The assignment is to offer a ‘solution’ in 400 words or so. But my solution takes one word: density.

But I know that’s not good enough, so I’ll try to explain how I think more people living closer together can “heal the planet.†I will reprise my Urbanist Creed.

City life — lots of people living close together — is healthier, creates less damage to our air and water, is a more efficient use of land and energy, and fosters social cohesion and community.

The division between public and private realms is conceptual not physical—that is, we can live close together and still have privacy. We can build cities that allow every resident or visitor to move between the public and private realms at will, affordably, and with ease. Privacy and choice are important and cities can create more rather than fewer choices.

Aggregating the way we meet our basic needs — eating, drinking, housing ourselves, clothing ourselves, and entertaining each other — makes common sense, is more efficient than land use policies that separate use, and will build stronger connections between people of every race, class, sex, and orientation.

Living close together and meeting our needs close to home, makes getting around easier. By bringing the things we want and need closer to where we live we ensure less time traveling and more time living. And such a living arrangement creates positive interdependence. When we depend on each other, we realize we’re only as good as the least among us.

That’s why many of our region’s greatest economic and social problems — poverty, crime, homelessness, poor academic performance—can be significantly and positively impacted when people live closer together because, if nothing else, our proximity to each other makes the suffering of our fellow person intolerable.

So if healing is what we’re looking for let’s get closer together. It will be uncomfortable for sure. Some views will be blocked. Some noise will be made. Some smells will be smelled that we don’t want to smell. But breathe it in! Roll around in it! Jump on it and hold on with both arms and both legs. It’s called density, and it’s going to save us all.

>>>

Roger Valdez is a Seattle researcher and writer. He recently read through Seattle’s land use code and blogged about it.

S400: Tax Exempt Status For Used Bookstores

Note: I’m debuting the S400 series with this non-wonky and whimsical “solution” to make it clear to would-be contributors that (almost) anything goes. Bring on the quirky and far-fetched! Citytank won’t be checking your urban planning credentials.

Used bookstores are urban treasures and I don’t want to live in a city without them. An inherently dubious business to begin with, brick-and-mortar used bookstores have been driven even closer to the brink by the onslaught of the interwebs. But I believe the public benefit of used bookstores justifies public investment in saving them, and granting them complete tax exempt status would be one straightforward way to help.

Used bookstores enable discoveries like this: Scanning the sociology section at the Bookworm Exchange in Seattle’s Columbia City neighborhood recently, my eye was caught by a red and black paperback spine with the title “URBANMAN.” Published in 1973, it’s a collection of essays about “the psychology of urban survival,” with a cover illustration that could easily pass for contemporary poster art (hello Shawn Wolfe).

In the last essay, Christopher Alexander of Pattern Language fame writes about the loss of intimate relationships in cities:

Any observer comparing urban life with rural or preindustrial life must be struck by the extreme individualism of people who live in cities…Â It is a pathological overbelief in the self-sufficiency and independence of the individual and the individual family, and a refusal to permit dependence of any emotional weight to form… The individual who is technically autonomous, whose dependencies are all expressed in money terms, can easily make the mistake of thinking he, or he and his family, are self-sufficient. Now, naturally, people who believe that they are self-sufficient create a world which reinforces individualism and withdrawal.

Unearthing that slice of 38-year-old wisdom would be highly improbable by any means other than randomly browsing a used bookstore. Googling the above text yields zero hits.

Learning is a non-linear process. The best discoveries are often made by mistake, not by online recommendations derived from multivariate analysis of consumer preferences. And public libraries too, can be stiflingly rigid compared to a typical messy and unpredictable used bookstore.

What’s more, used bookstores are just the stuff that can help counteract the kind of withdrawal Alexander describes. You have to go out of the house. You see people and maybe even talk to them about books. Perhaps you get hit with an idea from outside your socio-intellectual bubble, or from the forgotten past.

Used bookstores recycle both ideas and material goods while they enhance the vibrancy of walkable urban neighborhoods. That’s sustainability.

We let churches go tax free. So why not used bookstores? And where better to grant tax exempt status to used bookstores than in the home of Amazon.com?

A few weeks ago I found the 1972 classic shown below at Half Price Books on Capitol Hill. Suffice it to say too bad nobody paid much attention back then and we proceeded to ridicule Jimmy Carter’s sweater and elect Ronald Reagan so that everyone could live in denial about limits to growth for few more decades and we could dig our hole that much deeper.

New Series: S400—Solutions For Cities In 400 Words

Last March Citytank launched with the C200 series on why cities matter in 200 words. Over the following weeks, some 70 authors contributed.

Summer’s over and Citytank is back from a mental vacation, recharged, and primed for a C200 followup series: S400

The “S” is for solutions. In 400 words.

C200 was (mostly) about why cities matter. Building on that premise, S400 will be about solutions—specific solutions for how we can better leverage the potential of cities to both improve people’s lives, and heal the planet.

Solutions big or small; pie-in-the-sky or implementable tomorrow; local or universal; liberal or conservative. Solutions ranging in scope and scale from creating a new agency for regional planning, to scrapping Seattle’s land use code and starting over, to banning leaf blowers, to painting all sidewalks purple. Anything goes as long as it has some redeeming value (i.e. if it’s stupid it had better be funny).

Got an idea about how to make cities work better? Citytank wants to hear about it, ASAP. The series launches soon. Time’s a wastin’. Please send your S400 thoughts, proposals, and drafts to: tanked@citytank.org.

The 400 word limit is a loose guideline, intended to help keep the pieces tight and focused on one idea. If you need more words that’s fine, but remember, less is often more. And images add a lot.

When I first envisioned the C200 series I never expected it to draw so many great contributions from so many great people. Can S400 do the same? I’m hopeful that together we can create something truly blogalicious. And maybe even help cities make progress to boot.

A Big Idea For Seattle: The Weather Machine

Note: For their September 2011 issue Seattle Magazine asked “dozens of prominent locals” to contribute a big idea, one favorite, money-is-no-object project that could “fix” Seattle. Here’s mine, the raw and uncensored version.

For those who tread the wonky realms of urban planning, all the best big ideas for Seattle could be neatly summed up in a single directive: Do like Copenhagen. Next please.

So allow me to propose a big idea that is way, way bigger than any of that, an idea that’s not afraid to take on the absolute worst thing about Seattle. No, not gridlock. No, not self-righteous cyclists. Nope, not even excess earnestness. Seattle’s lamest factor by far is its relentlessly damp and gray, cruelly calm, but ultimately suffocating, weather.

And the solution? A weather machine.

I got the idea from my wife who got the idea from the classic daytime soap General Hospital, that back in 1981 had arch villain Mikos Cassadine plotting to achieve world domination with a weather machine that could create blizzards. All we need is a similar machine that brings the weather of Santa Barbara to Seattle. Google could totally do it.

And the thing is, not only would some decent weather help snap us out of our collective vitamin D-deficiency-driven lethargy, it would also go a long way towards improving the stuff we urban planners endlessly fuss over. Because when it’s nice out lots more people walk and bike. The streets come alive with actual human beings exposed to the world rather than cloistered within shiny glass and metal boxes. Sidewalk cafe culture flourishes. People leave their homes, talk to each other face to face, and create this mythical thing we like to call community. Plus you get to wear sunglasses all the time.

But more importantly, I know I’m not the only one who’s thoroughly perplexed about how a city so full of smart people can be so timid when it comes to the mounting need to reshape Seattle’s built environment for the 21st Century. There is a remarkable lack of bold leadership. I’ve run out of theories except one: the weather. Can there be any other explanation for the thirty years it took to get light rail? Seattle weather turns backbones to mush.

Now, the one minor downside of my big idea is that it doesn’t exist yet. And so just in case the geniuses at Google fail to deliver the weather machine, I’ve got a plan B: Fires. That’s right, great, big, nightime bonfires in strategic locations throughout the city. Picture the vibrant social scene that would ensue around a roaring, open blaze in an empty parking lot in Pike/Pine on a drizzly winter weekend night. Bake the soggy gray right out of us, those fires would.

