awaiting final approval from City’s Board of Supervisors. Plans call for 8,000 housing units (25% “affordable”), three hotels, a retail/commercial center, an expanded marina, a ferry terminal, and about 300 acres of open space (see graphic below).

<Source: Treasure Island Development Authority via SFGate >

Designed with the help of international green engineering superstars Arup, the impressive list of sustainability features includes LEED certification, pedestrian-oriented urban design, on-site stormwater and waste-water treatment, and a target of 50% of energy drawn from renewable sources. It’s already racking up the awards.

The root problem with all this is that Treasure Island is, well, an island. Even with a commercial center, the majority of residents can be expected to drive off the island not only for work, but also to satisfy many of their everyday needs—there won’t be a Costco on the island. Likewise, delivery of all the supplies for living will rely on that single I-80 lifeline. Add to that the fact that it’s built on sketchy soil that could liquify in earthquake, and is likely to be threatened by rising sea levels caused by climate change.

Treasure Island is analogous to an uber-green single family home sited in a remote forest. It’s reminiscent of the ass-backwards new city of Masdar in the United Arab Emirates, touted as “one of the most sustainable communities on the planet,” never mind that it’s located 11 miles from the nearest city in an empty, blazing Arabian desert.

For sure there is value in the high-density, green design that will be implemented at Treasure Island—we will learn a lot from doing it. But to be truly sustainable, a community must be efficiently connected and integrated with the urban fabric of its immediate surroundings, as well as with the greater region. (Seattle’s Yesler Terrace is a good example of such a location, where large-scale redeveloment makes sense.)

Green enclave is a contradiction in terms.

We ought give back the Treasure Islands of the world to the harbor seals, eagles, and trees, and plant people where they belong.

< Rendering of Treasure Island by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill >

What Really Causes Gridlock? Cities Do.

The recently published University of Washington study on the effects of removing Seattle’s Alaskan Way Viaduct on commute times is but the latest data-based rebuttal to claims made by deep-bore tunnel proponents that a surface option would create gridlock.

Comparing a tunnel to a “worst-case scenario in which the viaduct is removed and no measures are taken to increase public transportation or otherwise mitigate the effects,” the UW study predicted a mean increase in commute time of six minutes, and also that “in the rest of the region, on I-5, there’s no indication that it would increase commute times at all.”

And that’s without any of the improvements to I-5, the street grid, and transit service that would be part of an integrated I-5/Surface/Transit alternative.

< Let's Move Forward's pro-tunnel ad trots out the "gridlock" boogeyman >

In recent months tunnel supporters seem to have coalesced on the idea that the “gridlock” meme will resonate with the general public, and they are no doubt correct. The only catch is that the gridlock claim has no basis in fact. No matter though, gridlock is a superb boogeyman, and that’s politics, as the Republicans have taught us well.

But stay with me now, because regarding so-called “gridlock,” here’s a reality that all of us city-boosters need to come to grips with: a dense city without heavy traffic congestion is like a unicorn. That is, it doesn’t exist.

Tunnel or no tunnel, if Seattle densifies to the degree necessary for achieving significant sustainability benefits, all of our key roads are going to become jammed with cars. Road networks have inherent spatial limitations, such that in any urban area with a high density of homes and jobs, the demand for auto trips is guaranteed to swamp the capacity of the roads. It is as close to a mathematical certainty as you’ll ever find in the unpredictable realm of cities.

Once this inevitable end is recognized, the only sane path for moving forward becomes clear: Stop throwing away precious public funds on roads, and instead invest in solutions that give people transportation alternatives. And it just so happens that that path is also one of our most promising strategies to address urban sustainability, and for Seattle, climate change in particular.

Yes Seattle, expect more gridlock in your future (driven on Denny Way on a weekend lately?). It’s coming, whether or not we spend billions on a deep-bore tunnel in a flailing attempt to avoid it.

But that doesn’t mean the downfall of civilization. The solution is to create a city in which people can get around without relying on a car. This includes not only building infrastructure to support walking, biking, and transit, but also creating compact, mixed-use centers that reduce the need for long trips. I have yet to hear a convincing argument for how a 2-mile underground bypass freeway for cars is anything but anathema to that strategy.

It comes down to deciding what a city is for. Is it a place to get through, or a place to be?

