< Panorama of 901 5th Ave, built in 1974 >

When you look at a building built downtown in the past half century and compare it to an old building, the largest change you’ll notice other than the materials used is how they fill up space. Older buildings often are built from the sidewalk to the alley, from one property line to the other. Yet newer buildings generally take up a small amount of land and are surrounded by plazas. The reason for this was the introduction of Floor Area Ratios (FAR) in our building and land use codes.

FAR is simply the ratio of floor area to the area of the property. A 2-story building built out to the property lines would have a FAR of 2, as would a 4-story building built on half of the property or an 8-story building built on a quarter of the property. The theory behind limiting FARs is that a city can keep a large amount of open space (limiting height, width, and/or depth of a building) while allowing an architect some freedom to design their building as they’d like. The reason that open space is valued in a place like downtown Seattle is to let in sunlight, and to give developers an incentive to give future employees room to enjoy this sunlight on their lunch breaks.

I’d argue that unplanned open space has little use in a city. Parks and retail-lined plazas can be valuable in small quantity, but the landscaped or empty plazas that restricted FARs tend to leave us with are uninviting. Setbacks planned using sun angles can provide as much sunlight as our skinny towers, but with much greater density.

< The Colman Building, built in 1889 >

Of course much of Seattle might value this unplanned open space more than I do, so I propose we start small. Just as Seattle has an unlimited height zone, I propose we create an unlimited FAR zone. This zone would allow buildings built right to the property lines up to 7 stories high, then set back based on solar modeling. Buildings on an east or west side of a street might be set back more, whereas maybe a north-side building face could rise straight up. Parks and plazas would be city-planned and paid for by new construction.

The result could build a far more dense area than just increasing building heights. This density would bring everything closer – more people could access these parks, more stores and restaurants would be in walking distance, and better transit could be built. Some of our most beautiful and valued buildings and neighborhoods were built before FARs were a requirement. I’d love to see us try to build this way again.

>>>

Matt Gangemi, PE, is a mechanical engineer, and for the last decade has been designing and analyzing efficient mechanical systems for buildings. Photos by the author.

This post originally appeared on the Seattle Transit Blog.

We created Popularise—the online crowdsourcing website that provides a platform for real estate developers and public agencies to source ideas for new development projects—to empower communities and provide them with an outlet to express what they want to see local real estate projects become.  And as we began to develop the platform, we wondered if the real estate development industry would embrace it? The idea behind Popularise ran completely counter to industry norms because in the real estate development industry it is customary to share as little information as possible with the public, let alone to ask the local community to get involved.

We rolled out Popularise in December 2011 and currently have 12 buildings and projects up on our site, two of which are based in Seattle. It has been very gratifying to watch progressive developers and cities embrace this new collaborative approach to neighborhood development, and nowhere more so than in Seattle.

The first large company to approach us about using Popularise was Skanska USA who wanted to seek the input of residents, future customers, and workers near one of their Seattle developments. And they didn’t start small. At 400 Fairview, in South Lake Union, they have proposed a 350,000 square-foot, mixed-use project, where they envision a first floor market similar to Chelsea Market in New York and the Ferry Building in San Francisco.

Then the Magnuson Park Advisory Committee approached us about using Popularise to seek renovation ideas for Building 18 (The Old Firehouse). The building was submitted by Julianna Ross, chair of the Magnuson Park Advisory Committee, in an effort to save the building from the Park’s demolition list.

I may be stating the obvious, but it seems Seattle residents adopt new technologies quickly. In both instances, the two projects have seen thousands of people submit, view and support ideas on Popularise. On Friday, Fast Company wrote an article about how Skanska is adopting a new way to develop local real estate in partnership with communities—a nice validation for a company who took a risk opening themselves up to the public. Also, last Monday the Mayor of Seattle announced that he was taking Building 18 off the demolition list and is allocating $1 million in the upcoming budget to restore the building.

In both cases, we see inclusive, broad-based approaches to community engagement as a catalyst for making good things happen. My personal view is that the key is sharing power and providing a tool for transparency. Most people want to drive progressive growth but have limited opportunities to affect their environment, so when a developer or public agency asks for input and help, residents are excited to participate constructively.

Unfortunately, I don’t live in Seattle but I would love to hear what you think. Why has crowdsourcing local real estate development worked so well in Seattle? Do you have suggestions for what we should do next in the Emerald City?

>>>

Ben Miller is co-founder of Popularise, and also co-founder of Fundrise, which was discussed in this recent Citytank post.

Note:Â This post originally appeared on Alex Steffen’s blog.Â

>>>

“Strategic urbanism†is a concept I’ve been thinking a lot about lately. It was brought to mind again by Adam Greenfield’s extremely interesting notes on Ed Glaser’s Triumph of the City.

In North America, in the broadest of strokes, we might classify our approaches to the challenges of urban growth over the last four decades as laissez-faire development, NIMBY opposition to change and tactical urbanism.

Most development is still essentially laissez-faire: developers with enough money can more or less build what they want. Sure, most places have some form of zoning and most state/provincial and local governments attempt to steer development to at least some degree through provision of infrastructure and tax policies. Increasingly, many places even have some degree of formal neighborhood/urban planning. But, in general, these efforts tend to just carve some rough boundaries around what developers can build.

Mostly, the reaction to this has been NIMBYism: attempts (seen in their best light) by local residents to oppose developments they think will cost the community more than they’ll benefit it. In practice, though, NIMBYism has devolved into knee-jerk opposition to change, and efforts by small factions with narrow interests to block any new developments by jamming the public process, using frivolous lawsuits, filing environmental challenges and so on. It’s rarely the case that NIMBYs represent the wider public interest (in far too many cases, the opponents of new developments’ concerns essentially boil down to a desire to keep parking easy to find, a demand that their property values should trump all other concerns and/or a fear that more affordable housing will bring in “undesirable elementsâ€). Worse, even when their attempts to block some new project are truly genuine and reflect a desire to preserve some community value, mere opposition to change is never effective. That’s because in any city that’s not actively declining, the forces of change are inexorable. Population growth, the renewed preference for walkable urbanism, cohort replacement, gentrification, energy and climate problems, the logic of real estate investors… all these things mean that desirable urban neighborhoods will not stay the same no matter what anyone does. In reality, choosing “no change†almost always just means less change guided by the public realm and planning, and more pushed by the sheer force of money.

Tactical urbanism is something I find totally cool. It might best be summed up as investing effort in small, readily achievable projects that have the effect of altering their immediate surroundings in ways that promote good urbanism. We might think of tactical urbanism as “street hacks.†Such hacks include everything from food carts to parklets to guerrilla bike lanes. (You can look at lots of good examples in this free book.) I’m a fan, and think smart cities should be hotbeds of tactical urban innovation.

The problem is, that I think the rise of tactical urbanism actually reflects the paralysis of city-wide and systems-focused efforts. People stripe bike lanes at night at least in part because the city isn’t doing enough, fast enough, to make shared streets safer for bicyclists. People launch pop-up stores in part because the process of launching a new retail store or restaurant has become so time- and capital-consuming. People “chair-bomb†in part because so few genuinely inviting new public spaces are being built. And young people especially are trying so many new living arrangements because it’s too damn expensive to live in cities that are building effectively no new housing (in a city of a million people, growing rapidly — and subject to the pressures of smaller household sizes, gentrification and a newly resurgent urban housing market — a few hundred or even a few thousand new units a year makes essentially no difference). Tactical urbanism is cool; but the enthusiasm with which we’ve all embraced it is a tell for what we don’t talk about, which is fundamentally broken city governance.