Alas, the fire idea would no doubt come up against our timidity complex—Catch 22. So, not to be defeated, I’ve got one last fall back, a maybe not so big, but truly humane idea for the City of Seattle: Ban effin’ leaf blowers. There really isn’t any explanation necessary, is there?

Future-Ready Cities: Why the capacity and willingness to change trump everything.

Note: This post originally appeared at alexsteffen.com.

< Rendering from the OLIN team's award-winning submission to the International Living Building Institute's Living City Design Competition >

Anybody who thinks at all seriously about climate and our other planetary crises has probably thought at least a little about their own choices and prospects.

Many of us wonder whether we live somewhere that will be a good place to be in 10 or 20 or 30 years. People are starting to think about questions like, What will the local climate be like in coming years? Will the local infrastructure prove rugged in the face of natural disasters and economic shocks? How good is the water supply, the energy supply, the food supply? How heavily dependent on fossil fuel is the local economy? What will sea level rise mean to this place? A few people are actively relocating solely for big picture reasons, but right now, I hear it more often as a concern, one piece of the calculus used in making life choices.

So, how do we choose?

There are some places that are dealing with natural attributes and human legacies that will be almost impossible to address (Bangladesh, for instance, will find it very hard to adapt to sea level rise under the best circumstances; many auto-dependent American suburbs will likely experience economic distress as resource and energy costs rise; the US Desert Southwest will be extremely stressed by both anticipated heat waves and fossil-fuel dependent land uses and economies). How temperate the local climate is likely to be, how stable the surrounding ecosystem services are likely to remain, how wise (or lucky) the region has been in growing energy-efficient cities, how rich the local people are, and how much strength and integrity their national governments have — all these will matter, undoubtedly.

But I’ve come to the conclusion that readiness to act matters more than any of these. Places that invest boldly in the next decades in ruggedizing their systems, growing civic resilience and building up the local capacity for innovation, adaptation and rapid cultural change… these are the places that will be most prepared for the storms on the horizon.

Being a city region ready to meet the future (whatever it looks like) is more important than being luckiest in location or wealthiest at the moment. Successful engagement with future turmoil will demand leadership, strong civic cultures, commitment to change, tough choices, aggressive action on big systems. No city out there is moving fast enough, yet, but some are beginning to show signs of understanding the scope, scale and speed of the change demanded of them. Others look great now, but are changing only incrementally and slowly. There comes a point where lack of action means further incremental change can no longer keep up with exponential problems.

Personally, I’d rather live in a city that’s moving fast to meet the future, than one that started father ahead, but is stuck and complacent, or simply unwilling to go beyond mere incremental change. If I became confident that any city was in fact poised to be a real global leader, I’d move in a heartbeat.

I know I’m not alone. In fact, I suspect that a city that really through itself to the forefront of urban innovation (and had a clear commit to further innovation ahead) would find itself a magnet for civic talent, entrepreneurial efforts and global investment.

It may be a city few of us think of a leader now (though I think several well-established metros are positioned to rocket ahead, if they ignite bolder strategies). It may be a city in the developing world, though most of the obvious lead contenders have problems at least as big (and politics at least as stuck) as any of their developed world competitors. I doubt, unfortunately, that it will be an American city, unless an absolutely extraordinary leader comes to the front in one of them: the gridlock is too severe, the legacy of sprawl too large, the civic culture too frayed and poisoned. I would love to be proven totally wrong.

Wherever it may emerge, the edge a leading bright green city gains in the next 20 years could put it in a position of increasing prosperity for a century, even in the midst of hard and turbulent times. The solutions it invents and tests could also benefit the entire world, even help smooth some of the rough waters ahead. The best possible scenario would be one in which several (or many) cities hurl themselves into fierce competition to lead in a bright green urban boom.

>>>

Alex Steffen is one of the world’s leading voices on sustainability, social innovation and planetary futurism. He is a writer, public speaker and strategy consultant.

Hey there Seattleites, remember back in late fall 2009 right after McGinn got elected mayor when Alex Steffen challenged the City of Seattle to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030, and then the City Council adopted that idea as a 2010 priority, and then Councilmember Mike O’Brien convened an army of volunteers to address eight components of greenhouse gas emissions, and then the Office of Sustainability and Environment (OSE) contracted out a carbon neutrality study, and hey, have you been wondering what’s up with all that lately?

Well, that carbon neutrality study by the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) is done, and it’s action packed. The proposed scenario would achieve steep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions in three main buckets: (1) transportation mode shift away from private autos: (2) greater energy efficiency in both vehicles and buildings: and (3) switching to less carbon intensive energy sources.

< Greenhouse gas emissions for the Seattle carbon neutral scenario; Stockholm Environment Institute >

In more detail, here’s what the study says could achieve a 90% reduction in Seattle’s per-capita emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050 compared to 2008 levels:

- 50% reduction in travel by light duty vehicles (replaced by walking, biking, and transit)

- 50% increase in vehicle energy efficiency

- Electrification of 80% of the vehicle fleet

- 50% increase in building energy efficiency overall

- By 2030 all new buildings achieve 75% energy savings

- Energy retrofits penetrate 90% of all existing buildings and achieve 40 to 75% energy savings

- 90% of existing residential buildings and all new single family use electric heat pumps

- For new multifamily buildings, and for new and retrofit commercial buildings, half use district energy, and half use electric heat pumps

The proposed scenario was intended to be aggressive, not over-the-top, but no doubt the above bullet points would take some serious doing. To achieve the required mode shift to transit, for example, the assumption was a five-percent annual increase in transit service from 2010 to 2020 followed by a constant annual increase (equal to the 2020 increment) thereafter. That adds up to a huge boost in transit service, and right now we may be headed in the opposite direction. The assumed scale of building energy retrofits is way, way beyond anything that has ever been attempted, and would require a massive up-front investment.

Of course, that’s the reality of addressing climate change. We’re actually going to have to make an effort, imagine that. We could be—and should be—aggressively moving forward with the above strategies already.

There’s tons more fodder for debate and deeper questions raised by the SEI study (e.g. What happened to the 2030 target? What about consumption-based emissions? Can we afford it? etc.), and we can expect to be hearing a lot more about all of it as OSE gears up for a major update of Seattle’s Climate Action Plan over the coming year. For now I’ll take you back to where it started and leave you with the video below, Alex Steffen’s July 2011 TED talk on carbon zero cities:

Note: This post originally appeared on Sightline, and is part of their series: Making Sustainability Legal. One point to add: We should also consider how the taxi license shortage could be leveraged to increase the sustainability of the fleet, e.g. by giving priority or reduced fees to higher mileage cabs like Priuses. – Dan Bertolet

What if the Northwest’s cities legally capped the number of pizza delivery cars? What if, despite growing urban population and disposable incomes, our Pizza Delivery Oversight Boards had scarcely issued new delivery licenses since 1975? Pizza delivery would be expensive and slow; citizens would rise up in revolt.

Substitute “taxicab†for “pizza delivery†and you have a reasonable facsimile of the taxi industry in Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, BC: tightly restricted taxi numbers, high fares, and low availability.

Plentiful, affordable taxis facilitate greener urban travel. They help families shed second cars, ride transit more often, and walk to work on could-be-rainy days. They fill gaps in transit systems and provide a fallback in case of unexpected events.

In the Northwest’s largest cities, however, local ordinances enforced by taxi boards suppress the entry of new cabs onto the streets. They impose arcane and ultimately farcical management principles reminiscent of Soviet planning. Imagine teams of pizza regulators pawing through discarded receipts and pizza boxes to determine whether demand for pizza delivery markets are “oversaturated,†and you won’t be far from the truth. Restricting taxicab licenses undermines passengers’ mobility, local economies, and—by encouraging driving—our natural heritage; uncapping cabs would allow market competition to bolster all three.