Complexity and Cities: Green Infrastructure and Green Buildings

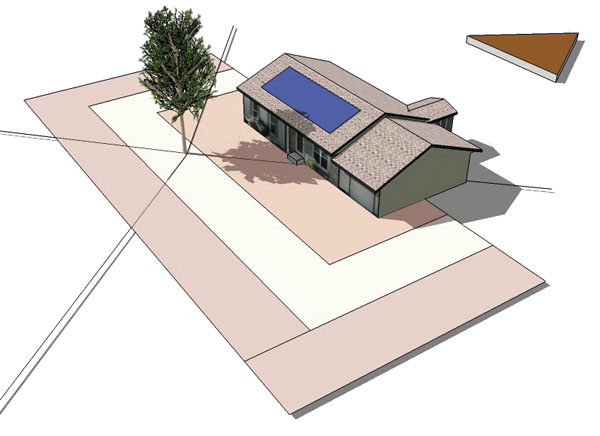

In efficient built environments, we need to ensure roofs have a clear path to the sun, in order to collect sunlight to generate power and heat water. Solar access and good insulation mutually coexist and make for a better, more efficient building.

Ensuring a clear path to the sun can be controversial, especially in America where there is no “right to light.” That’s right: American law does not guarantee access to sunshine (or avoidance of shade). Recent events in California resulted in a compromise that ensures existing solar arrays have a clear, unimpeded solar access plane to the sun from 10:00 a.m – 2:00 p.m. to produce power. This “10-2” window is now an increasingly common default setting for communities looking to implement Renewable Energy Standards or solar access plane legislation (more on this in a minute).

Compare this lack of American law to British Common Law, where a “right to light” has been a given for centuries, and was recently clarified with something called a Leylandii Law. Leyland cypress – Cupressus leylandii – is a popular, fast-growing evergreen plant used for screening unwanted views. But so many complaints of shading by this tree were lodged that a law was strengthened to privilege the right to receive sun over the right to screen neighbors. That is: British citizens by law cannot plant a tree where it would impede someone else’s access to the sun.

Another issue we contend with in our buildings is sometimes having too much sun. A typical response—especially for residential buildings—is to plant trees to shade walls and roofs to cut envelope conditioning costs [1]. Yet these same trees may grow into the solar access plane and decrease power generation as well as create carbon emissions from maintenance activities. For companies that lease roofing space to generate power, trees growing into the solar access plane can be a disaster for both the loan repayment and even for their business model [2].

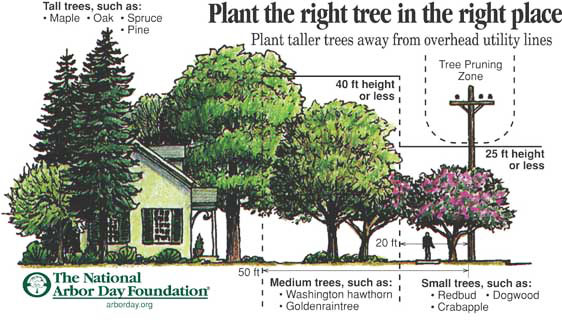

Yet we cannot simply cut down all trees so we can have solar power. Healthy trees intercept stormwater, reduce the urban heat island effect, increase residential and commercial property values, reduce building envelope energy usage, and restore mental acuity among other things. We need trees around us. We simply need the right trees in the right places. The old Arbor Day paradigm of “right tree right place†will be outdated in the modern, energy-producing city:

As you can see, the old paradigm was needed for shade on poorly-insulated buildings, and installing a rooftop solar array means cutting trees and losing their benefits. The new paradigm for trees and buildings will be the opposite – ornamental trees next to buildings, and shade trees away from buildings and over impervious surfaces:

In the picture above, the innermost region is planted only with ornamental trees. The outer regions can be planted with typical shade trees; in this rendering, a 35-foot tall tree is seen at a distance typical for treelawns in modern single-family subdivisions on the equinox at 2:00 p.m. The shade tree still performs important ecosystem services; only above the tree is not shading the solar array.

Similar planting zones should be implemented in the next set of LEED standards. The urban foresters are ready to help lead the way on this effort with their “solar smart practices.” Our tree canopy is too important to sacrifice for renewable, distributed energy—trees and solar energy can work together. It is true that it is likely new housing starts will be in the doldrums for some time to come, but there is still redevelopment activity, and this activity will need proper tree siting. This time, we can make a positive change before it is too late. Right tree, right place, right reason is the new paradigm.

Next up: details on how to grow better green infrastructure in cities, especially parking lots and roadsides.

>>>

Dan Staley is an urban planner specializing in green infrastructure on Colorado’s Front Range.

Picture credits: Arbor Day Foundation, Dan Staley and John Olson.

[1] Trees can also cut heating costs slightly by creating turbulence and slowing wind speeds. This turbulence from trees and buildings is one reason why residential wind is among the least-best options for renewable energy.

[2] Several lease arrangements are currently popular, whereby a company can lease a roof for a flat fee or sell back power to the property owner in exchange for siting photovoltaic arrays. The company invests in the solar panels and labor to install and maintain, often through bank loans, and profits by the difference in savings on grid energy pricing.