A caveat is that in some cities, good planning has advanced despite opposition from some business interests and NIMBYs alike. But, still, only in a handful of them have the actual on-the-ground changes been large enough to achieve the sort of impacts that could produce changed systems. Though some of the success stories are startling, most of the time, North American planning is incrementalist in nature, given little actual power and small budgets, left with broken processes elected officials are fearful to reform and able to employ only a limited selection of tools to encourage positive moves. No universal law mandates that this be so.

The opposite of all this would be strategic urbanism. I’m not sure yet what strategic urbanism would actually look like, but it would certainly start from the presumption that good cities can’t thrive with broken governance, and that aggressively choosing good changes is the only path that will work. It would have to add the magnitude of density and new infrastructure that affordability, better-functioning systems, social justice and sustainability demand, while deciding to effectively preserve the qualities of places we most value.

Imagine your city actually met its needs for housing affordability, quality of life, service provision, auto-dependence, climate emissions and economic prosperity: what would it need to have done?

This might require both much more proactive encouragement of the kinds of development, commercial investment and design we want, and mechanisms for actively preserving the things about our cities we don’t want to lose. It might demand a different local politics, one based on making hard choices to shape change, rather than ineffective opposition to change or simple money-driven decision making. It might take governance as interested in economic development, capacity-building, the adaptive health of community institutions and a vibrant debate as in the classic planning silos of land use, transportation and utilities. It might demand a city whose citizens had chosen a strategy with the acumen, power and heart to to actually win the future they want, instead of simply trying to stave off the worst case scenarios they fear.

I’ll come back to this topic when I have more time. But strategic urbanism does seem to me a useful frame…

>>>

Alex Steffen is one of the world’s leading voices on sustainability, social innovation and planetary futurism. You can follow Alex on Twitter at @AlexSteffen.

< Potential loss of the building that houses the Capitol Hill icon Bauhaus Books and Coffee raised the issue of local control over real estate development >

Real estate development is essentially a math problem. How a development looks and functions is conditioned by the limits of engineering and zoning, financing, and what revenue can be generated when construction is finished. Rents, for example, are set by what people are likely to pay and how much money needs to be generated each month to cover debt service. Like any other business, real estate development can be a risky proposition with marginal profits. Generating the capital for new projects is usually a challenge, especially for innovative projects. In the end, all the numbers have to add up so that costs are covered by revenue.

What if everyone could participate in the real estate development game? What if the overall financing of a project depended significantly on money raised from people most interested in what the building looks like and how it functions because they live near by? What if building new projects, and the risks associated with them, were shared by private developers and people in the community?

It isn’t a far-fetched idea. Years ago I discovered the Ethical Property Company, a venture based in London that generates capital from private individuals in small increments as investments in acquisition, renovation, or redevelopment of real estate. How effective has it been? Here’s a summary from a recent annual report:

The Ethical Property Company owns and operates 15 centres across the UK, providing 15,000 sq m/161,000 sq ft of rentable office, event and retail space to charities, social enterprises, voluntary and campaign groups. We also provide management services to other like-minded landlords and are currently responsible for the operation of an additional six centres across the country. In total, we support over 230 organisations as tenants while over the last year an additional 460 organisations have taken advantage of the meeting and conference space within the centres we manage.

I know, I know, it’s another country and they spell funny and all that. But the idea is one that really makes a lot of sense. Why hasn’t it happened in the United States? Well, someone is trying.

Fundrise is a new Washington D.C.-based venture that is trying to create what amounts to a small-scale Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) in which investors can put money into a real estate project and reap some of the financial benefits from success. A typical REIT is gigantic, with hundreds of millions of dollars in real estate equity not to mention, sometimes, millions of square feet of land or space. Plum Creek timber is a REIT and so is Shurgard Storage.

Fundrise is a rather modest venture by comparison, and is an LLC, not a REIT. They’ve raised $203,500 from 121 investors (who have to be from Virginia or DC) with a goal of raising $325,000. The investors will own about 28 percent of the project with the rest being held by a private LLC. That means that the project costs are in the $1 million area.

A lot of people would scoff at $325,000. “Not a lot of money,†they’d say, “for a large project.†And it is true that there would be a lot of overhead to manage the contributions, thank investors, deal with the Securities and Exchange Commission and figure out payments to hundreds of small-bore investors. It’s an important start to prove that it can be done.

Community investment in real estate is an idea that I proposed earlier this year when there was a big dust-up over the possibility that Capitol Hill icon Bauhaus Books and Coffee would be a casualty of mixed use development. The Bauhaus panic inspired a wave of hyperbole from Capitol Hill Seattle Blog, which blustered about the coming of Eastside developers and the end of life as we know it on Capitol Hill.

We should put that energy into building a financing vehicle to share some of the risks and benefits with developers. Instead of cursing the private sector and real estate market we should use it to benefit a broader span of the local economy and give everyone—not just single-family homeowners—the chance to cash in as growth increases property values over time.

>>>

Roger Valdez is a Seattle researcher and writer. He read through Seattle’s land use code and blogged about it. He currently directs housing programs at a local non-profit.

Transit + Food = Sustainability in Philadelphia

(Editor’s Note:Â This post originally appeared on the VIA Architecture blog, and exemplifies how transit agencies can do a lot more than lay the tracks and build the stations.)

>>>

Like many transit agencies, Philadelphia’s SEPTA has adopted ambitious goals for sustainability performance. However, unlike most other agency plans, SEPTA’s “Septainability — Going beyond Green†sustainability program has established a specific goal to improve access to local food via transit, supported by the following initiatives:

- Identifying and studying Philadelphia’s food deserts and their access to transit, with a goal of having fresh food available within a 10-minute walk of 75 percent of Philadelphia’s population

- Partnering with local groups such as The Food Trust, The Enterprise Center, Farm-to-City, and  The Common Market to create farmer’s markets at four SEPTA rapid transit stations throughout the city

- Creating a “Farm-to-SEPTA†Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program for its own employees, where fresh produce is delivered directly to the agency headquarters

< Walnut Hill Community Farm with 46th St Station in the background; photo: Philadelphia LISC >

The fourth and most interesting initiative is the Walnut Hill Community Farm on SEPTA property, adjacent to the 46th Street Station on the Market Frankfurt light rail line in West Philadelphia. SEPTA’s project partner is The Enterprise Center, a community organization that provides access to capital, building capacity, business education and economic development opportunities for high-potential minority entrepreneurs. SEPTA provided the group with a 10-year lease and options for up to 20 years to use a 1/4-acre parcel that previously served as a staging area for station construction.

The property is divided roughly in half, with the south devoted to vegetable beds and the north to a vegetable stand and space for a future city parklet. Rainwater is collected off the 46th Street Station roof and is stored in two 1100-gallon cisterns, with irrigation pumps powered by a small photovoltaic panel mounted to the station wall. Vegetables grown on the property are sold at the Friday farmer’s market on site, and also contribute to a 65-member CSA that is augmented by produce grown on other properties inside and outside the city limits.

< Walnut Hill Farm cisterns collect water from the station roof; photo: VIA >

Since the farm opened two years ago, understanding of the complexity in promoting healthful food choices has evolved. Improvements in access to healthy food do not necessarily lead to healthy choices, and it has become clear that other factors are also important, such as budgeting, planning, and food preparation. To help close these gaps, the Enterprise Center is building a Culinary School nearby, which will provide meal planning and cooking classes designed to suit neighborhood cultural food preferences.