As shown in the figure above, at present, the Northwest’s largest cities have fewer cabs per capita, and higher fares, than many US cities. Seattle’s 1.4 cabs per 1,000 residents is twice Portland’s 0.7, and well above Vancouver’s 1 cab per 1,000. But all our cities lag. Washington, DC, has more than 12 cabs per 1,000 residents; Las Vegas has almost 6; and San Francisco has 2. Meanwhile, the cost of a typical, five-mile trip is $16.50 in Portland, $17.25 in Seattle, and $21.57 in Vancouver. Washington, DC’s typical fare is just $11.50.

Consider the efforts of Portland’s Transportation Board of Review, which has the power to issue new taxi licenses but is also charged by city law with monitoring “market saturation factors.†It is supposed to avoid market oversaturation, something every other market—from pizza delivery to home remodeling—manages to do just fine on its own, without benefit of a board. In Portland, the rules actually require applicants to prove that a new taxi license is needed. Imagine if Pizza Hut had to demonstrate to the Pizza Delivery Board that it needs another driver for the Super Bowl.

In Vancouver, the Passenger Transportation Board‘s rules are slightly more flexible than Portland’s. They have allowed a trickle of new cab licenses over the years, but they have screened out many applicants, too. A Vancouver cab company seeking a new license is supposed to prove the taxi market isn’t already too full, and that can be a complex question to answer. In other markets, entrepreneurs figure out the answer to their own satisfaction, then see if they’re right by risking their own time and money. New pizza parlors do not have to show city regulators that their delivery service is needed.

Worse, in Vancouver, cab companies may petition against a competitor’s new license. When Pizza Hut applies for an extra delivery license for the Super Bowl, in other words, Domino’s has a right to challenge the application. In 2010, the board rejected some 43 percent of requests for new permits, despite the city’s high taxi fares and paltry cab numbers.

Seattle’s Department of Executive Administration, like taxi boards to the north and south, tries to divine the number of taxicabs Seattle can support without oversupplying the market (whatever that means). Its method is to comb through an enormous database of “weighted average taxi response times†to look for signs that wait times are getting worse. Making the heroic assumption that Seattle’s status quo of long waits and fruitless cab hunting are acceptable, it looks for signs of further deterioration before considering new licenses.

A better test would be whether anyone is willing to pay for a taxi license. Guess what? Seattle medallions currently trade for $100,000, when they’re for sale at all. When the city offered 15 new licenses for wheelchair accessible taxis in 2009, 723 drivers applied. Vancouver taxi licenses have sold for up to CDN$500,000. (In New York, taxi medallions were selling for close to $1 million in June.) The explanation of these bubble-like prices is economics: restricting taxi supply increases the profitability of each cab. Holders of taxi licenses can fill their cabs more of the time and keep the meter running.

In the Northwest as across the continent, taxi regulation is dominated by license caps and fixed rates, but that isn’t the only way. Washington, DC, has no limit on the number of cabs. It has plenty of taxis and low prices. The capital city does regulate taxis, insisting, for example, that drivers and vehicles meet safety criteria, that fares be clearly posted, and that meters be accurate. But DC law imposes no lid on taxi licenses. That’s good sense. When we import that approach to Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, we’ll have more-robust urban taxi fleets and we’ll be able to leave our own cars home more of the time.

>>>

Guest blogger Vince Houmes of Seattle is a longtime Sightline supporter and hobbyist policy researcher.

>>>

Sources of charts: Data from the Chicago Dispatcher, with updated city populations (from Wikipedia) and updated numbers of Seattle and Vancouver taxis. An “average trip†is 5 miles long, with 5 minutes of waiting. Per-capita numbers are for city, not metro, population. Vancouver cab prices vary slightly, but a reasonable estimate may be found here.

Save our Soul {SOS} Seattle: Why the Seattle arts and heritage community should vote to reject the tunnel

Introduction

Six years ago, when I began working as an “artist in transportation,†I was resolutely apolitical. My sole interest was to explore how the 520 Bridge Replacement Project would impact the Arboretum’s rich cultural heritage, natural beauty and living collections. I remember explaining my ideas to a prominent Seattle arts leader. He politely scoffed. “The 520 is about big cars, big money and big politics,” he said. His meaning was clear: There’s no place for an artist in this debate. I was stunned.

Since then, I’ve come to see his point. It is incredibly difficult to influence the outcome of a mega transportation project. To have any hope of doing so, you must engage politically. So I have. Over the past few years, I’ve attended so many meetings that I now consider public forums to be my studio space. I volunteer my time to do this work because transportation projects are largely exempted from percent-for-art programs, and yet they’re as much about art and history as they are about counting cars.

Or they should be. Collectively, the cultural community understands our history as manifested in historic buildings and landscapes; we can envision the impact on these spaces in all its complexity. When it comes to advocating for our city’s cultural spaces and heritage, our knowledge and expertise are critical.

In the essay that follows, I’ve done my best to explain the aspects of the tunnel project that I think the cultural community will care most about. The tunnel debate has been intensely polarizing, and up to now, I’ve tried to stay open to the idea that we could protect Seattle’s cultural resources under any plan, but the more I learn about the tunnel, the more I realize that it puts too much at risk. We need to reject the tunnel now.

Your ballot has arrived.

Please vote.

Protect Seattle’s arts and heritage future.

Reject Referendum 1.

Reject the Tunnel.

Great places: smart density as part of economic flourishing

Note: this post originally appeared on Grist.

< Bring people together in a great place and great things happen. >

So far I’ve written that great places are green and groovy. (Yeah, I said groovy.) Lest I make the whole notion sound like a smelly commune, though, it’s worth noting that great places are also fecund: They generate economic and social capital. Done right, density can be an engine of prosperity. Business executives should love great places just as much as hippies like me do.

Here’s the basic idea: When smart, skilled people start to gather in a place, the process becomes self-perpetuating. More smart, skilled people show up to be near the others. And the more smart, skilled people you get close together, the more you reduce transaction costs and increase “knowledge spillover,” which leads to commerce and innovation. That’s true not only for individuals but for industries and research institutions (universities, labs, etc.). In economic nerdspeak, this phenomenon is known as the “economies of agglomeration.” It concrete terms, it means, as Ed Glaeser put it recently, that “wages and productivity rise with density.”

There’s a lot of research going on around this now, and I don’t want to overstate how settled the scholarship is, but the basic idea is pretty intuitive. After all, the metropolitan areas where people and businesses cluster are the engines of the U.S. economy. America’s top 100 metropolitan areas cover about 12 percent of its land but produced, in 2008, around 75 percent of its GDP. The top six metros alone generated more than 25 percent. According to a 2009 analysis by Brookings, in 47 out of 50 states, the bulk of the economic output comes from metropolitan areas. In 15 states, a single large metropolitan area produces the majority of economic output. Cities are also the source of most patents, a reasonable proxy for innovation.

So cities are already where the economic action is. And managing metros well is only going to get more important in coming years. Consider a few demographic and economic trends that are driving accelerated urbanization: The U.S. population is getting older on average; Baby Boomers are retiring, looking to downsize and get closer to amenities. Men and women are marrying later, meaning there are lots more young, single people looking for vibrant job and mating markets. When they do get married, they’re having fewer kids (a trend exacerbated by the recession), and smaller families tend to live closer to urban cores.

In short, lots of people are headed for cities, and density, which declined in the ’80s and ’90s, is destined to head back up. And while economies of agglomeration are not as strong for old-school, land-intensive businesses like heavy manufacturing, warehousing, and big-box retail, for the innovative service and knowledge jobs that increasingly dominate the U.S. economy, getting people in close proximity is a huge boost. All those incoming people could be an enormous asset for cities that know what to do with them.

So what can cities do to maximize the benefits of this inflow? What makes for an economically great place? I asked Bruce Katz, head of Brookings’ excellent Metropolitan Policy Program, and he emphasized that smart growth alone is not enough. “What you want is great places that are built on great economic bases,” he said. “The two really need to go together. What I argue for is economy-shaping, talent-preparing, and placemaking, all together.”