< Courtland Place Passive Project in Seattle's Rainier Valley; photo by Dan Bertolet - click to enlarge >

Reducing a building’s heating energy use by 70 to 90 percent can be achieved with three basic ingredients:Â (1) highly insulated walls and windows, (2) a tightly sealed envelope, and (3) heat recovery ventilation. Not rocket science, but common sense applications of the principle of “efficiency first.”

And those are the three key components of “Passivhaus” design, a highly energy efficient building construction standard that has been successfully applied in more than 25,000 buildings in Europe. So far, only a handful have been built in the U.S. You might wonder—as I have written previously—what’s our excuse?

The photo above shows Dan Whitmore’s nearly completed Courtland Place Passive Project, Seattle’s first permanent building designed to the Passivhaus standard (the Mini-B Passive House isn’t a permanent structure).

The mother-in-law unit has been occupied for two months, and according to Whitmore so far the heat was turned on for a grand total of about five minutes on one especially frosty morning in March. Aside from that brief lapse, the excess heat generated by appliances, people, and the sunlight coming through the windows was enough to keep it comfortably warm inside. I can attest that the space was warm, almost too warm, on the partly sunny but cool spring day of the Ecobuilding Guild’s recent green home tour.

And yes, the heat recovery ventilator has to run 24×7 in cold weather when the windows are closed, but it only consumes about as much as a 50 watt light bulb. Whitmore’s house has no furnace—a significant up front cost savings. On the coldest days it can be heated with two small baseboard electric heaters, or by running water from the domestic hot water tank through the heat recovery ventilator.

But is it expensive? A recently completed Passivhaus in Portland reportedly had a 10 percent cost premium over conventional construction (the windows are a major part of that premium). In Germany where contractors have experience with the standard, typical cost premiums run five to eight percent.

But the reduction in energy use provides both a direct cost payback that is guaranteed to sweeten as energy prices inevitably rise, and a public benefit payback from a reduction of the myriad externalized costs associated with energy consumption. And then there’s the potential payback in “green jobs.” What if all those triple pane windows were manufactured locally?

Furthermore, the impact of “efficiency first” strategies like Passivhaus tend to have broad, positive repercussions across systems. For example, would there be any need for a major investment in district heating systems at Yesler Terrace if most of the buildings were designed to the Passivhaus standard? Seattle City Light gives away fluorescent light bulbs for the same underlying reason.

At this stage in the climate change/peak oil game, projects like Whitmore’s Passivhaus ought to be the norm for new construction. And to help make that happen we desperately need meaningful incentives at the local, State, and Federal levels. Preferably yesterday, please, if not sooner.

Last year I wrote that “when the Harvard Business School types start hyping the decline of the suburbs, we can be pretty sure it’s game over.” Now, almost exactly one year later, an update: When the American-dream-worshipping Wall Street Journal is forced to ask “do home builders have a future?” we can be pretty sure they don’t.

As is becoming increasingly recognized, a host of well-documented and intensifying megatrends can be expected to upend the sprawling development patterns that have shaped how we live in the United States over the past half century. And one of the major casualties will be the large-lot single family home on the urban fringe. Mark Zandi, an economist with Moody’s Analytics, sums it up well in this Urban Land piece: “I can see a shift to multifamily housing and rental units. The [single-family] home ownership goal was laudable for about 25 years after the Depression, but now circumstances are different.”

The key paradigm shifts driving the coming transformation include:

- An existing supply of large single family houses sufficient to meet demand for that product for the next 20 to 30 years

- Rapidly evolving household types and sizes: empty nesters are seeking smaller housing, while at the same time, extended family arrangements are reducing demand for new housing

- A growing share of retiring Boomers, Gen Y, and to some extent Gen X that prefers low-maintenance housing in walkable, mixed-use environments

- Increasing awareness of the public health consequences of living a sedentary, auto-dependent lifestyle

- Rising gasoline prices and their effect on the cost of everything from commuting to building materials

- The restructuring of Fannie and Freddie that is likely to significantly reduce their ability to lend

- Possible elimination of mortgage interest tax deduction if the nation gets serious about deficit reduction

(A good source for details on these trends is the work University of Utah professor Arthur C. Nelson, e.g. this presentation.)

>>>

In Seattle, perhaps as much as anywhere else in the nation, the scenario is already beginning to play out. Currently in the Capitol Hill area alone, construction has just begun on eight apartment projects, and several more are beginning to stir. While most other real estate sectors are languishing, in Belltown ground was recently broken on a 654-unit market-rate apartment that, in terms of the number of residential units, will be the second largest in the city of Seattle (Harbor Steps has 730), and at 735 units per acre, reportedly will also be the State’s highest density residential building.