< Walnut Hill Community Farm; photo: VIA >

The Walnut Hill Farm provides multiple benefits to the community, including access to fresh food, maintenance of green space, pride of place resulting in less graffiti and vandalism, educational and employment opportunities for youth, and overall capacity-building within the neighborhood. For SEPTA, the farm is an opportunity to broaden its sustainability goals, create good will for the agency, and establish partnerships with a variety of groups including Drexel University, the US Department of Agriculture, the Delaware Valley Regional Food Systems Committee, the City of Philadelphia’s Get Healthy program, and the Kellogg Foundation. The connection between food and transit may not seem obvious at first, but SEPTA has provided an excellent example of how mobility and food access can be complementary ingredients of sustainable urban livability.

>>>

Catherine Calvert is Director of Community Sustainability at VIA Architecture

Helping to keep the “gross” in gross national product, at least the name Fatburger doesn’t try to hide how it feeds our vicious cycle of bloating GNP, as handily illustrated on the above marquee at the corner of SR-99 and Enchanted Parkway in Federal Way. Too many Fatburgers making you fat? No worries, just swipe the card for a membership next door at LA Fitness and—ka-ching!—GNP gets a double shot. Enchanted!

GNP went up when we built those oceans of strip malls and the 6-lane roads that feed them, and GNP went up because people needed to buy more cars and gasoline to access these places, and GNP went up because people had to work more to pay for those cars, and GNP went up because people work so much that they don’t have time to prepare healthy food at home so they hit the Fatburger, and GNP went up because frazzled, dual-income parents feel the need to outsource their kids’ play to outfits like Trampoline Nation, and GNP went up because since we drive everywhere and spend our days sitting in offices staring at computer screens we become out of shape and pay to join the gym (and drive to get there), and GNP went up because so many people don’t follow through on the fitness plan and develop obesity-related health conditions that require expensive treatment. Too bad Federal Way Crossings doesn’t also include a home security company that adds to GNP because soulless, car-dependent environments tend to fray community connections, so people turn to alarm systems to make up for not knowing their neighbors.

But nothing will get better until GNP goes up again, right?

>>>

P.S. Check out Bill McKibben’s Deep Economy for an inspiring discussion of how we could correct the perversities of our GNP obsession by restructuring economies to function more on the local scale.

>>>

Photo by the author — click to enlarge. This post is part of a series.

If you ever happen to be walking along the nearly block-long, puke-tan blank wall of the Sheraton Seattle Hotel on 7th Ave between Union and Pike and find yourself wondering what a civilized urban street facade should look like, I’ve got exciting news for you: All you have to do is look in the mirror. Because apparently some diligent designer types working for the Sheraton thought they’d jazz up their sad, dead street wall by placing a series of giant mirrors on it:

What you can see in the mirror across the street is the 1925 Eagles Auditorium Building. Good urbanism, no design regulations necessary:

The Sheraton tried to make up for their insult to the pedestrian environment that the City will be putting up with for decades by providing overhead weather protection, special paving on the sidewalk, attractive landscaping, and hmm, I guess they were thinking people might enjoy squatting on those narrow concrete stub walls to admire themselves in the mirror?

But no amount of lipstick can make up for how this side of the block lacks what matters most for a good urban street, and that’s activation, transparency, and porosity. Ah shux, well, maybe we’ll get another shot at it in half a century or so. Hopefully by then we’ll have rediscovered the sense of community that once inspired people to create humanistic urban buildings without being regulated to do so.

>>>

All photos by the author — click ’em to enlarge. This post is part of a series.

Note: Test-driving a new series—TANKSHOTS—big on images, small on words…

In typical American consumerist cities, a big thing like a sofa can often become more of a liability than an asset. We move a lot; we buy too much stuff; the stuff we buy is not built to last; space to keep our stuff is becoming more constrained as the city densifies.

And so the value of that plush matched sofa set becomes zero—not even worth the hassle of selling on Craigslist. All the more ludicrous when you consider the global financial, manufacturing, and transportation networks necessary to put those pieces of furniture on the showroom floor.

The $35k car in the photo will also become a liability before too long. But directly behind that empty lot on MLK Way in the Central District is the city’s first LEED-certified townhouse project, which is shooting for at least a 30 percent reduction in energy use compared to the current norm—in other words, it will be an asset with increasing value over time as energy costs inevitably rise.

One of the many potential payoffs from the renewed attraction to city living in places like Seattle is that it should help cure us of our addiction to stuff, so that we can invest more in true assets.

>>>

Photo by the author—click to enlarge.

Seattle’s Living Building Pilot Program: A Case Study in Progressive Divisiveness

The first question to ask about the current debate over Seattle’s Living Building Pilot Program is, why is there a debate at all? It’s just plain embarrassing that in a City that talks so loud and proud about sustainability, once again we have such hand wringing over a modest piece of legislation that is so obviously the right thing to do.

Launched in December 2009, the Living Building Pilot Program (LBPP) is designed to incentivize the development of buildings that operate on one quarter of the energy and water consumed by a typical building. If a new building can achieve those highly demanding specs, and also capture and use half of the rainwater that hits its site, and also meet 60 percent of the “imperatives” of the rigorous Living Building Challenge, then it becomes eligible for a range of departures from standard code requirements, subject to City approval. Departures are offered as a way to enable innovative design solutions and help compensate for the added costs associated with meeting the stringent performance targets.

The value of the long-term public benefit derived from buildings that qualify for the LBPP cannot be understated, particularly regarding energy. We all know about climate change and the harsh realities of an increasingly resource-constrained planet, right? Achieving anything even close to carbon neutrality in Seattle is going to require huge reductions in building energy use, and we need to get on it now because new buildings will be on the ground for decades.

This year some changes to the LBPP were proposed, based in part on the real-world experience of the second development project attempting to qualify—the “Stone34” office building in the Wallingford neighborhood (the first project was the Bullitt Center, pictured above). The key proposed updates are the exemption of ground-floor retail space from floor-area-ratio limits, and an increase of the height bonus from 10 to 20 feet in certain commercial zones.

And of course it’s the building height that has become the lightning rod for opposition, the typical hyperventilating well illustrated in this flyer thick with blatantly misleading claims. Though Matthew Yglesias wrote from a national perspective in the following, one could easily assume that Seattle was his muse:

When progressives see a fight pitting a neighborhood activist against rich developers, their instinct is to side with the activist, even if all the developer really wants to do is erect a building that will allow a lot more people to live or work or shop in their neighborhood. Indeed, the vast majority of big city residents are deeply committed to liberal politics on the national level, but feel just as comfortable standing with entrenched interests seeking to block change on a local level.

What’s doubly remarkable is that even with all the truly great features of the Stone34 project—vastly reduced resource consumption, high-quality design and materials, generous public open space, sprawl-reducing location, economic development—the above mindset is still operative.

Another disappointing twist in the current debate is push back from the International Living Future Institute, creators of the Living Building Challenge, who are concerned about the proposed updates essentially because they want to protect their brand—it’s easier to qualify for the City’s Living Building Pilot Program than for full-on, official Living Building certification. Fair enough, but how sad to see an organization whose mission is to advance green building criticizing legislation that would help enable the second greenest office building ever built in Seattle. The simple resolution would be to rename the program, but that would set the legislative process back months. So would it really be that hard for the City and the Living Future folks to play nice and come to an agreement on renaming the program as soon as possible?

Clearly the progressive community has a masochistic fetish for divisive bickering, a fetish in which Seattle indulges perhaps more than any other U.S. city. So the circus of angst that typically erupts around what ought to be no-brainer sustainability policy decisions shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone, though that doesn’t make it any less counterproductive (or irritating).

The first part of the solution is for Seattle’s elected officials to accept that they have a responsibility to make policy based on objective reality no matter how many deluded naysayers may try to deny that reality, and that there are times when they need to stop wasting everyone’s time with endless debate and do their jobs as leaders and decision makers. It’s perfectly okay—a good thing, actually—for Councilmembers to ignore progressives who habitually talk smack, or in the case at hand, those who howl about “monster buildings in my backyard,” or grouse that policy promoting a building that reduces energy use by 75 percent is just a greenwashed developer giveaway.