So smart density cannot yield economic flourishing all on its own; cities need to focus on their tradeable sectors, research institutions, and worker training programs. Nonetheless, smart density lays the groundwork for agglomeration economies to emerge and can accelerate and strengthen them when they do. So how can places do density right, to encourage great (economic) places to take root and grow?

Trying to accommodate population inflow with low-density sprawl doesn’t work. First, it increases the cost of infrastructure (roads, sewers) and services (police, fire departments). Given the grim state of federal and state budgets, “the fiscal arguments matter even more today,” said Katz. “If you don’t have those costs, you’re able to invest in what matters. Density yields fiscal rectitude.”

Second, sprawl creates congestion. And as the 2010 Urban Mobility Report reveals, the costs of congestion are getting out of hand: “measured in constant 2009 dollars, the cost of congestion has risen from $24 billion in 1982 to $115 billion in 2009.” If that doesn’t convince you, long commutes also cause “obesity, neck pain, loneliness, divorce, stress, and insomnia.” People tend to overestimate the hedonic benefits of owning a car, in part because they underestimate how much being in traffic suuucks.

And third, sprawl thins out the labor pool, which reduces innovation and productivity. Conversely, density that’s well-served by multi-modal transportation systems has the effect of “thickening” the job market, giving more people better access to more opportunities. A 2000 paper by scholar Robert Cervero found that “employment densities and urban primacy are positively associated with worker productivity.” (There’s a bumper sticker for you.)

Density served by effective transit systems — “accessible cities” — can also serve the cause of economic justice, by widening the “laborshed” of low-income people without cars, but “you really have to be intentional about that,” Katz notes. “You’ve got to build in inclusionary zoning.” But that’s probably a subject for another post …

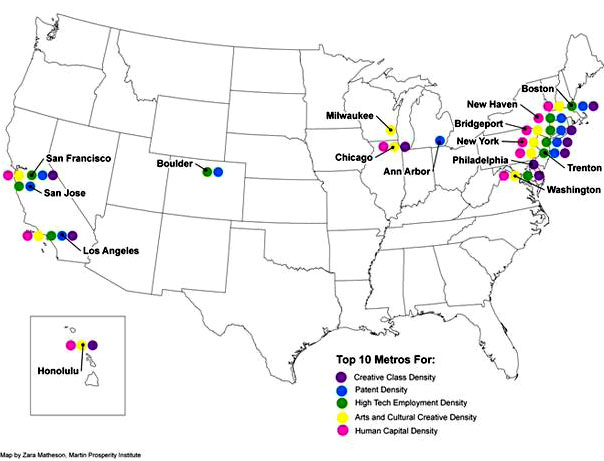

Anyway, accessible cities are attractive to the very people cities need to attract these days: the educated, the skilled, the creative, the entrepreneurial. What else do those folks want out of a place, besides robust economic opportunities and walkable, liveable communities? Well, they want urbane and tolerant culture, plentiful amenities, and competently delivered services. In short, they want great places. As Richard Florida argued in a series of posts at The Atlantic last year, “human capital density, creative class density, artistic and cultural density, [and] high-tech and innovation density” are often found in the same places:

That’s no accident. The brightest and most ambitious people tend to follow one another to the same places. They cluster.

Obviously, one question for progressives is how to produce more bright and ambitious people. That gets into education policy, pre-natal care, and all sorts of other areas. But another, equally important question is, how can we create more places where such people gather and flourish? How can the benefits of smart density, reflected in the map above, be spread more widely? What can a national political movement do to empower metropolitan areas to become great places, so that more Americans have a chance to live in one? That’s what this series is about; that, I argue, is what progressive politics should be about.

Obviously, one question for progressives is how to produce more bright and ambitious people. That gets into education policy, pre-natal care, and all sorts of other areas. But another, equally important question is, how can we create more places where such people gather and flourish? How can the benefits of smart density, reflected in the map above, be spread more widely? What can a national political movement do to empower metropolitan areas to become great places, so that more Americans have a chance to live in one? That’s what this series is about; that, I argue, is what progressive politics should be about.

>>>

David Roberts is staff writer for Grist. You can follow his Twitter feed at twitter.com/drgrist.

Writing Code For More Sustainable Neighborhoods

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Crosscut. Hint: Food for thought regarding Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan Update.

>>>

< Mayor McGinn and Councilmember Conlin announce the new recommendations; photo by Chuck Wolfe >

A recent joint announcement of recommended regulatory-reform measures for neighborhood development had Mayor Mike McGinn and Seattle City Council President Richard Conlin focusing on creating new jobs. That angle was the attention grabbing headline in the major media.

Ordinarily, reforms of urban land-use regulations come about after a lot of pushing and pulling by consultants and organized pressure groups. These reforms were different. They embraced community input by putting together a roundtable of interested parties to come up with some evolutionary Code updates, deriving from the issues de jour of recent years — including backyard cottages, revised approaches to multifamily development, parking requirements, street-level retail, and other arcane elements of urbanist lore.

This month’s joint announcement is the outcome of a six-month process, discussed in detail below. It meshes with a March 2011 City Council resolution adopting guiding principles for strengthening and growing Seattle’s economy and creating employment opportunities. The recommendations were released for public review and comment, due by July 25.

Full disclosure: I am an active roundtable member, which gave me a ringside seat but also makes me an advocate.

The roundtable behind the recommendations was composed of a broad alliance of business, environmental, and neighborhood representatives. Variants of the roundtable were convened by Mayor McGinn for initial conversations early this year, and a core group worked collaboratively on the announced recommendations. In a departure from past governance practices, the group is not an appointed “blue ribbon commission,” nor does it have staff. It has met regularly (often many times per month), vetted issues and approaches, and worked with city officials to brainstorm solutions.

The current recommendations are in reality an early stage of the roundtable’s work, and in the eyes of some group members, only a small tilt towards further revisions to the Land Use Code. Yet the proposals evince some sense of today’s urbanism agenda — a move away from prescription and favoring implementation of tweaks, clarifications, and small expansions of certain non-traditional housing, business, and multi-modal transportation initiatives already under way.

Further, given the urgency of enhancing employment, the recommendations embrace immediate, simplifying measures, intended to reduce complexity and increase flexibility, in turn decreasing the costs in time and money of starting and maintaining businesses and building new, more affordable housing.

While the initial menu of fixes is designed to avoid duplication and enhance the prospect for new construction, the group will continue to work on longer term issues in association with pending revisions to Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan. Those revisions are mandated by the Growth Management Act and championed through a dynamic update process recently launched by the Department of Planning and Development and the Planning Commission.

The group’s goal is broad and ambitious: to help Seattle residents live closer to where they work. The starting place is to simplify and update the city’s Land Use Code, what Sightline’s Eric de Place calls “making sustainability legal.”

This broader effort is akin to something that I first suggested here in Crosscut amid the elections of 2009. I proposed a frank recognition of traditional land use dilemmas in the City and a move towards contemporary land use regulatory approaches focused less on incremental brush wars and more on holistic and sustainable tools implemented elsewhere. Examples of this new approach, I wrote, are form-based codes, citywide transit-oriented development policies, and ongoing integration of transportation, land use, and underlying natural systems.

Let me now provide a summary of the announced recommendations. More detailed discussion of each recommendation (with the addition of a proposed modification for height measurement) appears in public notice materials assembled by DPD here as summarized from DPD Director Diane Sugimura’s Report and Recommendations, which urges adoption of the Roundtable’s recommendations.

Encourage Home Entrepreneurship The Roundtable embraced the assumption that the home-based business is an incubator for new ideas which create jobs. The recommendation would allow property owners to operate home-based businesses (“home occupations”) in any structure, as long as impacts to surrounding properties are minimized, and any associated alterations to structures are permitted in the underlying zone. Other new provisions would allow home-based businesses to advertise on the internet, allow up to two non-resident employees (currently limited to one), and allow more flexibility for weekday deliveries with limits focused on heavy vehicles.