Meanwhile, developers that have traditionally focused on suburban single-family are busting moves into urban multifamily, as in the case of Pine Forest Properties, currently developing a six-story, 150-unit, mixed-use apartment in downtown Redmond.

Fortuitously, if the market can respond to the growing demand for urban living it’s a win-win for people and for the environment. And the first thing we need to do is simply get out of the way. That means doing away with public policy that impedes the desired transformation of the built environment, as well as preventing powerful status-quo private interests from trying to stave off the inevitable.

The second most important action we can take is to invest in infrastructure that supports transportation modes compatible with urban living, that is, transit, biking, and walking. In short, anything but more roads.

The longer we wait to acknowledge that it’s time to let sprawl rest in peace, the more grief we all will feel.

Separating the Wheat from the Chaff: Factors Affecting the Built Environment After the End of “Easy Creditâ€

Note: This article originally appeared in the Spring 2011 edition of Forum, a publication of AIA Seattle, one of the largest urban components of the American Institute of Architecture.

< Seattle; photos by Rodney Harrison >

The relative lull in development activity after the bursting of the real estate bubble has given us a chance to re-examine how changes in the economic climate may present opportunities to reshape cities.

Changes in the built environment are the physical expression of a complex web of factors that include demographics, politics, technology, and finance, among others. Even in our rapidly changing, technologically-driven world, most of the trends driving changes to the built environment have been developing for decades: increasing corporate globalization, increasing education and wealth in developing nations, increased use of technology to replace labor, an aging population in developed nations, and increasing demand for natural resources worldwide.

Some of these factors (though not all) have helped the U.S. economy grow over the past several decades. More recently, the unprecedented expansion of public and private debt—using the promise of future growth to pay for today’s needs—has masked the underlying, fundamental health of our nation’s economy. The end of the era of “easy credit,†a key enabler of real estate development of all kinds, should reveal many of the underlying trends that have been present, if somewhat obscured, during the past decades.

This downturn is not a typical recession, and as such, the path of recovery will be different than those of other recessions the U.S. has experienced. All recent recessions in this country have followed a cycle of business expansion, where typically the supply of goods rises to exceed demand, resulting in a recession as production slows, until eventually inventories of goods are consumed to the point where growth must once again resume.

The current downturn, somewhat inadequately termed the “Great Recession,†is not a cyclical business-inventory driven event, but instead was caused by a massive overhang of unserviceable debt built up over many years. The real estate bubble was the most widely visible expression of this excess.

When presented with a crisis that could lay the groundwork for fixing some of the fundamental problems impeding our economy over the past decades—including the mismatch in skills between workforce and jobs in this global economy, a transportation system ill-prepared for 21st century resource constraints, and reliance on consumer spending over industrial production for resource growth—government has instead decided to treat the symptoms as the problem.

The interventions being executed by the Federal Government could be termed the “bailout, stimulate, and print†plan. The “plan†basically entails supporting the financial system by transferring risks from private interests to the federal government, using federal spending to drive economic expansion, and inflating away the tremendous amount of public and private debt remaining from the recent bubble. In other words, growth of short-term GDP and preservation of a toxic financial system were placed ahead of real reforms that could have placed our nation on a better footing for the future.

The good news could be considered addition by subtraction. During a time of unprecedented financial constraint at the state and local level, and increasing pressure to slow the growth of federal debt, any public spending will need to be purposeful. Conservation will become a favored tactic. A massive misallocation of resources, such as the one that drove excess tract housing, strip malls, and vacation homes, is much easier when few restraints exist to building roads that perpetuate that paradigm.

< Seattle; photos by Rodney Harrison >

Key economic trends, thanks to the downturn

The downturn has produced several key economic trends that will affect our ability to change the built environment in response to underlying demographic and environmental changes.

1. Frugality will necessitate “Least Cost†alternatives, namely retrofits, re-use and conservation.

One of the outcomes of the long boom (1981 to 2001) and housing bubble (2003-2007) was the creation of real estate product not well suited by location or configuration to the demands of household size, environmental conditions, or transportation realities. Despite their sub-optimal locations, many housing units, shopping malls, and office parks could, in theory, be retrofitted for better environmental performance if certain sacrifices in mobility are made. Advances in technology should continue to make communications cheaper and reduce the need for travel, which could become more expensive as oil production diminishes. Taxes will increasingly attempt to capture the externalities of resource consumption. These factors could support rehabilitation of existing structures, both for energy efficiency and adaptive reuse.

2. Federal fiscal and regulatory policies will be imperative in shaping built environments