The second part of the solution involves healing the dysfunctional schism within the progressive community over sustainable development and land use policy. No small task, that. We are tangling with human nature—people who like the way things are resist change, and nobody wants “outsiders” controlling their destiny. At the same time, those who believe massive change is imperative must be careful not to lose touch with the concerns of people who may be directly impacted (yes, I am guilty).

We progressives agree on pretty much every other issue. Surely we can find a way to come out of our corners, find common cause, and collaboratively take on the fuck-ton of work there is to do on creating a city equipped to thrive in the coming decades.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is a Seattle resident and the creator of Citytank.

Dispatch from the SPC: Finding affordable, family-size housing: S.O.L. in Seattle?

Note: This post is part of an ongoing series of dispatches from the Seattle Planning Commission.

>>>

Riffing on movie titles makes for catchy blog headlines. But are families in search of housing they can afford really S.O.L in Seattle? The answer is often yes, especially for low- and middle-income families with more than three people. In fact, some of the most concerning statistics from the Planning Commission’s Housing Seattle report relate to the supply of affordable family-size housing.

- A scant 5 percent of the family-size homes sold in 2009 were affordable to families with a low income and only about 30 percent were within the reach of middle-income families. (And these stats include sales of townhomes and condos, not just single-family detached homes!)

- Just 2 percent of market-rate apartment units in Seattle even have three or more bedrooms, and only half of this tiny fraction are affordable to low-income families.

Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan says that we want a mix of housing that’s attractive and affordable to households of a variety of types, sizes, and income levels. Housing a greater share of King County’s families with children is an explicit goal in the Plan.

These goals are going to be tough to achieve without more affordable, family-sized units. They’ll be doubly difficult if family-sized units are left out of the denser housing mix that’s going to make up most of the city’s growth.

Including larger units in the mix isn’t only about housing for families with children under 18. It’s also about housing for multi-generational households, including families with adult children working to (re)gain their economic footing, couples with elderly parents, and families whose traditions include three generations living together. These are growing demographic segments both nationally and in our own region.

Seattle has limited tools available to influence the housing market supply. Still, we need to get more creative to ensure that we are doing what we can.

- One specific Commission recommendation is to revise existing incentive programs for developing affordable housing to prioritize the creation of family-size units. These enhanced incentives could be applied citywide or in particular locations such as near schools and in transit communities.

- The City also needs to update policies and codes to encourage greater concentrations of family-friendly multifamily housing near schools and parks, especially in urban centers, villages, and transit communities. There’s no better time to do this than now, when a major update of the Comprehensive Plan is underway!

Of course this isn’t only a housing issue. To attract and support families, neighborhoods need high quality schools and outdoor spaces for play, and neighborhoods need to be safe. To create the critical mass of conditions required, the City and its public and private partners in the community need to work together on multiple fronts to make sure that rather than SOL, families live (and of course sleep) happily in Seattle.

>>>

The percentage of households made up of families with children is lower in Seattle than in every other major city in the U.S. except San Francisco. On a brighter note, the number of families with children in Seattle rose by more than 4,500 between the years 2000 and 2010.

The percentage of households made up of families with children is lower in Seattle than in every other major city in the U.S. except San Francisco. On a brighter note, the number of families with children in Seattle rose by more than 4,500 between the years 2000 and 2010.

Â

Â

Â

Â

>>>

Diana Canzoneri is the staff Demographer for the Seattle Planning Commission and was the primary researcher and analyst for the Commission Housing Seattle report. She analyzes census and market data and provides demographic analysis related to comprehensive planning, community development and long-range planning for the Commission as well as City officials and departments.

Dispatch from the SPC: Life Along the Fast Lanes

Note: This post is part of an ongoing series of dispatches from the Seattle Planning Commission.

>>>

In our Dispatch posted on May 15, 2012, Affordable Living: What’s transportation got to do with it?, we highlighted an important point from our recently released Housing Seattle report: mobility options and close proximity to jobs and activities may help offset higher housing costs. Lower-income households, especially, can gain the most from the livability benefits and transportation cost-savings possible in a transit community. Improving access to affordable transportation and developing a citywide Transit Communities policy that includes an aggressive housing affordability component are important steps toward making living in Seattle affordable to a greater number of people.

< Photo courtesy of America Walks >

Our report also found that the lion’s share of Seattle’s affordable market-rate units are located on or near arterials. The good news is that even outside of transit communities, many of Seattle’s arterials are served by at least one transit route providing frequent service. Yet, arterials often have big quality-of-life negatives for the individuals and families who live next to them (as well as for the transit commuters who traverse and wait along them). Depending on their design, arterials can be downright dangerous for people to walk along or cross. Fast driving speeds, high traffic volumes, long intervals between signalized crossings, wide roadways, and inadequate sidewalks contribute to risks beyond the general unpleasantness associated with traveling in these areas. Conditions along arterial corridors are especially perilous for children and the elderly.

As a city, we can’t lose sight of the need to reduce the risks to life itself along the city’s long arterial stretches where many of Seattle’s young families and low-income households now live. Streets of all types are vital public spaces in our neighborhoods, and we need to invest to make them multifunctional, safe, and inviting.

< Greenlake area townhouse owners Joshua Hockett and Michelle Zeidman support efforts to calm and slow down cars in their neighborhood. Click image to read more about their spotlight story. >

Seattle’s Pedestrian Master Plan specifies priority locations for improvements (along and across) roadways. Awe-inspiringly extensive analysis went into identifying these priority locations based on 1) where people most need to walk and 2) where opportunities for improvement are greatest. Many of these are locations on Seattle’s major arterials where ped-safety upgrades are badly needed.

By design or default, our arterial corridors will continue to play an important role in providing the combination of affordable housing and transit that many households require in order to live in Seattle. As we create our terrific transit communities, let’s prioritize ped-safety improvements with an eye towards equity.

Diana Canzoneri is the staff Demographer for the Seattle Planning Commission and was the primary researcher and analyst for the Commission Housing Seattle report. She analyzes census and market data and provides demographic analysis related to comprehensive planning, community development and long-range planning for the Commission as well as City officials and departments.

Diana Canzoneri is the staff Demographer for the Seattle Planning Commission and was the primary researcher and analyst for the Commission Housing Seattle report. She analyzes census and market data and provides demographic analysis related to comprehensive planning, community development and long-range planning for the Commission as well as City officials and departments.

Last month, we took a street for an evening. We acquired no permits, held no visioning meetings, received no funding. We took an unloved, underutilized piece of public right-of-way and transformed it into a place of potential, a pocket of social interaction. Maybe a touch grandiose, sure, but we did temporarily add life to a street in a way that’s not normally allowed.

This intervention was grounded in three findings:

- Cities are broke – Budgets are contracting and we have to reconceive our expectations of what the city can/should provide for the public realm.

- Streets are underutilized – 33% of Seattle is in the public right-of-way. Streets like the Summit stub (see photo above) have a capacity of 2000 cars/hr, yet are used by less than 100 cars/hr.** When land is underused and redundant (especially public land), we should look for better uses of that land.

- Our space and time are precious – The land underneath the Summit Stub is worth about $500,000.*** Is that really the best investment of our limited resources and space? Should we have to wait months or years to make it better?

So, through action, we propose a simple fix:

- Change the process: For less than the current price of permit review, we transformed the space. With communally donated parts and labor, we don’t need millions of dollars to make great urban spaces.  The city just needs to designate space and let the neighborhood do the rest.