Concentrate Street-Level Commercial Uses in “P-Zones.” The Roundtable acknowledged that ground floor commercial uses make sense in shopping and other pedestrian areas, and is a major premise of the reinvented and walkable American city going forward. However, recessionary times have made clear that more flexibility is needed outside of those areas to build buildings without ground-floor commercial spaces. This recommendation will drop the ground floor commercial requirement outside of pedestrian-overlay (P) zones, and would apply to approximately 80 percent of Commercial (C)- and Neighborhood Commercial (NC)-zoned frontages on arterials throughout the city.

Enhance the Flexibility of Parking Requirements The Roundtable recognized recent debates over the cost of parking, and agreed with the premise that as Seattle’s transit service improves, demand for on-site parking will shrink. This recommendation will allow the market to determine how much parking should be provided in locations within one quarter mile of good transit service (generally, those with at least 15 minute headways). It eliminates minimum parking requirements for residential or non-residential uses in such locations (such minimums currently apply only to residential uses within urban villages). In addition, this recommendation modifies minimum parking requirements for major institution uses in urban centers to be the same as other nonresidential uses.

Allow Small Commercial Uses in Multifamily Zones The Roundtable acknowledged the trend towards re-establishing the small corner store amid the urban fabric. Historically, residential zoning has often been an impediment to locating such small commercial uses close to where people live. This recommendation would allow small corner stores in “Lowrise 2 and 3” multifamily zones in urban centers and light rail station area overlay districts — thereby providing additional retail opportunities already present in “Midrise” and “Highrise” multifamily zones.

Expand Options for Accessory Dwelling Units. The Roundtable recommended additional flexibility for Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) through allowance of backyard cottages on “through lots” (lots that front two streets), essentially providing for a “backyard” in cases where the Code has historically interpreted two front yards. The recommendation also allows more flexibility for the height of backyard cottages on sloping sites and clarifies that ADUs are allowed in all housing types (including townhouses, rowhouses, and in multifamily housing in NC zones).

Mobile Food Vending/Temporary Uses The Roundtable endorsed a continuation of flexibility to non-permanent uses which help enliven neighborhoods. This recommendation would allow vending carts on private property where other commercial uses are permitted (“Lowrise 2 and 3” zones in urban centers and light rail station areas, and in “Midrise” and “Highrise” multifamily zones). Example: a coffee cart in front of an existing restaurant. This recommendation would also extend the permitted days and hours of farmers markets, and make temporary use permits easier to obtain for street food and other vending to expand their duration period. It complements other street food proposals under consideration that address activities within public rights-of-way.

Change State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) Implementation to Avoid Redundant Review and Provide Amended Review Thresholds. The Roundtable recommended that the city take advantage of opportunities to streamline and combine SEPA review with other aspects of regulatory review for proposed residential and mixed-use projects in designated growth centers, such as urban centers and light rail station areas The goal of SEPA is to minimize environmental impacts, but 1995, 2003, and 2009 legislative amendments to SEPA allow streamlining of environmental review to use development standards within the Land Use Code to address major environmental impacts.

This recommendation would codify SEPA conditioning authority for transportation analysis and mitigation in the Land Use Code (as a Type I, non-appealable, decision) in exchange for raising the SEPA unit and square footage thresholds for individual projects in urban centers and light rail station areas to 200 dwelling units (250 in the “Downtown Urban Center” designation ), and 75,000 square feet for commercial uses in mixed-use development. The Roundtable’s intent? By putting mitigations directly into city standards, this recommendation is intended to create more certainty that a project’s impacts will be addressed, while shortening the permit review process.

Which brings us back to the jobs theme at the press conference. As announced, this SEPA aspect of the proposal could result in 40 new construction projects with 100 to 250 units each year. The Seattle Building Trades Council estimates that 2,400 direct jobs in skilled construction trades could be created through such measures.

>>>

Chuck Wolfe, a Seattle environmental and land-use attorney, holds a master’s degree in regional planning. He blogs at myurbanist.

Bringing Sexy Back to the Comp Plan

Whether you call us the stewards, champions, or guardians of Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan, it’s undeniable that the Planning Commission has a very special relationship with Toward a Sustainable Seattle, that massive, sprawling document that guides our city’s growth. Yes, perhaps it is only a Commissioner that feels drawn to tend the Utilities Element like a prizewinning rose, or who commits the Housing Appendix to memory. But allow us to unabashedly confess to having spent many a stormy evening, glass of wine in hand, passionately debating the merits of Land Use Policy 59 or a proposed amendment’s effect on the Future Land Use Map. Say what you will, for a Planning Commissioner this makes for a scintillating evening.

Okay, we recognize that most people don’t get hot and sweaty in the same way we do when there’s talk about a major update to the Comp Plan. We get that it doesn’t titillate in the same way as do backyard chickens, or the prospect of mobile food pods, or (and this might be understandable) the placement of adult cabarets. But the thing is, it should.

For those of you who have never cracked the big brown binder, the Comp Plan is where the framework policies for all these decisions get made. This is where we lay out how we should focus new jobs and housing, and what our neighborhoods should look like. The Comp Plan guides how we invest city dollars in transit, pedestrian and bike connections, parks, libraries and community centers. In truth it is the genesis, the framework from where all big-picture land use, growth, transportation, and housing decisions start. The Washington State Growth Management Act requires it.

For those of you who have never cracked the big brown binder, the Comp Plan is where the framework policies for all these decisions get made. This is where we lay out how we should focus new jobs and housing, and what our neighborhoods should look like. The Comp Plan guides how we invest city dollars in transit, pedestrian and bike connections, parks, libraries and community centers. In truth it is the genesis, the framework from where all big-picture land use, growth, transportation, and housing decisions start. The Washington State Growth Management Act requires it.

After all, the place your backyard chickens call home is also the economic center of the region, expected to welcome at least 120,000 new residents and 115,000 new jobs by 2031, with more likely as Seattle proves an increasingly attractive alternative to the suburbs. Now is a critical time for a robust public dialogue on the opportunities and challenges Seattle faces as we grow over the next 20 years.

If you care about keeping Seattle affordable, creating neighborhoods where you can walk to what you need, prioritizing where we spend city dollars, becoming a climate-friendly city, or promoting great urban design, then it’s time to bring sexy back to the Comp Plan and get in on the major update process starting now.

What difference might it make? Consider that in 1994 light rail was a distant dream for the future, composting was for hippies, and the idea of concentrating housing and jobs around frequent transit in Urban Centers and Villages–now considered a no-brainer–was practically causing riots in the streets. Change is certain, and will bring us both new opportunities and new challenges. It’s up to us to help the city think through how we address all of these important issues and help shape the future of Seattle.

Identify your priorities for Seattle by taking the survey: Â http://www.surveymonkey.com/s/SEACompPlan.

>>>

Josh Brower and Leslie Miller are the Chair and Vice Chair of the Seattle Planning Commission. The Commission, comprised of 16 volunteer members appointed by the Mayor and the City Council, is the steward of the Seattle Comprehensive Plan. In this role, the Commission advises the Mayor, City Council, and City departments on issues that shape Seattle including land use, transportation, housing, and environmental policy.

I’ve hacked out an absurdly huge volume of words criticizing Seattle’s proposed deep-bore tunnel ever since it was first announced back in January 2009 (see list at the bottom of the post). And I have mainly hit on the big picture, that is, why the tunnel is such a bad investment given massive trends such climate change, peak oil, sprawl, public health, and evolving demographics and preferences—in short, largely the environmental point of view.

So it was gratifying to see a cadre of my favorite environmentalists—whose names are much bigger than mine—going public last week with such a powerful indictment of the tunnel. To me, the heart of the issue is summed up well in the last sentence:

What our community needs now, in these dark economic and political times, is a brave and pragmatic, “Hell, yes! We can do better than a buried highway.â€

Interestingly, however, much of their “environmental” argument concerned functional aspects. In particular, the remarkable truth that—as was first reported by Sightline, and then expanded on by the Stranger—modeling in the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) shows that in terms of traffic congestion impacts, a tolled tunnel is barely better than closing the viaduct and doing absolutely nothing else.

Continuing that line of thought, if we assume for the moment that the only thing that matters in the world is traffic congestion, then the key metric is vehicle hours of delay (VHD). The table below shows the FEIS’s projected VHD in 2030 for the tolled tunnel, the tolled elevated, the I5-surface-transit option (ST5), and closing the viaduct.

< Vehicle hours of delay (VHD) in 2030 for various options; source: WSDOT >

A few things pop out. First, ST5 is the clear winner when it comes to mitigating congestion in Seattle’s city center. Note that ST5 is the very plan that the pro-tunnel “Let’s Move Forward” campaign has disparaged as “McGinn’s surface gridlock.” Also, given the numbers showing that ST5 is a better performing solution for downtown Seattle than the State’s preferred tunnel option, it’s ironic that the Downtown Seattle Association is the largest single contributor so far to Let’s Move Forward.

Second, for the four-county region, compared to the tolled tunnel ST5 would only result in about one percent more vehicle hours of delay. Is that even within the margin of error for the modeling? Nevertheless, as reported as seattlepi.com, when the FEIS was released, State officials touted preserving regional mobility as the justification of their choice of the tunnel. And apparently seattlepi.com bought it, translating that one percent difference into a hyperbolic headline that reads “Surface-transit would clog regional traffic.”

Third, in terms of vehicle hours of delay ST5 performs better—both locally and regionally—than the tolled elevated, which was one of the official alternatives analyzed in the FEIS. Yet the State decided in advance that ST5 did not merit full consideration. By the way, that would be the same ST5 that was one of the original two recommended options that came out of the year-long stakeholder process, that has been vetted in multiple studies (here, here, here, here, and here), and that costs about a billion dollars less than the deep-bore tunnel. It’s hard not to conclude that the State’s dismissal of ST5 can only be the result of either an attempt to stack the deck, or incompetence.

Given the modeling data, an objective observer might conclude that choosing the tolled tunnel over ST5 comes down to Seattle taking one for the (regional) team. That is, Seattle’s mobility must get worse so that the region’s mobility can get better (even if only one percent better). And maybe that really could be a justifiable choice, depending on the circumstances. But I strongly suspect that’s not how most tunnel boosters who live in Seattle would prefer to see it. And it’s certainly not how most of the State’s electeds have postured on it, seeing as they passed legislation making Seattle property owners liable for cost overruns.

So then, back to the the original assumption that nothing matters more than moving more cars faster. During the latter half of the last century, that was pretty much the operative rule for transportation planning. But now we’re supposed to know better. Now that we understand the web of connections between transportation, land use, and sustainability, we should no longer accept small, narrowly focused gains at the expense of holistic, long-term solutions. For example, a two-mile underground freeway might result in a relatively small, local reduction in runoff pollution to Puget Sound, but a paradigm-shifting plan like ST5 has the potential to catalyze systemic change, and the resultant reduction in car-dependence would have a far greater cumulative positive impact.

The challenges and opportunities of the coming decades are so profound that we’ve got to do better than settle for major infrastructure investments based on last-century thinking. And to better appreciate why so many of us so-called environmentalists are stubbornly resistant to further compromise—as in, just build the tunnel because we have to do something—I would recommend Bill McKibben’s latest book, Eaarth, the thesis of which is that we no longer live on the same planet, and we better start planning our future accordingly. McKibben, founder of 350.org, recently had this to say regarding Seattle’s deep-bore tunnel:

‎The era of expensive, vulnerable, car- centric megaprojects is ending around the world, as more and more cities plan for a durable, resilient, diverse future. Not cars-in-a-pipe, but bikes, buses, and all the things that make a city a city.

If you agree, Protect Seattle Now, the campaign to reject the “tunnel referendum,” could use any support you can offer.

>>>

Still Not Digging The Tunnel Epilogue: The Dan Bertolet Tunnel Reading List:

- 01.23.09: Why The Tunnel Is So Wrong

- 01.30.09: Close the Schools, Dig The Tunnel Redux

- 02.02.09: Tunnel Head

- 03.05.09: Have Mercy

- 03.14.09: A Post About Something Inspiring. No, Really!

- 04.02.09: Drilling, Baby Drilling

- 05.12.09: “If no one wants to pay for it, why build it?”

- 05.21.09: Climate Change Doublethink

- 07.03.09: The Deep-Bore Tunnel Is A Done Deal (Just Like The Monorail Was)

- 08.13.09: Exclusive Offer: 2-mile Deep-bore Tunnel Absolutely Free! Limited Time Offer! Order Now!

- 10.17.09: One Issue

- 10.18.09: Tunnel Memorandum of Agreement Petition

- 10.26.09: A Response To The Earthquake Video

- 12.17.09: Tunnel Resurfacing

- 01.10.10: Don’t Worry, It’s Probably Nothing

- 02.04.10: Give That Tunnel Some Air

- 02.11.10: Re-branding is Magic: Meet the Tunnel+Transit Coalition

- 03.02.10: What Would Vancouver Do?

- 04.12.10: The Cost Overrrun Time Bomb

- 05.24.10: Council Should Unite Behind McGinn On The Cost Overrun Provision

- 06.08.10: Licata Nails It Re: The Tunnel

- 06.30.10: Parsing Conlin’s Tunnel Pitch

- 07.12.10: Let’s Get One Thing Straight: The Tunnel Is Not The “Green Alternativeâ€

- 07.16.10: Tunnel Mania

- 07.22.10:Â Let’s Give New Orleans Our Tunnel

- 07.23.10: Hey Tunnel Agreement: Got Transit?

- 08.03.10: Pretending That No Other Plan Exists

- 09.07.10: Cars and Cities

- 09.24.10: Only The Deep-Bore Tunnel Can Save Us From The Horrors Of City-Wide Gridlock!

- 12.16.10: Dead Tunnel Walking

- 03.20.11: Do What You Have To Do

- 03.23.11: Now That We’re On The Subject Of The Tunnel…

- 04.21.11: If Nothing Else, Maybe We Can All Agree On This: The Viaduct Is Ridiculous

- 05.11.11: What Really Causes Gridlock? Cities Do.

Dynamic Metropolitan Areas Depend on Transit, So Pass the Congestion Reduction Charge, Please

< Metro buses on Third Ave in downtown Seattle: photo by Dan Bertolet >

The Rockefeller Foundation published a report in 2008 declaring the twenty-first century to be the century of the city. For the first time in world history, a majority of the earth’s population resides in cities. Foreign Policy magazine devoted an extensive series to cities in late 2010, noting that: “The 21st century will not be dominated by America or China, Brazil or India, but by the city. In an age that appears increasingly unmanageable, cities rather than states are becoming the islands of governance on which the future world order will be built.†84 percent of Americans live in metropolitan areas, and it is within these diverse and dynamic regions that policies to nurture successful economies must be formed. Our economic competitors are now scattered around the globe; even being the best in the U.S. is no longer good enough.

Dynamic metropolitan areas, now more than ever, depend on transit systems. Urban areas concentrate jobs, culture and entertainment in ways that cause cross-pollination and innovation to flourish. Public transit systems are the arteries that allow these regions to circulate, to acculturate newcomers and immigrants, and to provide opportunity and access to all regional residents, at a scale in which automobiles are not suited. International quality of life surveys, such as those by Mercer, the Economist Intelligence Unit, and Monocle, assume that a comprehensive and convenient transit system is a part of the package for a high quality city. Needless to say, American cities do not rank high.