- Change the mindset: We need to ditch the notion that the city is a fixed entity. The life of a city is dynamic and the way in which we plan for and use our public space should reflect that understanding. We need a system that allows for temporary action, for phased development, for experimentation. Maintaining the status quo may be easier and won’t upset anyone, but it’s also inefficient and inequitable. Worst of all, it’s boring.

On June 14th, we’ll be transforming the Summit stub again. As a real time case study, we’re learning about how a dead space can be converted to a living one.  Lighter, quicker, and cheaper. Show up and help shape the future of our public realm. More information at facebook.com/rpcollective.

>>>

Seth Geiser is an urban designer who clearly has some time on his hands. Kirk Hovenkotter is an urban planner working professionally at a city and likes, nay loves, transit.

* A useful phrase, cribbed from pps.org/reference/lighter-quicker-cheaper-2-2

** As observed by semi-rigorous, probably non-scientific traffic counts

***Based on a rate of $125/sqft for lots adjoining the site

For those who hope for the kind of transformational change that will be necessary to create a truly sustainable and resilient Seattle, the City’s disproportionate reaction to Mayor McGinn’s recently proposed set of regulatory reforms is a far more important issue to tackle than the reforms themselves. Consisting of relatively modest, low-hanging-fruit tweaks to the land use code intended to enhance livability and the local economy, the proposal has generated an astounding amount of opposition, most recently with a crowd of naysayers at a Council hearing that succeeded in getting one major component of the proposal thrown out.

The psychology behind this scenario is complex. The ugly legacy of urban renewal still casts its shadow, and at the core we’re dealing with a wariness of change that is basic human nature. But while this attitude can be an obstacle to progress in many U.S. cities, here in Seattle it has festered with a mix of timid political leadership and an expectation that everyone must be not only heard but appeased, to form a singularly toxic political dysfunction that would be an entertaining intellectual curiosity if it wasn’t so potentially detrimental to the future of the City.

This is not to say that Seattle is making no progress. It is. But considering all the brainpower, wealth, and environmental concern to be found among Seattleites, our eccentric political culture is the biggest impediment to public policy that would bring Seattle to the international forefront of sustainability.

The Developer Stigma

Consider McGinn’s regulatory reform proposal as illustrative example. First of all, as played up in the Seattle Times, the fact that some of the people on the advisory group have connections to the development community is apparently all we need to know in order to conclude that it’s all about lining developers’ pockets. Never mind the reality that Seattle has one of the most progressive development communities in the country. And never mind that developers know a thing or two about putting up buildings, which happen to be something that we want more of in Seattle, both to satisfy demand from people who want to live here, and to garner the local and regional benefits of smart growth. And never mind that urban infill redevelopment has the potential to be a massive economic engine that fills the gap left by the decline in construction of sprawl.

Why is this knee-jerk enmity of developers so prevalent in Seattle? Where are the existing development horror stories that people are so afraid of repeating? Sure, there are a few clunker buildings here and there, but by and large Seattle’s built environment is good and getting better. And Seattle is a city thick with corporate influence—so why do developers take so much heat for being fat cats? I see no rational answers.

What’s Not To Like?

The piece of the reform package that was shot down last week would have allowed small commercial establishments in some multifamily zones, as a strategy to help “bring back the corner store.” First of all, how, one might ask, would this benefit developer interests? It doesn’t, and in fact one could argue that it is against their interests because it would open up competition for the retail spaces that are typically part of new mixed-use projects.

There are no doubt some who fear the invasion of ludicrous commercial uses—A topless barbershop! A corner Walmart!—but these concerns are irrational and deserve to be ignored as such. Others object more judiciously to new uses that would be “out of character” with the neighborhood, that handy catch-all phrase for anything someone doesn’t particularly like.

But wait, last I checked I thought we progressive Seattleites were supposed to be all enamored with exactly the kind of small independent businesses that this policy was designed to promote. And don’t we all love the idea of the kid running to the corner store for a quart of milk? What on earth is everyone so afraid of? It’s like Seattle’s angst-ridden debate over backyard cottages all over again.

Too Much Walkability?

Some residents of Capitol Hill expressed more nuanced objections: Why allow commercial uses in more areas when there are already so many empty existing street-level retail spaces, and when many urban villages in Seattle have great walkability as is? In response to Walkscore being cited to support the latter, Walkscore’s Matt Lerner tweeted that he “never imagined a high Walkscore would be used to prevent walkability.” Furthermore, the code would apply to areas across the entire City of Seattle, which has plenty of neighborhoods that lack walkable access to stores and services.

It is true that street-level retail is less viable when spread out and diluted. However, the reason many existing spaces aren’t landing tenants is because they are too expensive, or don’t have the right spatial layout, or are poorly located. Indeed, a common complaint about new mixed-use buildings is that the retail spaces are too large and expensive for small-scale independent businesses. The proposed reform would have helped open up affordable, usable alternatives to these spaces—otherwise known as creating economic opportunity for the little guy.

In any case, as we have learned from the current glut of vacant street-level retail spaces scattered across Seattle, a flexible, market-based approach to small-scale commercial is likely to be more successful than trying to mandate where it should or shouldn’t be. After all, that’s how Seattle’s best neighborhood centers developed in the first place, organically creating the kind of practical, livable mixed-use urban form that we’re trying to emulate today.

Naysayers Win

Given how relatively benign the commercial use proposal was, it’s apparent that much of the opposition was driven by indignation over being left out of the process. Yes, Mayor McGinn deserves some blame for that, and yes, Seattle’s residents have much insight to contribute. But I have to wonder if some opponents are letting their indignation preclude a fair assessment of the issue at hand. If it’s a good idea, who cares who proposed it? Is the full-on, dragged-out Seattle process really necessary for every policy decision?

In hindsight, the smarter political approach would have been to put stricter limits on the proposal, such as a smaller allowed floor area, or an exclusion of particularly objectionable business types. This would have helped ease concerns and diffuse opposition, and there would always be the opportunity to update the code after people got more comfortable with it over time. Incremental change is better than no change.

And what of the Council’s acquiescence to the naysayers? Those who testify at Council hearings do not necessarily reflect the sentiments of the entire community—especially at hearings in the middle of the day when most people work. Nor do neighborhood group leaders necessarily speak for the majority in their neighborhoods. And on my read, the views expressed by Capitol Hill residents who were agitated enough to show up at last week’s hearing are not shared by most people who live in “vibrant, walkable urban centers,” in contrast to what Councilmembers apparently assumed.

The fact that a few dozen motivated naysayers so easily swayed the Council to abruptly kill a thoughtful policy proposal a year in the making is classic Seattle-style political dysfunction. And if Seattle’s electeds continue to be incapable of providing consolidated leadership in the face of opposition to relatively painless policy changes like McGinn’s regulatory reform, we might as well forget about ambitious goals such as carbon neutrality that are guaranteed to involve far more challenging policy and politics.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is a Seattle resident and the creator of Citytank.

(P.S. The regulatory reform proposal also contains two other components—adjustment of the SEPA categorical exemption, and elimination of off-street parking requirements within a quarter mile of frequent transit—that have already generated controversy, and will no doubt stir up more as they are taken up by Council. I’m hoping that my masochistic tendencies will sufficiently motivate me to address these in followup posts.)

Get Stoked to Surf The Fourth Wave of Planning

(Note: the following was submitted but not selected for the 2012 Living Future Conference’s 15 Minutes of Brilliance.)

>>>

Last year in Seattle, the Bullitt Foundation’s proposed Living Building was subjected to a costly legal challenge based on Washington’s State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). Opponents argued that an environmental impact statement (EIS) should be required because the building would block views. Given that it’s on track to being one of the greenest commercial buildings ever constructed in the United States, and is also located in a dense, walkable, transit-rich neighborhood, the fact that environmental regulations could be exploited to oppose the project suggests something is amiss, to put it mildly.