Several American metropolitan areas, however, such as Salt Lake City, Dallas and Denver, have made bipartisan commitments to strengthening their transit system, including significant investments in new rail transit. These metro areas realize that in the 21st century, transit investment is not a luxury, not a sidelight, not a divisive partisan issue, but a core component of metropolitan success and a measure of competent governance. Transit also responds to two emerging demographic factors: the rapidly growing elderly population, who may not be able to continue driving, and the effect of the millennial generation, which is less likely than their parents’ generation to have a driver’s license or to own a car.

The Seattle metropolitan area has led the way in transit commuting in the U.S. A Brookings Institute report noted that only four cities have lower rates of solo automobile commutes than Seattle, and transit usage increased remarkably during the 2000’s. 30 percent of commuters throughout the region chose other modes, and among workers in downtown Seattle, a recent survey showed that only 35 percent drove alone. 40 percent used public transit. The public transit that the King County Council currently has the power to protect, or atrophy and neglect. Ridership records show that over the past 15 years, public transit has transitioned from predominately trips between Seattle’s neighborhoods, to an essential component of regional transportation. Since beginning in 1999, Sound Transit has expanded to provide 70,000 customers daily with regional transit offerings. Meanwhile, ridership on Metro transit non-Seattle routes has soared, demonstrating increasing demand for regional transit service. As our freeway system has reached capacity a growing number of commuters have responded by switching to regional transit.

A robust public transit system is no longer an optional item for King County, expendable in lean fiscal times. Public transit has become an integral component of our regional economy, and increasingly a driver and enabler of further economic growth in the job centers of King County. All the discernible trends show that the importance of transit in metropolitan areas is increasing. If you support further economic development in King County, if you support integration of immigrants and low-income persons into our society, if you support retaining and strengthening our region’s competitive edge in an increasingly global marketplace, then support using the authority granted by the State to maintain funding for King County Metro transit. Support the $20 per year cab tab fee known as the Congestion Reduction Charge.

>>>

Chad Newton is an Environmental Engineer and Seattle resident.

Memo to state officials: It’s the cities, stupid!

Note: The following post originally appeared on Crosscut. This C200 post hit on similar themes.

< Seattle, via Wikipedia Commons >

A few weeks ago I happened to be channel hopping and watched a panel discussion monitored by Joni Balter of The Seattle Times at a meeting of the Seattle City Club. The panel consisted of two members of the state legislature, a member of the governor’s staff, and a consultant for the Republican party. All seemed to be smart and informed people. The topic was the State of the State and how can we pull the state out of this economic recession and if so how long will it take, and what do we have to do to make it happen.

It was an interesting discussion but what amazed me as I sat and listened was that not one time did I hear the word “cities” come up in the discussion. (This is also true of the two candidates running for governor in their opening speeches.)

It continues to confound me that the leaders in Olympia don’t understand that healthy cities are the cornerstone of a economically healthy state. Seventy percent of our population live in cities. Cities are where the jobs are. Cities are where we educate most of our children. Cities are where we find most of the social networks that support our elderly, our poor, and our most disadvantaged. Cities generate most of the property, sales, and B&O tax that supports our state budget.

Yet when you see one of the governor’s finance people give a budget presentation, the various charts never point out the impact of cities on the state economy. Our economy is not driven by state government; it is driven by local government, cities, towns, and counties. This idea would seem obvious, but trust me it isn’t.

Having served as the mayor of two cities in the state, Bellevue and Bremerton, I have always been amazed at how little the legislature and the governor’s office understand the economic dynamic between the cities and the state, and how hard cities have to fight to be heard in Olympia. Most local governments end up having to hire their own lobbyist to give them a foot in the door to support legislation that helps cities and to stop legislation that hinders cities’ ability to grow their economy and support their citizen population.

The simple truth is that when cities win, the state wins.

So what needs to be done to help our cities, and therefore our state’s economy? Cities need the legislative tools from the state to create jobs, pave streets, and educate our kids. Cities have fought for tax-increment financing for years but have not prevailed. Since the demise of the car-tab fee, cities have not had the funds to rebuild their streets, so now every city in this state has a deteriorating street system. City councils have been given a car-tab fee authority but most have not had the political courage to increase the local car tab by even $20 a year.

Our state’s schools are now ranked below most of the other states in this country, and we should all be embarrassed and treat it as the number one priority for both our cities and our state.

I firmly believe the goal of the next governor and the legislature in the coming years should be the re-birth of Washington’s cities.

>>>

Cary Bozeman, currently CEO of the Port of Bremerton, has served as mayor of Bellevue and Bremerton.

< Note: This post originally appeared in The Stranger >

I’m asleep and dreaming in my bedroom in Columbia City. I’m in a bank. I’m waiting to make a mortgage payment. I have only a few minutes to make this payment before the bank charges a late fee. But the line is so slow. Three people are ahead of me, and all of the tellers are stuck with clients who have mountains of banking issues. The clock keeps ticking. My heart is beating hard. Moments from now, the bank will charge me $50. I’m about to scream. Suddenly, the main doors open automatically and the robot R2-D2 glides into the bank, stops beside me, looks at me with its single blue eye, and begins speaking to me in a language composed of electronic beeps/tweets—a high beep, a low tweet, a long beep, a strained tweet, a burpy beep, a whistley tweet.

What in the world does R2-D2 want from me? Who here can make sense of its bizarre beeping/tweeting? Where is C-3PO when you need him? He understands this droidian language; indeed, he can translate it into the Queen’s English. But there’s no C-3PO around, and R2-D2 is becoming agitated. Its metal head is twirling. It’s wheeling and whirring backward and forward. Its beeping and tweeting is getting faster and faster, louder and louder. I wake up. The time: 4:30 a.m. The season: summer. The sun: soon to rise. The sounds: the loud beeping/tweeting/chirping of the early birds of Columbia City.

The singing comes from the dawn-blue trees and always begins with one bird at around 4:00 a.m. By 4:30 a.m., that number rises to 20 or so birds. By 5:00 a.m., crows are contributing their horrible cawing to the growing cacophony. At 5:30 a.m., the bells of the light rail train on Martin Luther King Jr. Way South chime. At 6:00 a.m. comes the drone of planes flying over Beacon Hill. At around 6:30 a.m., the sound of traffic on Rainier Avenue begins to increase and blend with the birdsong. At 7:00 a.m., the sun is fully in the sky and the birdsong is less concentrated and more spread out—spatially and temporally. By 8:00 a.m., this part of the world sounds just about normal. But if it happens to be a Sunday morning, you’ll hear the songs from Luz Del Mundo (Light of the World) Church on Rainier Avenue. The church is small and packed with Mexicans—mothers, fathers, children, babies. Their Spanish spirituals rise up to my street like a bright cloud on a dark hillside. These people are close to God, but a long way from home.

All sorts of languages can be heard around here at all times of the day. Vietnamese flows fluently out of the house that’s next to mine. Next to that house, there’s the relentless language of a marriage on the rocks. The husband, a white male, is stuck with a wife, a white female, who, judging by the terrific intensity of his fury, has killed and eaten all of their children. Seriously, he is that loud and mad. One would be shocked to learn that a normal matter like infidelity triggered his explosions of yelling and cursing. Indeed, the house across the street opens all of its windows and blasts opera music at the house with the shouting man. The drama of an opera singer confronts the drama of a crazy husband. Occasionally, a pimped-out SUV separates the two dramas with crunk beats that boom so hard that the car’s metal rattles.

The languages in this part of Seattle range from human to inhuman. I heard one of the inhuman languages while on the number 7 bus. It happened at 10:00 a.m., shortly after I boarded the bus at the stop across the street from the Columbia Funeral Home. The bus, as usual, was late and slow. The bus, as usual, was packed with every race you could imagine. At the next stop, which is just down the road from Luz Del Mundo and just up the road from the Darigold milk plant, there was a disruption. A person, a drunkish middle-aged black American man at the back of the bus, began yelling at the driver in the front of the bus to open the back doors. The driver, a black American woman, was trying to open the doors, but they were jammed for some reason. The doors would begin to open, jam, and abruptly close. The rider would yell for the driver to do her job and open the damn doors. The driver would try to do her job, but the doors would not do as they were supposed to.