Following on the heels of the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Washington’s SEPA was created during an era in which the planning culture was dominated by concerns over ecological degradation and responded with strict limits on growth -– planning’s so-called first wave. In the mid-1970s planning entered its second wave, focused on comprehensive planning and infrastructure, followed by a third wave defined by “smart growth†that began around the turn of the century and is still the prevailing approach today.

And now a fourth wave of planning is emerging, with a perspective that will hopefully put an end to perverse contradictions such as what happened with the Bullitt Foundation Living Building. The formative influences on planning’s fourth wave are the “new normal†economy, climate change, energy, food systems, and regional sustainable development.

< The LEED Platinum Center for Urban Waters on the Foss Waterway in Tacoma; photo by Dan Bertolet - click to enlarge >

So then, how do we make this transition to the fourth wave and a new regulatory milieu that accurately reflects the profound, inherent environmental benefits of compact, mixed-use urban infill? As one example of a modest first step, Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood is in the midst of a lengthy upzone process that required a voluminous EIS. To counter the typical “growth is bad†perspective of the EIS, I (while with my former employer, GGLO) worked with a group of local property owners to create an Environmental Benefits Statement that articulates the wide range of benefits that high-intensity redevelopment would bring.

As a second example, my firm is currently engaged in a Subarea planning process in Tacoma that will implement a brand new flavor of Upfront SEPA that was designed to encourage infill around transit. The EIS will pre-approve a set amount of development across the Subarea, and once adopted, it cannot be appealed.

But ultimately, what our environmental policy needs is a makeover. Massive change is upon us, and we can’t afford to let crusty regulations needlessly impede progress on what is already a mind-numbingly overwhelming challenge. NEPA and SEPA were created in the hey-day of muscle cars, and it’s time to sort out the pieces that belong in the policy junk yard. At the same time, new policy must be added to ensure that we properly account for expanding knowledge and game-changing trends such as global warming. All that’s stopping us from surfing the fourth wave and creating a revamped set of regulations that make sense for the 21st century, is us.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban planner with VIA Architecture and the creator of the Citytank.

Dispatch from the SPC: Affordable Living: What’s transportation got to do with it?

Note: This post is part of an ongoing series of dispatches from the Seattle Planning Commission.

>>>

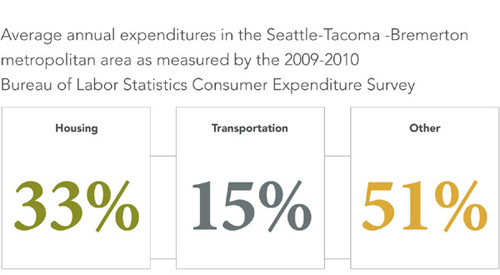

Not surprisingly, housing is the largest cost for households in the Seattle area, yet transportation also accounts for a substantial chunk of our spending. On average, about 33 percent of what we spend each year goes to housing, while another 15 percent goes to transportation. That’s close to half the amount we pay to keep a roof over our heads.

As the Planning Commission details in its recently released Housing Seattle report, the share of households with unaffordable housing costs has increased substantially since the 2000 Census. In order to reverse this trend, Seattle must advance “affordable living” on a broader level. Improving access to affordable transportation and developing a citywide Transit Communities policy are important steps toward making living in Seattle affordable to a greater number of people.

The American Public Transit Association calculates that a two-car household in Seattle can save an average of $12,000 per year if they give up one of their cars and one driver commutes via transit. That’s real money that could go toward housing costs instead.

Maps created by the Center for Neighborhood Technology show that households in locations with higher housing densities and levels of transit service tend to have lower transportation costs. Our report found that households with low incomes are under the greatest strain from both housing and transportation costs. In order to address both issues, one of the Planning Commission’s key recommendations is to build most new subsidized housing within transit communities. In a transit community, residents can easily walk, bike, or take transit to get to work, school, and more, and they don’t have to transfer twice and miss dinner with their kids to do it!

Maps created by the Center for Neighborhood Technology show that households in locations with higher housing densities and levels of transit service tend to have lower transportation costs. Our report found that households with low incomes are under the greatest strain from both housing and transportation costs. In order to address both issues, one of the Planning Commission’s key recommendations is to build most new subsidized housing within transit communities. In a transit community, residents can easily walk, bike, or take transit to get to work, school, and more, and they don’t have to transfer twice and miss dinner with their kids to do it!

Neither APTA’s nor CNT’s methodology is perfect. Still, a combination of data and personal narratives like those featured in Housing Seattle make a compelling case: transportation policies and choices have a big impact on determining who can afford to live and work in Seattle. Let’s pursue a citywide Transit Communities policy, increase access to transit and invest in our transit communities, and help keep Seattle open to all.

>>>

Diana Canzoneri is the staff Demographer for the Seattle Planning Commission and was the primary researcher and analyst for the Commission Housing Seattle report. She analyzes census and market data and provides demographic analysis related to comprehensive planning, community development and long-range planning for the Commission as well as City officials and departments.

Diana Canzoneri is the staff Demographer for the Seattle Planning Commission and was the primary researcher and analyst for the Commission Housing Seattle report. She analyzes census and market data and provides demographic analysis related to comprehensive planning, community development and long-range planning for the Commission as well as City officials and departments.

The 2012 Living Future Conference was held in the bike mecca of Portland, so how could I not bring along the Cannondale beater, which Amtrak stashed onto the baggage car for an extra five dollars. The train from Seattle to Portland is a magical ride, slicing through hidden back alleys, skirting the spectacular edge of Commencement Bay, and finally crossing the Columbia before rolling into cozy Northwest Portland. Luggage on my back, I pedaled out into the drizzly shiny night, careful to keep my tires out of the street car slots, while the quick, mellow ride to my hotel near Powell’s Books reminded me once again how amazingly comfortable and convenient downtown Portland is without a car.

Not your father’s green architecture conference, Living Future prides itself on drawing people outside of their boxes and making them uncomfortable—in a good way. Case in point, in his plenary talk, Living Future Institute CEO Jason McLennan described how twice in past years the conference organically adopted a four letter word as the conference theme, and proceeded to provoke audience members to shout them out—picture a huge conference ballroom packed with 800 people erupting with shouts of “shit!” and then “fuck!”

Not to be outdone, McLennan proposed a new four letter theme word for this year’s conference:Â love.

The essence of Living Future is regenerative design, the idea that design should develop the potential of whole systems and empower them to regenerate and evolve indefinitely. A lofty and challenging aspiration, no doubt, one that calls for nurturing intricate webs of relationships, recognizing the interdependence of all life, and eliminating our tendency to see ourselves as something separate from nature. And love is an apt choice of words to capture the core sentiment of that philosophy. It’s analogous to what wise parents know about their children: You can’t make them do what you want them to do, but you can give them everything they need to grow and realize their full, natural potential.

Places can be thought of in the same way. In Portland the exceptional energy and care that has been put into improving the public realm and promoting walking, biking and transit should help unleash the City’s potential to become a regenerative place with the capacity to evolve in powerful, unforeseen ways. It will probably be a decade or more before we know the extent to which Portland’s investments help create a more resilient, culturally and economically thriving city. But when I’m in Portland these days I love what I see so far.

Reductionist analysis has enabled spectacular human progress over the past few centuries, but has also put us on a collision course with the carrying capacity of our planet. Restoring balance calls for shifting our emphasis to relationships, patterns, and systems, a shift that would be all the more likely if we reframed our outlook through the lens of love. Not that this would be an easy task for a society with the habit of ignoring whatever doesn’t show up in the economists’ balance sheets.