Two young white women were sitting right next to this commotion. They were clearly nervous about the rider’s escalating anger. They knew this was just the tip of an iceberg. The angry rider looked like his life had been hard. Maybe a few years of it were spent in prison. Maybe he was late for an appointment with a parole officer. Maybe a gang wanted his head. Maybe he was the last hired and the first fired. Maybe it was one of dem days. It’s possible the bill collectors were calling his home. Or his car had been repossessed, which is why he was on the bus in the first place. You see two terrified and defenseless white Americans and an angry black American, and your mind can’t help but fly back to the beginning: the dark days of the plantation, the Jim Crow laws, the 40 acres and a mule that never materialized, the low-tech lynching, the lack of fathers, reparations, opportunities—there’s a lot going on here. Don’t push him; he might be very close to the edge.

The white girls really wanted the doors to open and release this dangerous pressure from the bus. The driver tried again and failed again. Finally, a big and bald black man wearing dungarees walked to the doors, examined them, spotted the problem—a stuck soda pop can—and removed it. The doors then cleanly opened, the commotion was released out into the streets, order was restored. As the hero of the moment returned to his seat, the young white women thanked him with big smiles, bright eyes, and kind words. In their minds, they owed their lives to his calm and rational intervention. The big and bald black man stopped, looked at the young white women, and… began barking. It sounded exactly like a dog’s bark. Nothing about it was human. This man spoke dog. If you hadn’t seen it was a man, you would’ve thought it was a dog. The white girls were not frightened or upset but simply dumbfounded. Where in the world were they? How could this be happening to them? The black man stopped his barking, returned to his seat, and was silent for the rest of the journey down Rainier Avenue.

< THE DARIGOLD PLANT A dead rat nearby died dreaming of milk; photo by Rob Devor >

Not far from where this barking erupted, Andover and Rainier, I recently came across a dead rat next to the sidewalk. What amazed me about the dead rat was its location—right next to the huge Darigold milk plant. Made of the stuff of Speedy Gonzales, the rat was clearly thinking big. Instead of invading ordinary homes across the street, it was going to the source, the plant with its vats of cow’s milk. If the rat had made it inside—I think the attempt was made at night (I came across the rat around 9:00 a.m.)—it would have spent the evening drinking and swimming in heaven.

Two other impressive things about this little death. One, it happened right next to a mural that celebrates the diversity of Columbia City. The mural has everybody in it: a mariachi band, a jazz trumpeter, a deranged Arab, a white man holding a raccoon, a blond woman holding flowers, a melancholy East Indian woman, a Filipino woman who is laughing wickedly, a dragon, and, above this confusion of races, Chief Seattle trying his best to embrace it all with open arms. When the white man came to the land of his ancestors, the chief had no idea he was bringing with him the whole fucking world.

< CHIEF SEATTLE IS TRYING HIS BEST He didn’t know the white man was bringing with him the whole fucking world; photo by Rob Devor >

Two: As I approached the rat, walking just ahead of me were Somalian immigrants—a mother, three boys, and two girls. The mother (brown scarf on the head, black dress flowing over the body) was walking slowly. There was no rush, no worries, “hakuna matata.” Neither she nor the kids noticed the dead rat; or maybe they did and, my god, what did it matter—they’ve seen war, rape, murder, mass madness, famine, every kind of human deprivation. This is just a dead rat. This is another day in paradise.

What fascinated me about the Somalian family’s slow walk beside the tall wall of the plant—and this has nothing to do with the rat—is the central role that milk plays in the rural culture of their war-torn country. Milk, and particularly camel’s milk, is a matter of life and death. It and its by-products (butter, yogurt) are at times all that keep you from slipping into darkness. Indeed, the traditional Somalian greeting “Ma nabad baa?” (“Is there peace?”) is returned in this lovely way: “Nabad iyo caano” (“Peace and milk”).

Across from the Darigold milk plant are rows of homes and huge trees. One of the homes is abandoned, another should be abandoned, and another is ultramodern. One is receding into the woods, one is barely alive, another is rushing into the future. Columbia City not only has a mix of races, languages, cultures, and smells (particularly at dinnertime), but also architecture and spaces. Little here is uniform. One thing stands next to something that is completely different from it.

Take the Columbia City light rail station, for instance. The place has almost no coherence. First, there’s a towering forest just west of it—giant trees looming over small homes. There’s no calm here, no oneness with nature. Instead, there’s incredible tension between the humans and the trees, each of which could fall and crush to pieces a number of these brave houses and the church, Temple of Christ. The forest covers a huge area. It rises up to near the top of Beacon Hill and stretches all the way down to Mount Baker Station, claiming along the way a number of abandoned homes and losing ground here and there to development. It is thick and alive with birds and rats. I once saw a whole tribe of rats rushing up and down one of its trees. I noticed the rats because I noticed a cat in someone’s backyard staring intently at the jungle. I looked and saw what it saw—gray lives in the green leaves.

< EXTRATERRESTRIAL SHOVEL There is no resistance here to new and strange things; photo by Rob Devor >

Then there is the art at Columbia City’s light rail station: the huge hoe (you know?), the row of black/yellow electric poles topped with blue cones whose tips curve like a dragon’s tooth or a witch’s fingernail. There are also metal baskets that glow in different colors at dusk, three flutes lustfully twisted in some sort musical ménage à trois, and huge flyswatters (at least that’s what they appear to represent) that rest on beds of bushes. All of this is quite mad and only possible because this part of Seattle is a social, cultural, global laboratory. It is a place where new identities, ideas, and modes are being tested, where things have yet to be settled and, indeed, may never be settled. This is the open city. It’s also a city with much less political resistance to new and strange things. It is no surprise that South Seattle has light rail before any other part of Seattle. Much of North Seattle wants nothing to do with new things. North Seattle is a stable and uniform place. It clings to the past. Its future wants to be exactly like its past. It is not a laboratory.

Not so long ago, after dreaming and hearing the birds and descending planes, I woke up, showered, dressed, caught the 48—the “fortylate”—and almost arrived late at the studio for KUOW. I was here in North Seattle to talk about gentrification in South Seattle. The other guests that morning were former mayor Norm Rice, Richard Morrill, and Eric de Place. Even after all of this time, we are still trying to make sense of gentrification, an urban process that has its birthplace in Haussmann’s Paris. At that time, the middle of the 19th century, the process was about uprooting poor Europeans from their traditional neighborhoods. In 21st-century America, it is about uprooting poor black people. In Seattle, the process has pushed them deeper and deeper south.

The process is also about middle-class white people who have not seen their real income increase since the 1970s and have only homeownership as a way to make any real gains. To go into these poor and long-neglected neighborhoods, to take the risk, to improve the streets and economy, this is practically the only chance they have of making real money. The north is stable, and therefore the home prices are stable. In a neighborhood like Columbia City, anything can happen. Leaps can be made. To make the big bucks, you have to go where no one else will go.

Gentrification, of course, homogenizes streets and businesses. This has indeed happened in some parts of Columbia City, but not in others. So far, instead of homogenizing the whole neighborhood, gentrification has added new layers, new elements to the preexisting mix. Columbia City was a white neighborhood until fairly recently, the early 1970s. The Boeing recession resulted in white flight. Black Americans replaced the white Americans. In the 1990s, immigrants began flowing into the area. By 2000, 41 percent of the people living here were foreign-born. In the early 2000s, white Americans began their return. (The geographer Gary Simonson writes a short but informative analysis of 21st-century Columbia City called “Gentrification and the ‘Stayers’ of Columbia City” in the new book Seattle Geographies.)

Now there is a hyper-mixture of races, colors, statuses, attitudes, sizes, dreams, lovers. No one group is above the rest. Each is inside and interlocked with others. This year, the Census Bureau called Columbia City “the most diverse zip code in the country.” In 2008, it calculated that by 2042, the entire country will be like this—minority majority. You either live in this city now or will live in such a city in the future.