Indeed, the most elevating things in life—social bonds, fulfillment, memories, dreams, dignity, devotion—cannot be accounted for in the analytical bottom line. And we’ve been so obsessed with the quantifiable for so long it’s almost impossible for most of us to imagine how these intangibles could play an influential role in the major decisions that shape our world. But we ought to start imagining it if we hope to steer our course away from the brink and toward a regenerative future.

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban planner at VIA Architecture and the creator of Citytank.

Great City Building Starts With A Back-of-the-Napkin Sketch

< Looking west from the corner of Lenora Street and Westlake Ave in downtown Seattle. The car lot on the right is the site of a future office tower for Amazon.com; photo by Dan Bertolet - click to enlarge >

Today is Earth Day, but I still think we need a City Day too, because in this era of global urbanization, what happens in cities will largely determine the fate of the Earth. And how we build our cities will dictate what happens in them.

In this spirit of progressive city building, you are invited to the second City Builder Happy Hour, Tuesday May 1, 5pm to 7pm at the Pike Brewing Company, 1415 1st Avenue in downtown Seattle (Facebook invite).

Do you have an idea for how we can build a better city? Do you want to be given the spotlight to mouth off about it during the next City Builder happy hour? If yes, please submit your idea on the back of a cocktail napkin. You can email a picture of the napkin to tanked@citytank.org, or mail it to City Builder Happy Hour, c/o Sierra Hansen, 1809 Seventh Ave, Suite 1111 Seattle, WA 98101.

At the first City Builder happy hour, Matt Roewe pitched his idea for a gondola connecting Capitol Hill to Seattle Center. Matt’s blog post on the same topic set a new record for page views on Citytank, and the story was picked up by a wide range of media including local TV news. Can you top that?

urban development as a mindfulness practice.

< Skanska's proposed Living Building in Seattle's Wallingford neighborhood; image courtesy LMN Architects - click to enlarge >

Juxtaposing urban development and mindfulness in the same sentence appears akin to throwing a reunion party for the north and south poles: a futile attempt of gathering opposites. However, the practice of mindfulness is limitless, accepting and able to party with anyone.

I am a real estate developer educated in urban planning and embedded with a civic decoder, loving to hack the physical and social patterns present around me. This is the awareness innate to passionate place makers, where I seek to belong.

I began studying awareness after several experiences pushed me to feel, and use my right brain. This level of awareness is intuitive, creative, natural and effortless. It’s void of thinking or creating logic, and it is immediately present. Neuroscientists view thinking as mental activity focused on past events or future projections (left brain). Sit still and observe over 5 minutes where your mind goes, and 99.9% of it has nothing to do with you just sitting there, feeling the moment (being in the right brain).

Clinical psychology defines mindfulness as a self-regulation of attention maintained on the immediate experience (i.e. not past or future). This attention increases recognition of the present moment and involves adopting an orientation characterized by curiosity, openness and acceptance. This is a mental state or knowing that is beyond what can be thought. Fun, eh?

A mindful awareness is the very real and present space where urban development, or place making, has authentic voice and power for me. The most valued community development is present and connected to human feeling and experience. Highly valued urban spaces are rarely a construct of past experiences or future projections (e.g. the urban simulacra of Las Vegas); rather real urban spaces are organic forms created by people working together to push aside fears, embrace uncertainty and rest in the knowing of not knowing.

Louis Sullivan’s famous aesthetic credo of form and function affirms that it is not just our heads that go to create functional urban places. He states…

“It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic,

Of all things physical and metaphysical,

Of all things human and all things super-human,

Of all true manifestations of the head,

Of the heart, of the soul,

That the life is recognizable in its expression,

That form ever follows function.â€

Therefore, when cities (form) result from unawareness or as places shaped by what we fear, our landscapes are molded into places that only breed more fear.

Seth Godin calls this fearful paradigm the “No Coalition,†where the No Coalition only requires just one objection, one defensible reason to avoid change.  And the No Coalition has many allies — anyone who fears the future or stands to benefit from the status quo (e.g. a view from a living room, availability of parking, time it takes to drive to work, etc.). Further, “No†is easy to say, because people don’t actually need a reason to say no. No instantly grabs power and slows things down because with yes comes responsibility.

Godin says, “No comes from fear and greed and, most of all, a shortage of openness and attention. You don’t have to pay attention or do the math or role play the outcomes in order to join the coalition that would rather things stay as they are (because they’ve chosen not to do the hard work of imagining how they might be).â€

Like Godin, I live in a world of yes, where possibility and innovation and the willingness to care seek to triumph over the coalition that would rather it all just quieted down and went back to normal.

How do we stop this vicious cycle of fear leading to bad form leading to more fear? Having a new civic awareness that is not based on what we fear but having responsibility for change.

To be an effective and mindful developer, my challenge is to realize that communities and stakeholders probably know something I don’t, or more likely do not see what I see. My job is to figure out what are their fears, biases and perspectives, then help them understand what I know. Ultimately we are at our best when we mutually cultivate a collective awareness together to bring about urban places that foster the health of our communities for generations to come.

Join me.

>>>

Lisa Picard has over 18 years of experience in the conceptualization, design, finance and management of large real estate projects, in various types of mixedâ€use developments valued at over $1.2 billion. Holding a master’s degree in urban planning and another in real estate finance, both from MIT, Lisa seeks to push urban development to an increased value that exceeds what is possible by pursuing the needs of a single stakeholder. Currently, Lisa is leading Skanska’s west coast development strategy with two projects currently underway in Seattle; the first project (rendered above) is participating in the City’s Living Building Pilot Program and is confronting some resistance by nearby neighbors.

What would happen if someone wanted to build a Space Needle in Seattle today?

One word: fahgettaboudit.

Today, a proposal with the audacity of the Space Needle would incite an citywide naysayer orgy. It will compete with views of the mountains! It’s a waste of money! It’s out of character with the neighborhood! Where’s the affordable housing? Not unless they also pay for a 3000 stall parking garage! It’s just plain silly and we need to get serious!

Our collective character has changed over the past half century. And my take on it is that the critical element is confidence. In the early 1960s, we had gobs of it. But since then, a series of setbacks from Vietnam to the recent banking implosions have steadily drained it. And that unconfident state of mind, perhaps more than any other factor, is the biggest threat to the success of our efforts to tackle the challenges of the future and create a world in which humanity’s journey continues to expand and thrive.

< In the late 19th Century many Parisians vehemently opposed the Eiffel Tower; image from the movie "Hugo" via bplusmovieblog.com >

Curing a lack of confidence is a quandary, because the kind of dramatic successes that inspire confidence require bold action and risk taking, precisely the type of behavior that a lack of confidence inhibits. But the first step is to at least recognize this dynamic.

As an example, consider the recently proposed idea to run a gondola from Capitol Hill to Seattle Center. While there were some who loved the idea (e.g. me), most of the responses I heard or read were not too far off from some of the objections I facetiously suggested above. It seems the serious people—the grown ups—were all too eager to dismiss the idea of a gondola as naive and out of the question.

The reality is that gondolas can be efficient and cost-effective urban transportation, and a gondola is a smart, outside-the-box solution for the unique set of obstacles associated with east-west travel in central Seattle. Gondolas have been successfully implemented in cities worldwide, one of the most impressive examples being in Medellin, Columbia, where a network of nine cable cars that primarily serves the poor was completed in 2010. But when minds are stonewalled by a lack of confidence, such positives tend to be overlooked, and instead people focus on all the reasons why it could never work.

But more importantly from the standpoint of confidence, besides being a practical transportation solution, a gondola from Capitol Hill to Seattle Center would be an outrageously cool thing. People would ride it just for the awesome views. It would become a Seattle icon that no other major U.S. city could match. It would be, dare I say, fun. And all that positive mojo would breed confidence.

The proposed gondola would require a high-rise tower at the Capitol Hill light rail station, an idea that likewise faces resistance at least in part, I believe, due to a lack of confidence and a corresponding aversion to bold thinking. On the practical side, the added value of a high-rise project could help fund the long list of public amenities that the neighborhood wants. On the inspirational side, an iconic tower on Capitol Hill could become a placemaking symbol for the next “Next 50,” those who see a bright future in urban density and transit, and who also wish to celebrate the most socially progressive city neighborhood in the Pacific Northwest.

Seattle is among the most wealthy, highly educated, and politically liberal cities in the United States. How is it that in Columbia—a country with a per capita income about one fifth of ours—they manage to build a system of nine gondolas, while we balk at the idea of even seriously considering one?

And why isn’t Seattle jumping at the chance to expand LINK light right into a city-wide subway system, as proposed by the activists of the new Seattle Subway initiative? Starting in 1991, the City of Athens, Greece, began constructing a subway that opened in 2000 and now serves 33 stations on 29 miles of track. Per capita income in Greece is roughly half that in the U.S. Not to mention the torrent of rail transit being built in China (more than 3000 miles worth in 2010 alone).

For sure, Seattle’s got a lot of great things going on, as I gushingly described recently. But that’s exactly what offers Seattle the opportunity to take it up a notch and really start pushing the envelope, not only to take on the toughest challenges like public transportation, but also to create an inspirational example of city building done with intention, passion, and soul.

The brains are here. The money is here.

Hey Seattle, got confidence?

Grading the Green City: Applying LEED-ND to the Existing Built Environment

When NRDC, the Congress for the New Urbanism, and the US Green Building Council created the LEED for Neighborhood Development rating system, their aim was to rethink how development could address climate change, sprawl, and threats to human health. The overarching LEED platform had mainstreamed green building, and LEED-ND was an effort to expand its scope beyond the building shell for a more comprehensive standard of neighborhood sustainability.

Shaping the direction of future development is crucial to promoting livable communities in an expanding world. But what if, instead of looking ahead to future development, we used the LEED-ND criteria to evaluate the sustainability of the existing built environment?

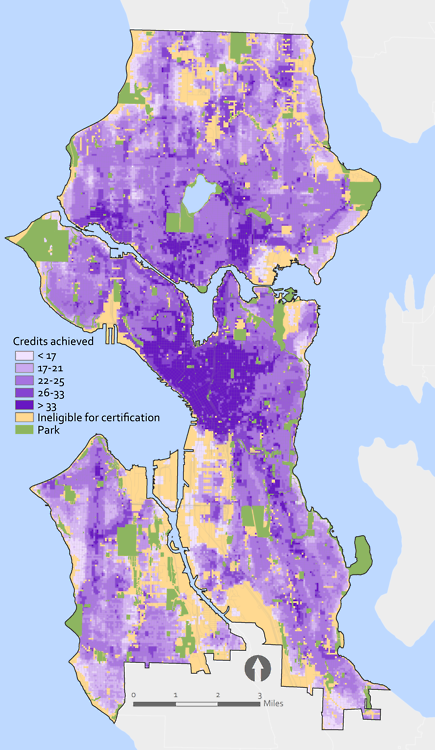

I developed a GIS methodology for applying the LEED-ND criteria to an entire city and scored Seattle as a case study. It’s purely theoretical, since certification is an option only for sites that have new construction. But there are important lessons in what we’ve already built. If an entire city or region is evaluated on the LEED-ND scorecard, we can better understand what places—that we already intimately know—best match the type of development that the USGBC wants to encourage (assuming that LEED-ND is a good proxy for a sustainable neighborhood).

From a GIS perspective, the specificity of the LEED-ND credits made things interesting. Some credits were simply not feasible to evaluate, either because the data were not available (like building façade details or energy and water use) or the credit can’t apply to an existing site (habitat restoration, for example). Sometimes I adapted the nuances of the credit to the data available. In short, my method used GIS data to evaluate whether any given point in the city meets or fails the specific requirements of each credit and then summed these data layers to determine the final score. I divided the city into a grid of one-acre sites—a fine enough resolution to produce a meaningful surface raster, but large enough that it resembles the scale of real-world projects. (For those interested, there’s more about my methodology here.)

Enough about the nitty gritty. Let’s get to the results. (Download a full summary poster pdf here, or view the poster image here.)

The suite of credits I evaluated account for about half of the total points available and emphasize walkability, transit access, parks and open space, income diversity, and residential density. Neighborhood qualities like mixed uses, a variety of housing typologies, and frequent bus service factor heavily in the final map. With this in mind, it’s no surprise that some of the areas scoring highest in my analysis were neighborhoods like University District, Ballard, Pike/Pine on Capitol Hill, Mount Baker, and the Downtown Central Business District. These are places where a mix of housing, businesses, shops, and public spaces encourages you to go by foot or bus instead of car—a pattern of development that can reduce per capita carbon emissions and sprawl while increasing physical activity and health.

Most of us are probably familiar with this narrative, as urban sustainability has become pretty mainstream in the past few years (thanks in part to LEED-ND). But using tools like GIS to visualize where that kind of development already exists, and what places might be well suited for a rating system like LEED-ND, has a lot of untapped potential. A developer interested in building a LEED-ND project could select a site that already fulfills many of the program’s spatial requirements. A planner can look at high-scoring neighborhoods and ask: Do we like these places? Is it fitting that this is what the USGBC is rewarding, or should we be encouraging something else? Most of all, this cursory survey of Seattle shows how valuable GIS can be in each step of the LEED-ND process. The more we can grease the wheels of this kind of development, the more we can produce neighborhoods that are equitable, encourage physical activity, and address the challenges of climate change and resource scarcity.

For more maps and information, check out gradingthegreencity.com.

>>>

Nick Welch is pursuing a Master’s in Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University in Medford, MA. His focus is on sustainability planning, neighborhood development, and geospatial analysis. Examples of his work can be found at nicolaswelch.com.

Density And Affordability Go Hand In Hand

Density and affordability: To become a truly sustainable city Seattle needs more of both, but is that best of both worlds possible?

One camp argues that if you want to make housing more affordable, the best thing you can do is build as much housing as possible so that prices will fall due to supply and demand. All other things being equal, this is no doubt true. However in practice, new high-density housing tends to be relatively expensive, and in some cases may cause the displacement of existing low-income housing. And thus the opposing camp argues that dense redevelopment is an affordability killer. But they ought not to blame density itself.

Inexpensive density has existed in cities throughout history, and is arguably the most prevalent form of housing on the planet today. Of course some of that is unacceptably subpar—a.k.a. slums—but the point is nothing about density precludes affordability. And in fact, dense housing is inherently cheaper because it requires less construction, less infrastructure, less operational energy, and less land per occupant.

Nevertheless, in growing, economically vibrant cities like Seattle, new market-rate housing—dense or not!—is typically not affordable to a large portion of average households. This has two root causes:Â high demand, and high cost of production. Again, density is not the culprit.

Demand is why the most successful cities have always been the most expensive cities. People recognize a city’s value, and they are willing to pay a premium to be there. There’s nothing to be done about it, aside from intentionally destroying a city’s economy and livability. Densification is the result of demand and rising real estate prices, not the cause.

Regarding housing production costs, over the past several decades the cost of labor and materials to produce housing has risen faster than the average incomes of most of the U.S. population. That combined with the high price of land in desirable cities adds up to a cost that can put new housing out of reach for perhaps the lower third or more of households.